Last month, the Center for Migration Studies (CMS) published a study by Donald Kerwin that explores whether admitting refugees into the United States advances American foreign policy and strengthens our economy here at home. Kerwin compared refugees who arrived in 9-year ranges —1987 to 1996, 1997 to 2006, and 2007 to 2016 — and reported that most of the time, refugees in the United States perform better than the general population in America. He also argues that refugee resettlement provides the United States a unique soft-power advantage in international relations that improves safety and security.

The CMS report comes as the Trump administration continues to dismantle the U.S. refugee resettlement apparatus, despite growing evidence that refugees successfully assimilate into American life, contribute to our economy, and play an important role in our foreign policy.

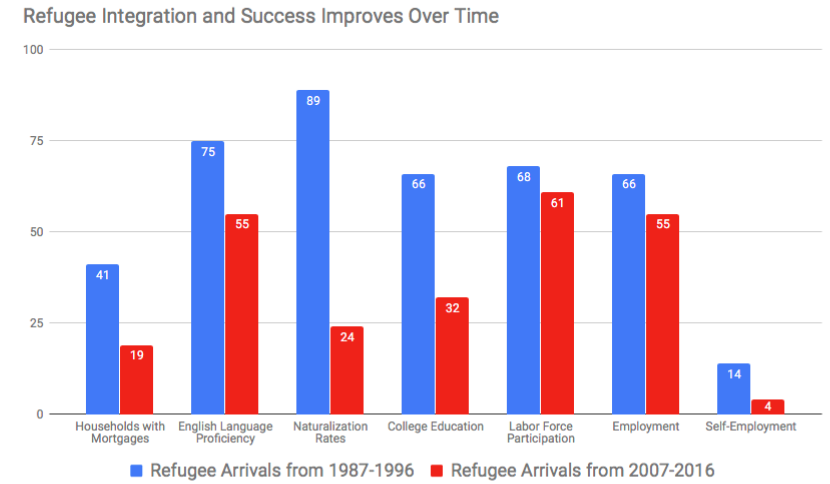

According to the study, refugee integration and success improves over time. Comparing the cohort of refugees with the most time spent in the United States versus the cohort with the least amount of time here reveals significant improvement on a range of metrics, as reflected in the chart below.

The proportion of homebuyers with mortgages more than doubles, naturalization rates triple, and the percentage of individuals obtaining a college education doubles, in addition to gains in language proficiency and overall employment.

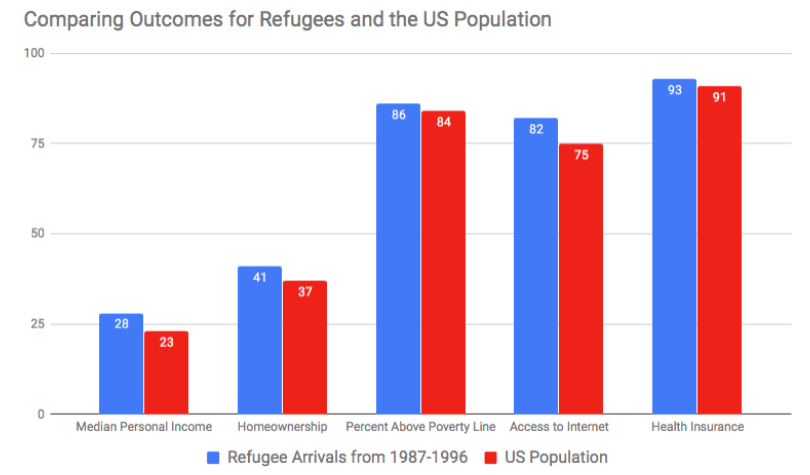

As documented in the chart above, refugee integration is so robust that it’s common for refugees to not just integrate into American society, but to perform better than the general U.S. population on important economic indicators like income and poverty rates.

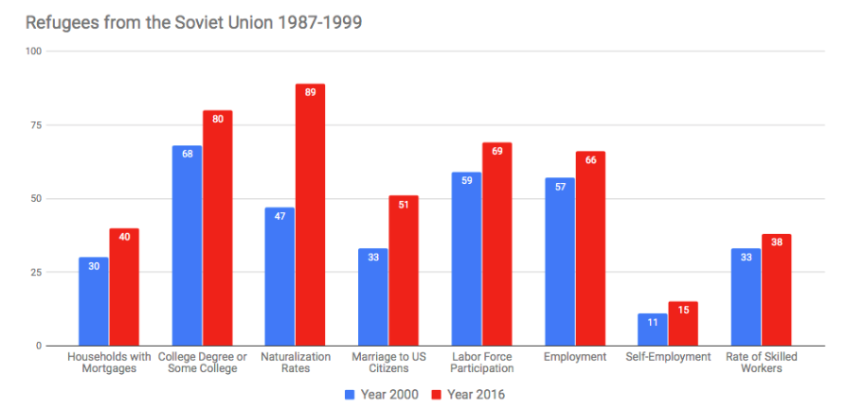

One specific cohort of refugees — those arriving from the Soviet Union between 1987 and 1999 — experienced remarkable economic and social gains, measured in 2000 and again in 2016. This refugee group saw median household income increase from $31,000 to $53,000 and personal income triple from $10,700 to $31,000.

The findings in this study bolster the argument that refugees are enthusiastically integrating into America, strengthening the case made by others. For example, in 2016, a survey of refugees in Colorado found after four years in the United States, 75 percent were “highly integrated.” Also in 2016, a report looking at 500,000 Somali, Burmese, Hmong, and Bosnian refugees found that after a decade, they were similar in social and economic circumstances as native-born Americans; refugee children were virtually indistinguishable from natives.

Kerwin doesn’t simply argue refugees integrate successfully and contribute domestically, he also outlines why refugee protection helps promote U.S. national security goals.

Kerwin points to an amicus brief to the Supreme Court in the travel ban case in which 51 of the nation’s top national security and foreign policy experts — many with years of experience at the highest levels of the U.S. government — argued the travel ban would harm national security. They noted that the component of the travel ban that halted all refugee admissions for 120 days would have the effect of “discouraging future assistance and cooperation … from military allies and partners” and “jeopardize the safety and effectiveness of our troops.” Their comments apply just as well to the administration’s larger attacks on the refugee system.

Refugee resettlement aids in the recruitment of assistance and intelligence assets abroad. For example, tens of thousands of locals in Iraq and Afghanistan risked their lives to support American forces in recent years. The U.S. military promised them and their families refuge for cooperating. However, years-long delays and lack of support in Congress have left thousands stranded where they are vulnerable.

Failing to live up to our promises to these individuals will impede our ability to recruit locals in future conflicts as it suggests our word cannot be trusted. Intelligence operations are built upon recruiting and developing local partners with on-the-ground knowledge, and eroding that ability undermines the United States overseas.

Kerwin also explains that “large-scale, chaotic migration poses a challenge to refugee integration.” Such irregular migration presents challenges for host countries that deal with the surge of refugees — such as European countries during the Syrian exodus. The strain felt by these countries can lead to dangerous populist political movements, integration difficulties leading to worse outcomes for refugees, and the likelihood for crime and terrorism to increase as time in refugee camps or urban centers lengthens without durable solutions.

The United States has historically resettled refugees to fight these challenges. The State Department has identified instances where targeted U.S. refugee resettlement has minimized tensions. A department report explains how “in certain locations, the prompt resettlement of politically sensitive cases has helped defuse regional tensions,” which meets U.S. goals. Stable countries are simply safer countries.

“Refugees embody and serve as living reminders of the ideals of freedom, endurance, hard-work, and self-sacrifice,” Kerwin writes, adding that the presence of refugees “closes the gap between the nation’s ideals and practices.” He’s right, and supporting victims of the enemies and ideologies we detest gives us credibility in undermining their regimes.

As I have argued before, advancing the national interest and ensuring robust refugee protection are mutually reinforcing — not exclusive — goals. The U.S. refugee resettlement program saves the lives of persecuted and vulnerable people, helps us recruit allies, reduces possible regional tensions that could otherwise escalate, and is a living manifestation of our ideals. American soft power abroad is bolstered by our refugee resettlement operations.

The dangerous caricature of refugees as drains on our economy and our society is simple untrue. Refugees do take time to get back on their feet following harrowing experiences, but they integrate quickly into American society and succeed, according to an assortment of metrics. Refugee resettlement saves lives while providing opportunity to those who contribute to our economy and help us achieve national security goals. The soft-power advantage we receive via refugee resettlement continues to be a crucial component of our foreign policy toolkit.