An improving understanding of global sea level rise is one of the current themes of 2016 climate research. My colleague Joseph Majkut recently reported that a new three-millennia sea level reconstruction demonstrates that the rate of sea level rise (SLR) in the 20th century was the fastest of the previous 27 centuries, and that human activities had a significant and (most likely) leading influence in that rise. In the last month, a couple of additional papers have expanded upon the human effects on sea level and what emissions over the next few decades mean for the next millennia.

Slangen et al. (2016) distinguishes between the natural and anthropogenic contribution to SLR from 1900-2005. The major finding of the paper is that 37 ± 38% of SLR from 1900-2005 is attributable to human influences (matching a qualitatively similar result [>45%] for the 1900-2011 period from Dangendorf et al. 2015). This number rises to 69±31% for the 1970-2005 period. As such, the human influence on SLR has increased with time and become the dominant driver in the last 45-years.

In contrast to analysis like this, climate skeptics often forward the idea that much of recent SLR is natural, part of a recovery from the little ice age. There is some merit to that statement. Slangen et al. calculate that, for 1900-2005, 38±12% of measured SLR is attributable to natural factors, the same as that from anthropogenic forcing for the 20th century. At the start of the 20th century, glaciers were melting because the world had warmed out from the Little Ice Age starting in the 19th century. It takes time for SLR to fully respond to such natural variations, because glaciers take decades or centuries to equilibrate with a new climate.

But what research like this Slangen et al. paper shows—and skeptics miss—is that the human influence grows with time. The total natural contribution could only explain 9±18% of SLR for 1970-2005, compared to 69±31% from anthropogenic influence. Whilst anthropogenic and natural forcing were about equally important during the first half of the 20th century, the influence of natural variability in influencing the long-term trend of SLR has diminished and anthropogenic forcing is dominating.

Interestingly in the study, there was very little contribution from melting ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica, which represents a potential source of rapid SLR. But as anthropogenic influence continues to dominate throughout the 21st century and beyond, thermal expansion and glacier contribution will continue to add to SLR in addition to the potential contribution from the ice sheets.

Clark et al. (2016) explores the consequences of 21st century climate policy on global SLR. They argue human climate influence, which generally accounts for changes between the industrial revolution until the end of the 21st century (the 250-year 1850-2100 period) is better placed within the context of the past 20 millennia – when the planet emerged from the ice age and humans evolved – and the future 10 millennia.

The long time horizon is important because the policy decisions made in the coming decades will have a lasting effect (irreversible on millennial time-scales) on the climate system. The reason the actions of humans over the next decades are crucial is because of the commitment made due to the long residence time of CO2 in the atmosphere (and subsequently – persistence of elevated temperatures and sea levels). Clark et al. explain:

20–50% of the airborne fraction of anthropogenic CO2 emissions released within the next 100 years remains in the atmosphere at the year 3000, 60–70% of the maximum surface temperature anomaly and nearly 100% of the sea-level rise from any given emission scenario remains 10,000 years, and the ultimate return to pre-industrial CO2 concentrations will not occur for hundreds of thousands of years. If CO2 emissions continue unchecked, the CO2 released during this century will commit Earth and its residents to an entirely new climate regime.

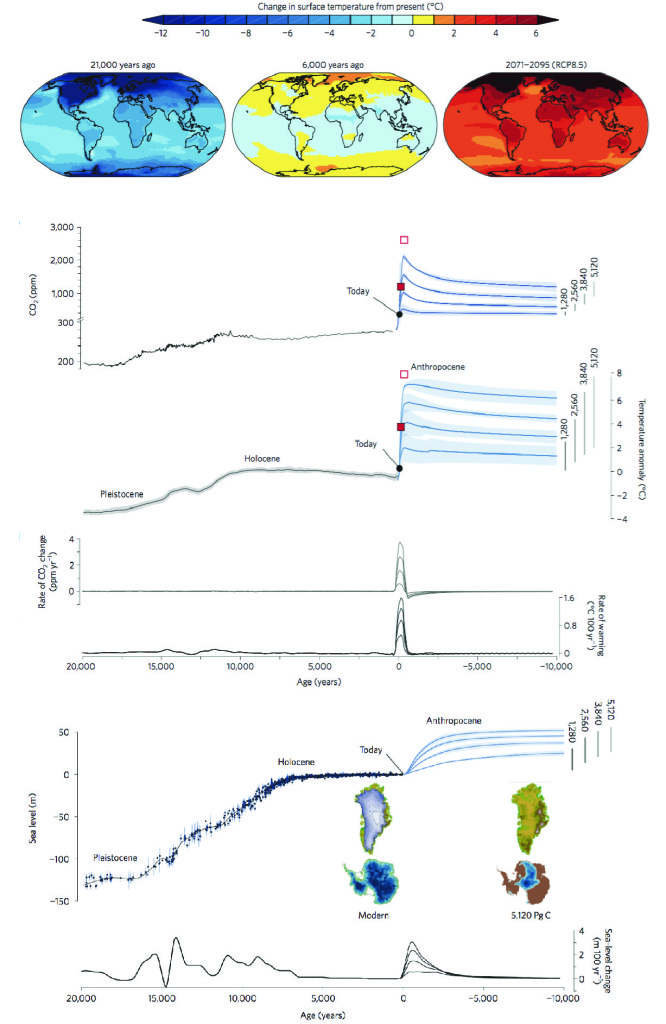

This is illustrated by Figure 1 below, which combines the first two figures in the Clark et al. paper. Using paleo data for the past and model predictions for the future, it shows the effect of anthropogenic emissions on the climate could last 10,000 years.

Figure 1: (From Clark et al. 2016) The previous 20 and future 10 millennia of climate changes. Data are from paleo-records (past) and model output (future).

The climate commitment keeps temperatures elevated and melts the great ice sheets over thousands of years. How much they eventually melt depends on future cumulative emissions of greenhouse gases. The low emission scenario in Clark et al. keeps warming around 2 °C, and total SLR in the region of 25m (after 10,000 years), whereas a high emission scenario suggests a potential SLR above 50m. The high minus low emission scenarios difference represents a doubling in future global SLR, making choices about emissions in the coming decades critical for the eventual rise.

These papers demonstrate two important results from climate science regarding sea level rise. The first is that much of the recent change observed in global sea level is due to human influence and that influence is increasing in importance for global sea level changes. The second is that greenhouse gas emissions are in a position to permanently (on known human timescales) alter the climate, and that will have lasting effects on sea level. Emissions over the next century plausibly lead to very different future states of the world.

Image by 4311868 on Pixabay Stock.