Republican reformers have repeatedly promised affordable healthcare for all Americans — doubly affordable, in fact. They promise sufficient subsidies to put premiums and out-of-pocket costs within reach of low- and middle-income consumers. At the same time, they promise that the plan will be affordable to the federal budget, even given the constraints their most conservative members would like to impose on federal spending.

Unfortunately, the American Health Care Act (AHCA) now before Congress will make healthcare affordable in the budgetary sense only, by making it less affordable in the individual sense. According to analysis by the Congressional Budget Office, the AHCA will reduce the budget deficit by $337 billion over a ten-year period, but only at the expense of reducing the number of insured by 14 million in the near term and by 24 million after the full effects of the bill come into force. As the CBO points out, even many people who retain coverage will find it more expensive because the ACHA tax credits will be less than the subsidies available through exchanges under the current Affordable Care Act (ACA). For others, the only option that will become more “affordable” is that of going without insurance, due to the ACHA’s elimination of the ACA’s individual mandate.

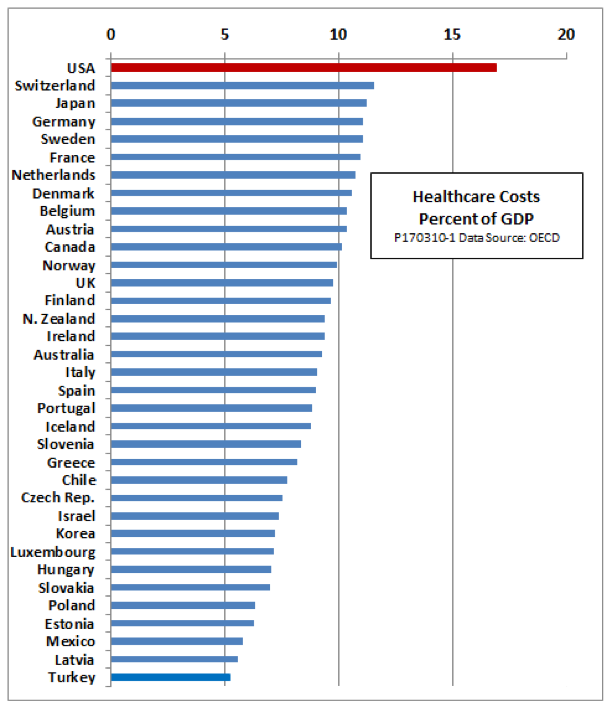

Under the ACHA or ACA, one uncomfortable fact remains unavoidable: There is no way to make healthcare affordable for either the budget or individuals without strong action to control prices for drugs, medical devices, hospitals, and doctors’ fees that are higher than in any other country. The current draft of the ACHA does nothing to deal with that critical problem.

The elephant in the room

Princeton economist Uwe Reinhardt calls high healthcare prices the “elephant in the room.” Yes, he says, there is waste at every level of the U.S. healthcare system. Yes, U.S. doctors and hospitals probably do overuse some procedures (C-sections) and tests (MRIs). Still, Reinhardt argues that by and large, it is the high price of care, not an excessive amount of care, that makes our healthcare so much more costly than that of any other advanced country. We don’t have more hospital beds per capita, or more doctors, or more births. We just pay more for each unit of service.

Reinhardt cites data from the International Federation of Healthcare Plans to back up his claim. For example, in 2012, the average cost of an appendectomy in the United States was $13,851, compared to $5,467 in Australia, the country with the next highest price. For a normal delivery, the U.S. price was $9,775 compared to $6,846 in Australia. The range of prices charged within the United States was even more astonishing than the average. At the twenty-fifth price percentile, an appendectomy in the United States cost $8,156 — higher than Australia’s average. At the ninety-fifth percentile, the U.S. price was an astounding $29,426. A normal delivery in the United States raged from $7,282 to $16,653.

What causes high prices and what can we do about them? Here is a list of some of the most common ideas. (Warning: Each of the following paragraphs would have to be expanded to its own long post — or even to a doctoral dissertation — for a complete treatment.)

Lack of transparency

A lack of transparency helps keep prices high by discouraging consumers from shopping around for the best deal, even when their problem is not so acute that they have no time to shop. As Reinhardt puts it, “Fees in the private [healthcare] sector have been jealously guarded trade secrets among insurers and providers of health care.”

Some reformers hope to encourage consumers to be smart comparison shoppers by imposing higher deductibles and copays and softening the blow with health savings accounts, which consumers can draw on to pay their out-of-pocket costs. However, those devices are useless if consumers cannot get price information in the first place.

Some insurers are trying to combat the lack of transparency by providing comparative price information, but what they give is not always easy to understand, and many patients do not look at it. A 2015 poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 6 percent of patients had seen price information on hospitals and doctors, and only 2 to 3 percent had made use of it.

There are plenty of ideas around to make price information more accessible and easier to use. For example, Jeffrey Kullgren, writing for the New England Journal of Medicine Catalyst, recommends bundling price quotes to show the sum of all fees that a consumer would face for a procedure, rather than separate fees for use of facilities, doctors’ services, supplies, and medications. He also recommends that providers have dedicated staff to provide price information to patients and explain what it means. Providers should also be willing to tell patients what services might not benefit them. For example, a $100 blood test might be essential for one patient but provide no useful information to another.

Structural incentives

Even when price information is available to consumers, the structure of their insurance plan may not encourage them to use it. For example, if a plan covers whatever the provider charges, once a deductible has been satisfied, the consumer has no incentive to look for the best value for major procedures. In another article, Reinhardt recommends “reference pricing,” a scheme under which an insurer pays only the price charged by a low-price provider in the area, leaving consumers to pay the balance if they choose a higher cost provider.

Narrow network policies are a step in that direction of reference pricing, but they can meet resistance when patients have established relations with certain doctors and hospitals. Also, some consumers, to their sorrow, find that narrow networks can fail, leaving them with surprise bills from radiologists or anesthesiologists who are not network members, even though the hospitals where they work are.

Individual consumers are not always the ones to blame for a failure to respond to incentives. Reinhardt notes that employers are also notoriously bad shoppers for low priced care. One reason may be that they think they can pass higher healthcare costs along to workers through lower wages — a hypothesis that many labor economists agree with.

At a minimum, it is fair to say that a well-structured healthcare system should include some checkpoint in the chain between provider and patient where some party has an incentive to ask whether the product or procedure in question has a medical value that is commensurate with its cost. There is room for discussion as to who this should be or what standards should apply. The problem with the current U.S. system is that often no one at all has an incentive to address this question.

Fragmentation

Insurance coverage in the United States is highly fragmented. In the private insurance market, there are many carriers. Small carriers, especially, have weak bargaining power compared to large hospital groups and drug companies. On the government side, coverage is divided among Medicaid, Medicare, and VA systems that have differing authority to negotiate for low prices — and sometimes none at all.

In the private sector, insurers could be given the power to negotiate jointly with providers in their area. Government providers could also have a way to negotiate jointly for advantageous prices.

The ultimate in bargaining power would be to have a single payer for all healthcare services. The bargaining power inherent in single-payer systems is one of the main reasons other advanced countries have lower healthcare costs and still manage to produce superior quality of care compared with the United States, where doctors remain in individual practices and hospitals are privately owned.

Drug prices

The issue of pricing has nowhere received more attention than in the case of drug prices. Some observers think the advent of a million dollar pill is not far off. A recent commentary by Scott Alexander provides a good summary of the complexity of the issues involved.

The central problem is that of balancing the high costs of research and testing against the relatively low costs of producing drugs, once they are in use. The current regime handles this by giving drug companies temporary monopoly rights through patents. During the patent period, producers can charge whatever prices they deem appropriate. After patents expire, competition from manufacturers of generics usually brings the price down toward production costs.

This regime can have good outcomes or bad. The new generation of drugs to fight hepatitis C, which are very expensive but also very effective, appear to represent the good end of the spectrum. Research that, at vast expense, only fiddles with a molecule or two to produce a drug that prolongs a patent with no added medical benefit is the bad end.

Price discrimination also contributes to high U.S. drug prices. A 2015 report from Bloomberg found that the prices of seven out of eight common medications cost less abroad than in the United States, even after taking into account the discounts negotiated behind closed doors with some insurers. The cholesterol lowering pill Crestor cost five times more in the United States than in the next-most-expensive country at list price, and more than twice as much even after discounts. The leukemia drug Gleevec cost four times more in the United States, and no discount was available.

Economists do not universally condemn price discrimination. No one objects when theaters or theme parks charge reduced prices for children. Airlines use price discrimination to keep their airplanes filled — a practice that lowers average prices in the long run and increases the number of fights passengers can choose from. However, there are ways to keep price discrimination from getting out of control without undermining its usefulness in markets where fixed costs are high.

High barriers to resale across markets are one factor that facilitates price discrimination. For that reason, many reformers suggest allowing consumers to purchase drugs online from retailers in Canada, Mexico, and other countries where prices are lower. Since the United States is the high-price consumer in most cases, moves to reduce price discrimination would probably lower prices here. However, the net gains would be less than suggested by the current cross-border price differential, since curbing price discrimination would probably raise drug prices abroad at the same time it lowered them in the United States.

Mergers, monopolies, and entry barriers

Numerous studies (this one, for example) have found that mergers among hospitals tend to raise prices in the affected areas. Mergers between hospitals and physician groups can have a similar effect. During the Obama administration, the Federal Trade Commission began to push back against the wave of mergers. It is not yet clear whether such actions will continue under the Trump administration.

Entry barriers are another factor that contributes to a lack of competition and higher prices. A recent study from the Mercatus Center notes that thirty-six states do not allow the entry of new hospitals without a certificate of need issued by a government agency. The ostensible purpose is to improve the quality of care by preventing excessive competition. The Mercatus study casts doubt on that claim, showing that by some measures, the quality of medical service is actually lower in states with certificate of need laws.

Economists have also long argued that limits on admission to medical schools help to keep doctors’ salaries higher than in other equally wealthy countries. Observers on both the left and the right of the political spectrum complain that the American Medical Association acts as a cartel in resisting the expansion of medical schools even as the number of applicants rises.

Administrative costs

The fragmented nature of U.S. healthcare produces higher administrative costs than other countries. Those costs ultimately work their way into the prices of hospital care, physician services, drugs, and every other area of care. A study from the Commonwealth Fund found that in 2014, administrative costs accounted for 25 percent of all hospital expenses—higher than any of eight other countries studied, and double the level of Canada. An earlier study from the Office of Technology Assessment found similar results for total administrative costs in the healthcare system.

Single payer systems are inherently more efficient in terms of administrative costs. International experience shows that many savings can be realized within a unitary administrative framework without requiring that hospitals be owned and operated by the government or that all physicians become government employees.

No simple answer but a need for action

It should be clear from these examples that there is no single explanation for high U.S. healthcare prices, and no simple solution. Action is needed, but it needs to come across many fronts at once — against mergers, entry barriers, drug prices, lack of transparency, administrative fragmentation, and other problems. If each of these areas could eliminate a single percentage point of the gap between U.S. prices and those that prevail in our high-income peers, we could save billions of dollars a year.

If the current draft of the AHCA is not revised to address the problem of excessive healthcare prices, it is likely to do little to improve affordability. Any savings it brings can come only from reducing the quantity or quality of care provided, not by reducing costs per unit of service.

Paul Ryan, the most vocal backer of the bill, insists that this is only the first step. We have to understand, he says, that the AHCA is tailored to meet the arcane requirements of the Congressional reconciliation process, which limits changes to matters directly affecting taxes and spending. He promises a second wave of reforms to address cost controls and issues of efficiency.

There is a huge danger in this approach, however: Every dollar saved in healthcare costs means a dollar less of revenue for some healthcare provider. Any proposals to cut drug prices, increase competition among hospitals, or squeeze out administrative costs in the insurance industry will face tooth-and-nail opposition from an army of lobbyists.

The AHCA, if passed in its current form, will satisfy the potent symbolism of repealing Obamacare. Any Republican Senator or Congressman who votes against it will have broken an explicit campaign promise and will face a primary fight in the next election. But once a repeal bill passes — any bill — the political heat will be off. The motivation to tighten the screws on big pharma or the insurance industry, against the will of the lobbyists, will evaporate.

At the same time, Democrats will dig in their heels against anything that might make the AHCA work better. At least a few Democratic votes will be needed for any further reforms that can’t squeeze through the eye of the reconciliation needle. But where is the political motivation to cooperate? Many Democrats may well prefer to see a half-baked GOP reform collapse in a death spiral, (as I predicted in an earlier post that it will do), and hope to pick up the pieces after the 2020 elections.

In short, the two-part approach is unworkable. Sen. Tom Cotton was right when he tweeted to his colleagues in the House to “Pause, start over. Get it right.”