Republicans seem determined to shift responsibility for health care finance and policy toward the states. Some of the biggest changes will come in Medicaid. The Better Care Reconciliation Act (BCRA), pending in the Senate, sharply cuts federal spending, leaving states with the choice of increasing their own contributions to maintain current enrollments, or reducing coverage. Aside from Medicaid changes, the states gain the right to redefine the essential services insurance must cover, to experiment with high risk pools, and to change policies toward pre-existing conditions.

A group of GOP senators skeptical of the BCRA offered a different proposal that permits even greater diversity in state health care policy. The Patient Freedom Act – sponsored by Sens. Susan Collins (R-ME), Bill Cassidy, MD (R-LA), Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV) and Johnny Isakson (R-GA) – gives states three choices: keep the existing framework of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) with most of its federal subsidies, sign up for a new market-oriented system centered on direct contributions to health savings accounts for each individual, or design a new system of their own, with federal approval.

The decentralization is intended to bring an upsurge of innovation, leading to a more flexible, more customer-centered system that better meets the needs of the diverse populations of the country. As American Enterprise Institute (AEI) visiting scholar Joel Zinberg puts it, the BCRA “makes it far more likely that Obamacare’s section 1332 ‘innovation waivers’ can become effective tools for state-based experimentation and reforms to improve insurance coverage.” He notes that the BCRA will lift restrictions that inhibit waiver applications, streamline the application process, and create a $2 billion fund to motivate states to apply for innovation waivers.

For the sake of argument, let’s take the promised upside at face value. Even so, increased state-to-state diversity in health care policy and increased state responsibility for funding have their downsides. They will strain the resources of many states, undermine labor mobility, and weaken key macroeconomic stabilization mechanisms. These unintended consequences must be part of the health care debate.

Constraints on states’ ability to respond to changes in federal policy

Republicans insist that the BCRA will not actually cut Medicaid spending. Instead, they claim that states will step in to fill the gap as the growth of federal spending slows. Sen. Pat Toomey (R-PA), speaking on CBS’ Face the Nation, put it this way:

No one loses coverage. What we are going to do, gradually over seven years, is transition from the 90 percent federal share that Obamacare created and transition that to where the federal government is still paying a majority, but the states are kicking in their fair share, an amount equivalent to what they pay for all the other categories of eligibility.

The problem is that not all states have the capacity to respond constructively to the obligations and opportunities created by the BCRA. A new study from the Kaiser Family Foundation examines five groups of factors that affect states’ ability to respond to federal Medicaid cuts and caps:

- Medicaid policy choices, including expansion, eligibility, and reimbursement rates

- Demographics, including poverty rates, age, and urban-rural mix

- Health status of the state population, including disabilities, mental health problems, and opioid death rates

- Budget and revenue issues, including personal income, tax policies, and current levels of per capita spending

- Healthcare cost factors, including levels of per capita healthcare spending, insurance premiums, health shortage areas, and Medicaid provider participation.

All states face some problems in responding to the proposed changes in federal policy, and nearly two-thirds of them are seriously exposed to more than one risk factor. Eleven states rank in the top five for five or more risk factors (Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, South Carolina, Texas, and West Virginia). The study notes that states with multiple risk factors will face difficult choices making program cuts or filling gaps in federal funding without reducing the quality of care to some residents, and even greater problems in coping with future needs, new therapies, or adverse demographic changes.

As the Niskanen Center’s Samuel Hammond pointed out in a recent post, the evolution of Canada’s health care system provides some parallels. Canada’s system, too, is a joint federal-provincial program, with the federal government now covering 23 percent of costs. A 1977 reform changed the earlier subsidy formula to a block grant system, similar to one favored by Republicans in the U.S. Congress. Hammond’s conclusion is that some of the hoped-for benefits of provincial control did emerge, but those gains were tempered by a tendency of provinces to react to budget constraints by cutting services and reducing provider reimbursements. The latter reaction raises a particular red flag, since critics already complain that Medicaid reimbursement rates are too low.

In short, although the BCRA does not require states to cut Medicaid coverage, it seems likely that there will be cuts in many states. Even a sympathetic observer like Zinberg concedes it is “doubtful that innovation can offset decreased federal funds without cuts to Medicaid benefits and enrollment.”

Impacts on labor mobility

Labor mobility—the ability of people to change jobs to match their skills with the changing needs of employers—is a key to the efficiency of the labor market. Writing for Liberty Street Economics, Fatih Karahan and Darius Li maintain that

[T]he willingness of the U.S. workforce to move is a factor behind the greater dynamism of the U.S. labor market compared to Europe. While Europeans tend to be more reluctant to move to distant places within their respective countries, the idea of moving across state borders for a job has been woven into the fabric of the American Dream.

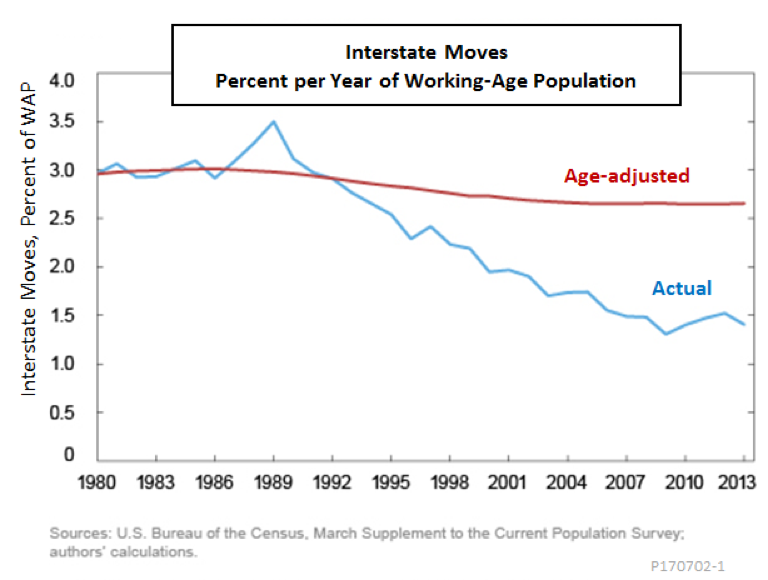

However, as Karahan and Li note, interstate mobility in the U.S. labor market has fallen substantially in recent decades. A part of the reduction is due to the aging work force, since older workers typically move less often. However, their calculations suggest only 20 percent of the decrease in mobility can be traced to demographic factors. The gap between the red line, which shows how much mobility was predicted to drop due to age-adjustment alone, and the blue line, which shows the actual mobility trend, must be due to something else.

Karahan and Li, along with other teams like one led by Raven Molloy of the Federal Reserve Board, have considered many possible causes of declining labor mobility, including indirect effects of demographic change, better employer-worker relations, greater wage equality, changes in job training policies and decreasing social trust. Despite their efforts, a large part of the decline in mobility remains unexplained.

Institutional changes must also be considered. Although the decline in labor mobility may have benign causes, such as better employer-worker relations, less benign causes are at work, too. There is a consensus that institutional changes that discourage interstate moves in search of better jobs reduce labor market efficiency.

Elsewhere, I have pointed to the rise in occupational licensing and job-lock caused by employer-sponsored health insurance as examples of this phenomenon. Increased state-to-state diversity in Medicaid and other healthcare programs will likely have similar effects. The greater the diversity, the greater the risk that a move to a new state results in a reduction in coverage or an increase in its cost. Even with adequate access to health care in the new state, a new resident might encounter gaps in coverage, waiting periods, or burdensome administrative requirements.

The problems of interstate moves already encountered under Medicaid illustrate the issues. The American Eldercare Research Organization characterizes transfers of Medicaid coverage from state to state as “difficult, but not impossible.” As the organization’s website explains,

Much to the surprise and dismay of many, Medicaid coverage and benefits cannot be simply switched from one state to another. While Medicaid is often thought of as a federal program, each state is given the flexibility to set their own eligibility requirements. Therefore, each state evaluates its applicants independently from each other state. Those wishing to transfer their coverage must re-apply for Medicaid in the new state. Further complicating matters is the fact that someone cannot be eligible for Medicaid in two states at the same time. Therefore, in order to apply for Medicaid in a new state, the individual must first close out their Medicaid.

You might think Medicaid would be irrelevant to anyone with good enough job prospects to make it worth moving to a new state, but that is not really true. Households with incomes well above the standard Medicaid cut-off can be affected if they have a special-needs child receiving community-based care under a Medicaid waiver. A similar situation faces workers with elderly relatives who receive community-based care that allows them to live at home.

Policies regarding waivers and community-based care already differ from state to state more than standard Medicare. MedicareWaiver.org explains the situation as follows:

The waiting period to get onto a waiver program can be many years, and varies by state. Unfortunately, waiver eligibility does not transfer from state to state. This is a huge problem for families who wish to move to another state. It also unfairly distributes the federally matched dollars among states because each state determines its own budget.

Giving states more flexibility in crafting health care policies exposes even more workers to similar barriers to interstate job moves. Subsequently, such policies suppress labor mobility and reduce market efficiency.

Macroeconomic consequences of healthcare federalism

The macroeconomics of business cycles might seem a long way from health care policy, but, as in the case of labor mobility, there is a connection. The connection lies in the unintended effects of health care decentralization on countercyclical fiscal policy.

Countercyclical policy is the use of tax cuts or spending increases as an economic stimulant during a recession, and the use of tax increases or spending cuts to hold the lid on during a boom. Sometimes that means using active stimulus measures, like the Bush administration’s tax cuts in the spring of 2008 or Obama’s stimulus package in early 2009. However, the federal budget contains powerful automatic stabilizers that work to smooth business cycles even when no active measures are taken.

The most important automatic stabilizers are decreases in personal and business taxes that occur when incomes fall during a recession, and increases in spending on unemployment compensation and other social benefits that occur when large numbers of people lose their jobs. Medicaid is one of those automatic stabilizers. A 2009 study from the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that an increase in the unemployment rate from its 2007 level of 4.6 percent to 10 percent adds more than 5 million people to the roles of Medicare and related children’s health programs.

Moving responsibility for Medicaid and other health programs from the federal to the state level, as Republican health care reforms propose, undermines Medicaid’s effectiveness as an automatic stabilizer. The reason is that state finances are subject to balanced budget rules. Except to the extent they are cushioned by rainy day funds, state expenditures on non-capital items are constrained by tax receipts. During a recession when tax revenues fall, expenditures must also be cut—fewer teachers in the schools, fewer rangers in the parks, and fewer home health assistants for the elderly and disabled. Such cuts are procyclical—they add momentum to an economic downturn, rather than moderating it.

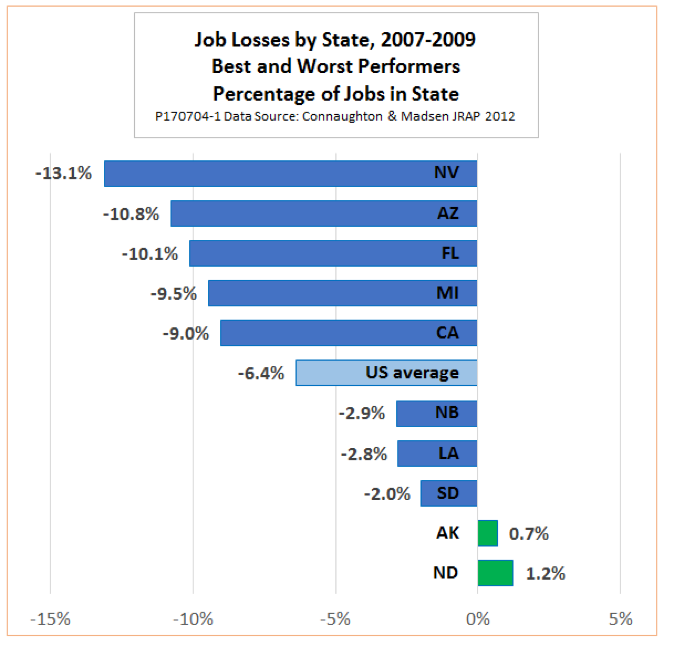

The problem of procyclical state spending is made worse by the fact that recessions always hit some states harder than others. For example, during the downturn of 2007 to 2009, job losses in Nevada were more than twice the U.S. average, with Arizona and Florida close behind. Meanwhile, Alaska and North Dakota actually gained jobs.

Does it really matter? Yes, as we can see by comparing the United States with the European Union (EU). Individual member states of the EU face balanced budget constraints, as do all 50 U.S. states. However, the central budget of the EU accounts for only two percent of all government spending, with member states and local governments responsible for the other 98 percent. In the United States, the ratio is about 70/30.

As a result, the problem of procyclical policy in member states is even worse. During the global financial crisis, the most affected states of the EU were forced to undertake harsh austerity programs that pushed unemployment rates up and kept them high for years. In the more fiscally centralized United States, the unemployment rate reached its peak and began to decline much earlier.

The decentralizations of health care policy embodied in the BCRA will not, by themselves, turn Nevada into Greece, nor will they drag U.S. macroeconomic performance down to the level of the EU. They will, however, be a clear step in the wrong direction.

The bottom line

Federalism has its place. Not all public policy decisions should be made in Washington. There are valid reasons to leave many areas of policy to the 50 states. The needs and preferences of individuals vary from one state to another, and states often act as laboratories to test innovations that later become more widely accepted practices. Health care policy is no exception.

However, decentralization of health care policy and finance also has a downside. In states that are less equipped to handle their newfound freedoms and responsibilities, we expect some people to experience a decrease in health care quality and access. Another unintended consequence of decentralization is a decrease in interstate mobility and a loss of labor market efficiency. Still another is a weakening of the automatic fiscal stabilizers that help the economy weather recessions, as well as an increase in the already wide degree to which the economic downturns affect individual states.

The law of unintended consequences operates in health care. Failing to acknowledge these consequences will not make them go away.

Edwin G. Dolan is an economist, educator and Senior Fellow at the Niskanen Center Senior Fellow. His prior pieces on the topic of health care reform include:

The Key Questions Any Obamacare Replacement Must Answer

Universal Catastrophic Coverage — Or How the Senate Can Fix the AHCA

Do High-Risk Pools Have a Future in Health Care Reform?

Universal Healthcare Access is Coming. Stop Fighting It and Start Figuring Out How to Make It Work

Healthcare Will Never be Affordable Without Action on Prices