For seven months, we’ve witnessed the GOP congressional leadership’s flailing attempts to pass legislation as if Democratic lawmakers don’t exist. In theory, this might seem to make sense. The Republicans, after all, have a majority in both houses. As long as they can use the reconciliation process to avoid Democratic filibusters in the Senate, negotiating legislative packages among themselves should provide an easier path for enacting their agenda than one which brings Democrats into the political conversation. With Democrats hell-bent on blocking Republican initiatives, bipartisanship would mean abandoning Republican dreams of total (or near-total) political victory.

The Obamacare “Repeal-and-Replace” effort, however, demonstrates that this is easier said than done. While pundits and politicos blame White House incompetence, distractions associated with the Russian electoral scandals, a lack of seriousness in crafting a governing agenda while the GOP was in the political wilderness, and ideologically charged intraparty factionalism, that’s only part of the story.

The bigger story is that the Ryan-McConnell strategy of partisan governance is a recipe for failure. It has rarely proven successful in the past, and there is no reason to believe that partisan governance will prove any easier to execute in the future.

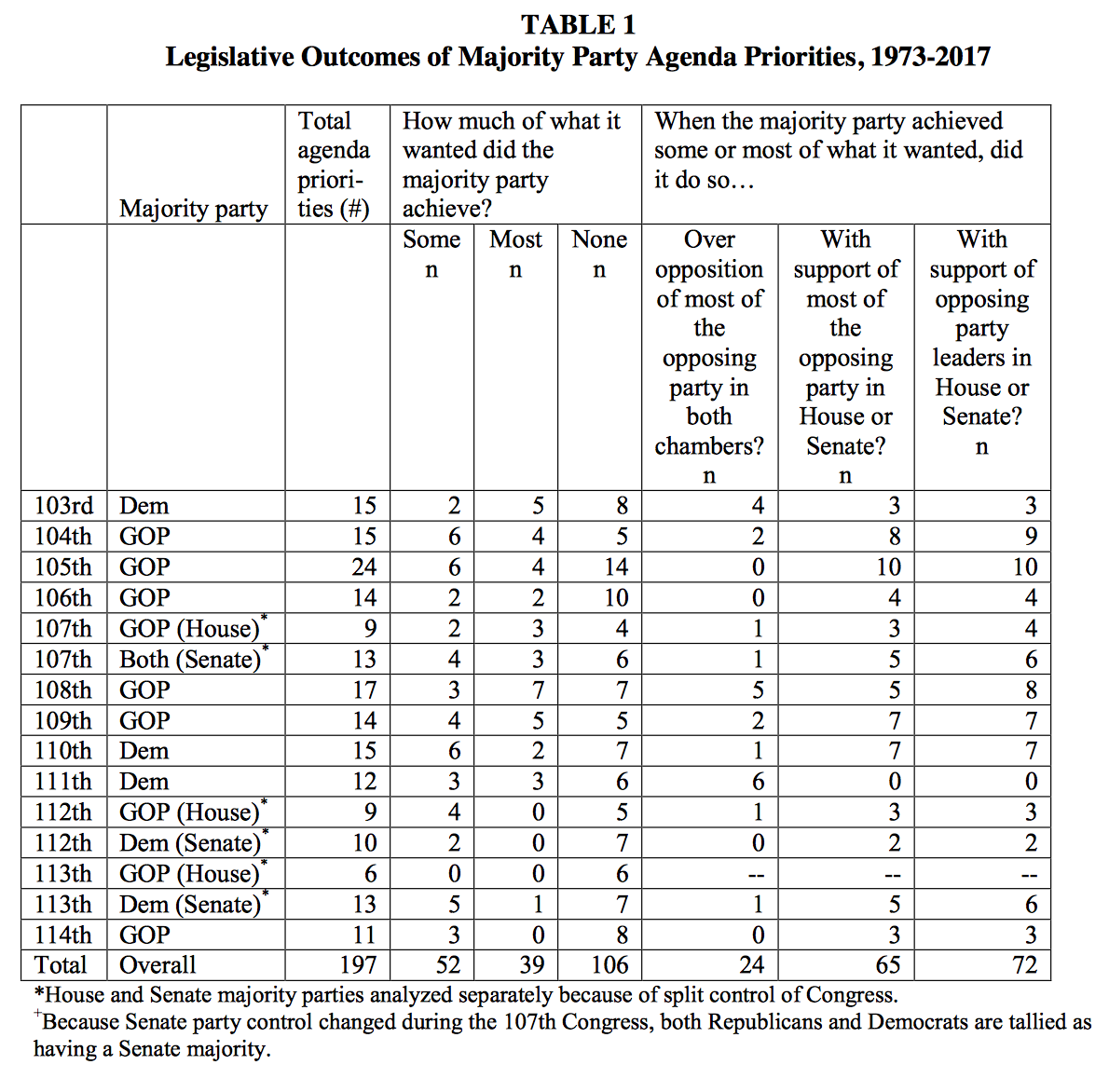

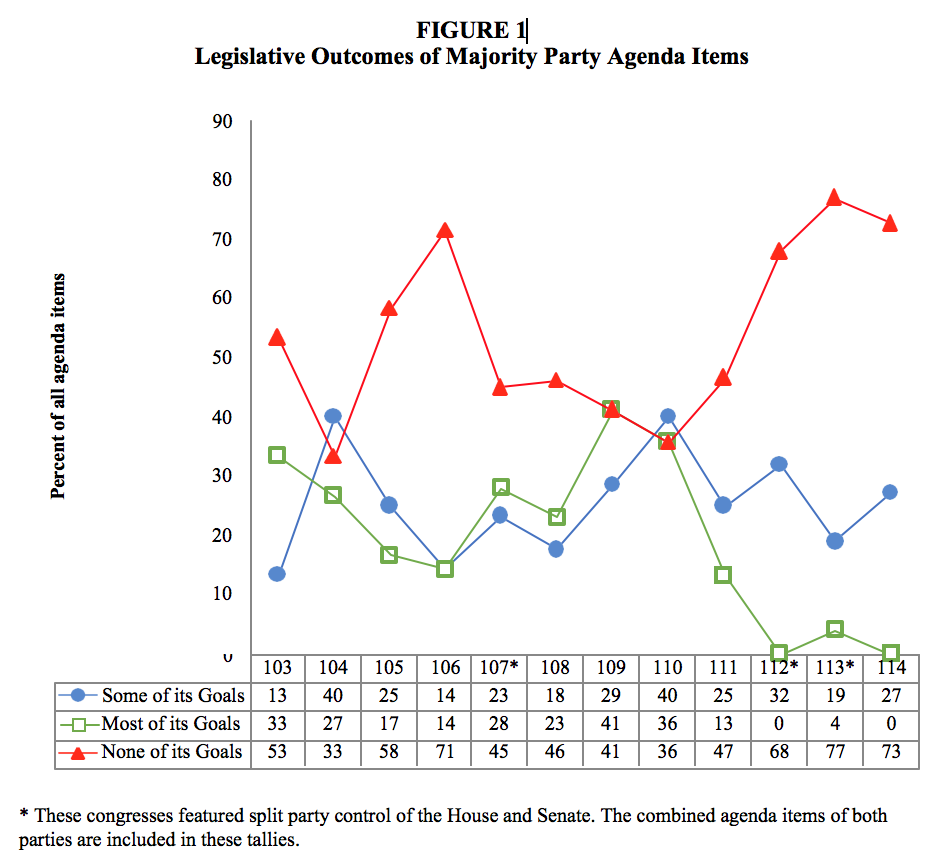

In a recent paper, political scientists James Curry and Francis Lee examined, in part, the ability of majority parties to pass their most important legislative priorities in each Congress from 1993-2017…and how much bipartisan support they typically needed to do so.

Below, the tale of the tape, in tabular form and then displayed over time:

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Table 1, p. 24.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Table 1, p. 24.

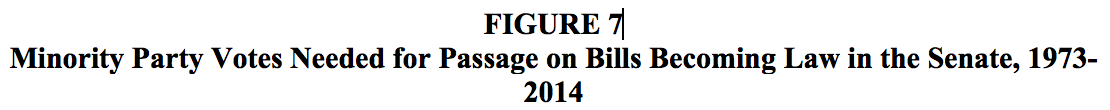

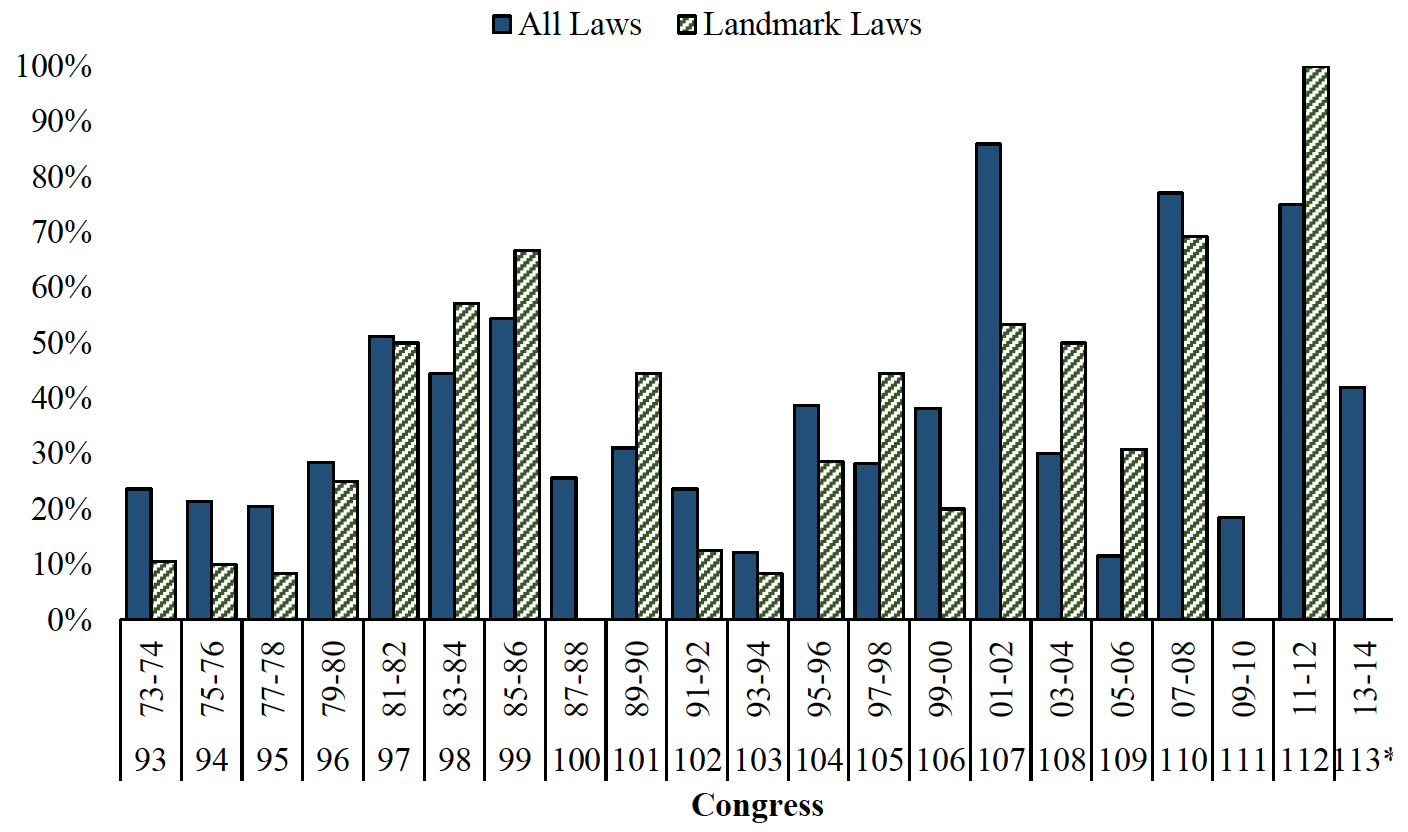

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 7, p. 25.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 7, p. 25.

Looking over the record of success on top legislative priorities over the entire time series, Curry & Lee find:

- Political majorities failed to advance anything 54% of the time.

- Even under unified government (i.e., when one party holds both houses of Congress and the White House), majorities failed to deliver anything 47% of the time.

- Majorities with unified government got some of what they wanted 21% of the time, and those with divided government got some of what they wanted 28% of the time.

- Only 18% of the time did political majorities advance legislation delivering most of what it promised.

- Majorities under unified government got most of what it wanted only 27% of the time.

- On only 10 occasions in the past 44 years [1] (5% of the time) did majorities get most of what they wanted over the opposition of the majority of the minority party, and without the endorsement of at least one elected party leader of the opposing party in either chamber. (Adding to that figure legislation that achieved only some of what they wanted brings the success rate up to 12%.) All but one of those 10 successes occurred during periods of unified government. The outlier—the PAYGO rules adopted in the 110th Congress—did not require a presidential signature.

If anything, however, the strategy being embraced by Paul Ryan is even harder now than in the past. More congressional seats are uncompetitive today than ever before. Convincing members from hyper-partisan districts to back a negotiated settlement and accept less than they hoped takes a lot of work. That’s particularly the case when the conservative media constantly whips up the base regarding the alleged cowardice and lack of determination and principle on the part of the Republican leadership.

Passing Less Important Legislation Is No Easier

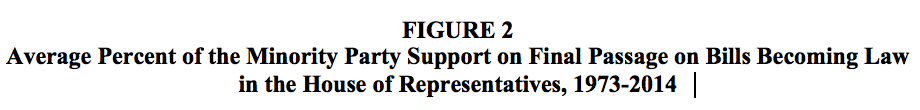

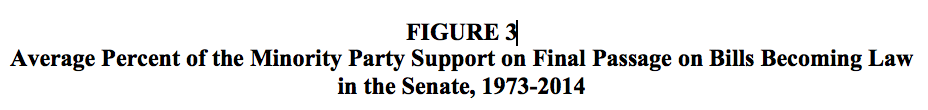

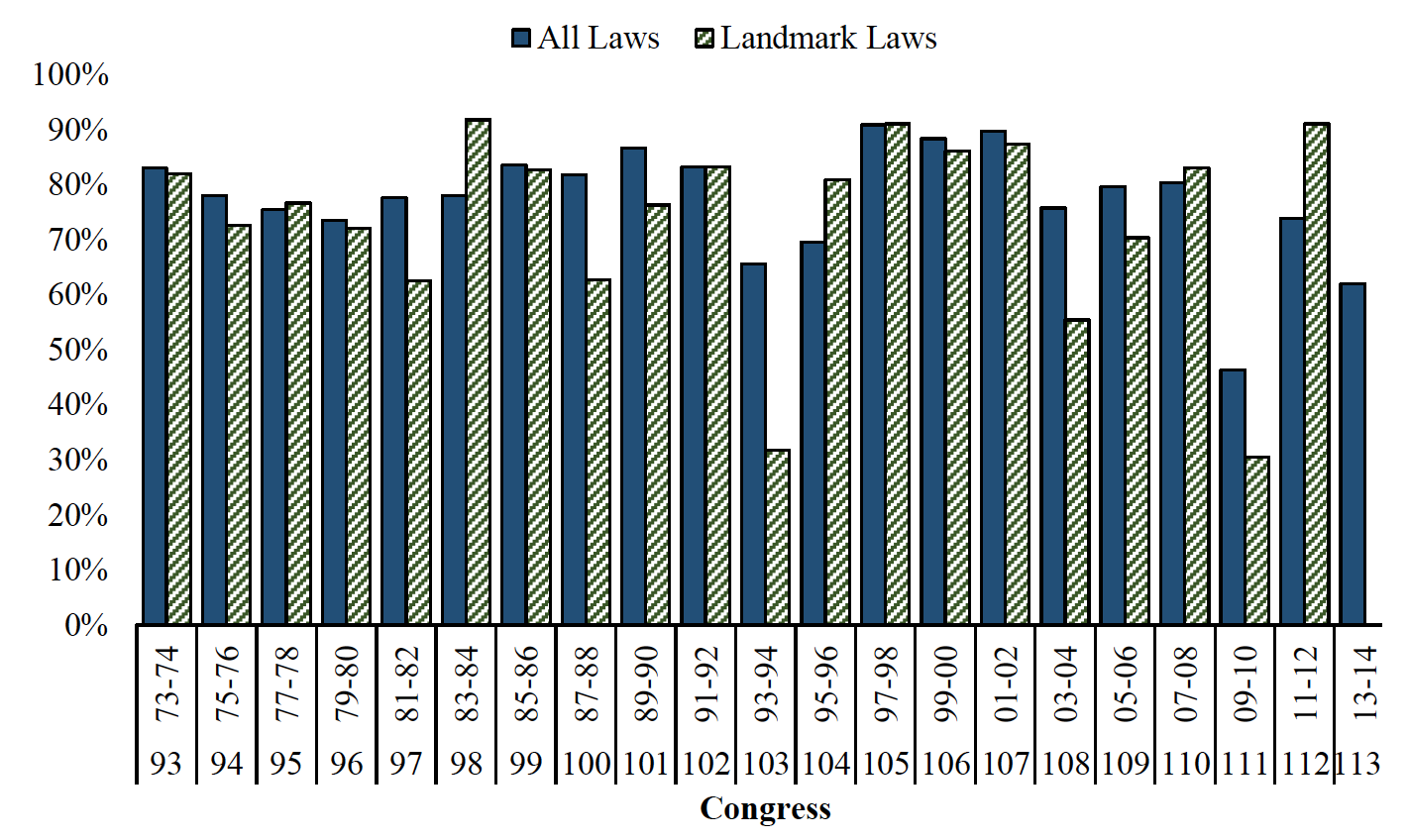

The task won’t get any easier for the Republican leadership once they leave their signature agenda items behind and turn to more prosaic legislative matters. Curry and Lee also examined two additional datasets: congressional votes on all enacted laws from 1973 to 2014, and congressional votes on landmark laws adopted between 1973 and 2012.

You can get the gist of Curry and Lee’s findings in six Figures. The first two require little explanation. (Votes on landmark legislation are unreported for the 113th Congress in all of these Figures because they are outside of the dataset produced by Yale’s David Mayhew, the source of the information marshaled by Curry and Lee on that matter).

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 1, p. 13.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 1, p. 13.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 2, p. 14.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 2, p. 14.

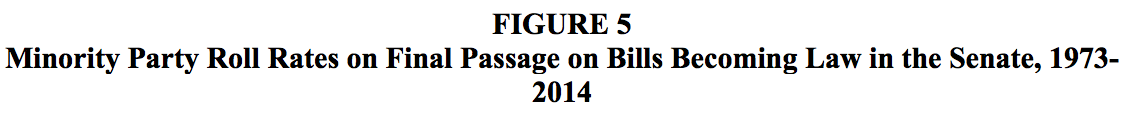

The next two Figures report on how frequently minority parties have been “rolled” by majority parties; that is, how often is a measure is passed despite a majority of that party voting in opposition?

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 3, p. 16.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 3, p. 16.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 4, p. 17.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 4, p. 17.

Even under unified government, the extent of bipartisan support for lawmaking remains roughly the same. Curry and Lee report that when it comes to enacting landmark legislation, roll rates are a bit higher under unified government. Even so, “the opposing party is rolled on less than half of landmark enactments in the Senate and on less than 60% of landmark enactments in the House.”

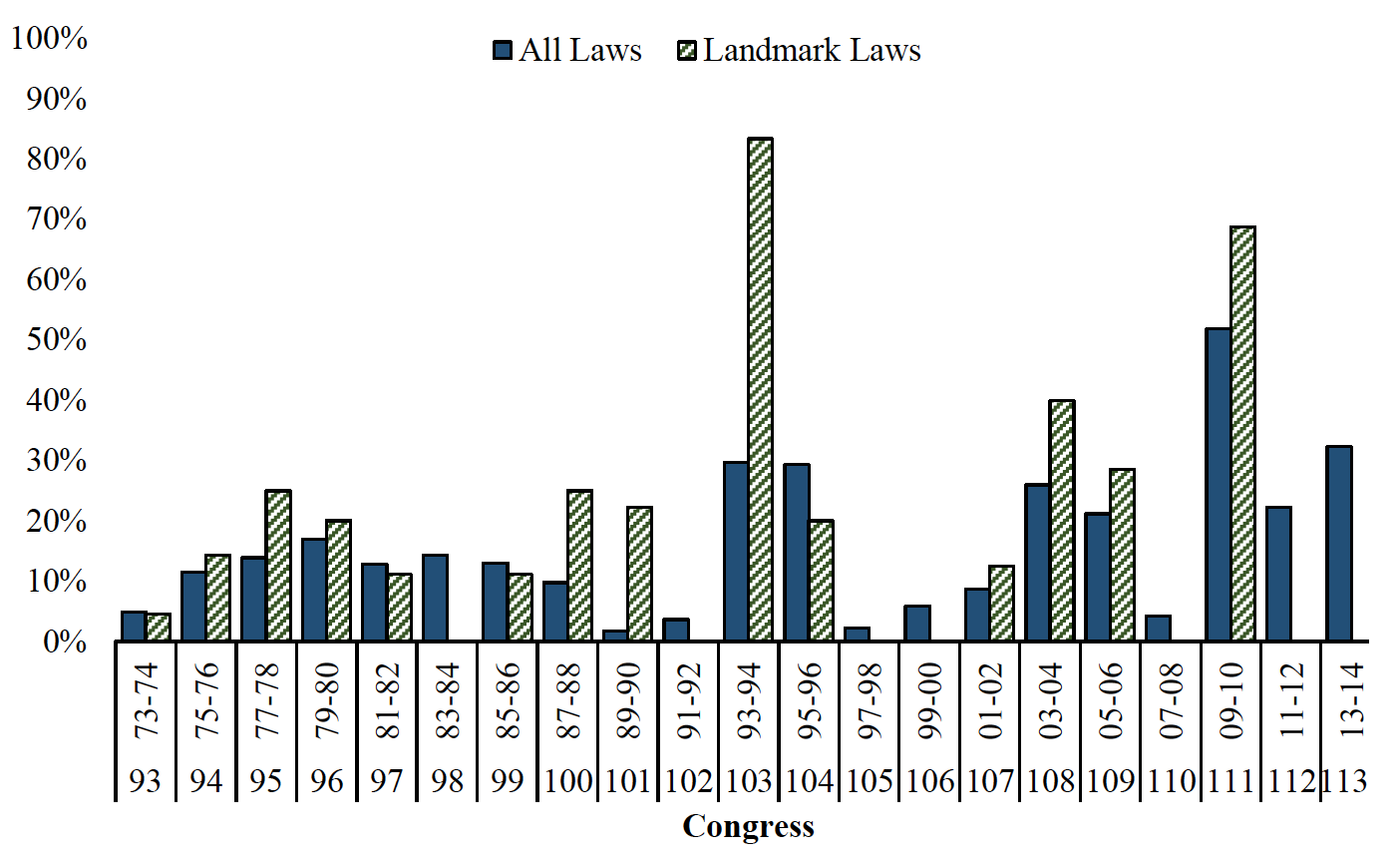

The final two Figures total the number of enactments where the majority party failed to muster a sufficient number of votes to pass the bill from among its own ranks alone. That is, how often did the majority party need minority party buy-in to pass legislation?

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 5, p. 20.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 5, p. 20.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 6, p. 21.

Source: James M. Curry and Frances E. Lee, “Non-Party Government: Bipartisan Lawmaking and Theories of Party Power in Congress,” Figure 6, p. 21.

These two Figures reveal that recent House majority parties have been no more self-sufficient in lawmaking than the House majority parties of the 1970s and 1980s. In the Senate—due to the filibuster—more minority votes are needed to pass bills, but no clear trend is evident in the time series. “Despite increased party strength in the House and Senate,” Curry and Lee conclude, “it appears [that] congressional majorities continue to need minority party votes to enact new laws just as often as in the 1970s and 1980s, if not more so.”

The big takeaway here is that America is not falling into a political state where congressional majorities are able to pound congressional minorities into jelly. After examining the data, Curry and Lee conclude:

Taken together, these six figures offer little evidence that congressional lawmaking has become more partisan. While the House majority party rolls the House minority party more frequently, when both chambers are taken into consideration it does not appear that contemporary congressional majorities are more frequently passing partisan laws. If anything, recent lawmaking may be more bipartisan[,] with Senate majority parties less frequently able to muster sufficient votes for enactment of legislation on their own.

The Partisan’s Case for Bipartisanship

The separation of powers, bicameralism, and electoral incentives all critically frustrate the ability of majority parties to enact their agendas. Divided government has been the rule, with different parties controlling Congress and the White House 69% of the time since 1954 and 79% of the time since 1980. Bicameralism frustrates majorities due to the greatly increased power of the minority party in the Senate, the longer terms and staggered election dates in the Senate (rendering them somewhat less responsive to public opinion than the House, especially following election waves), and the possibility of different parties holding different chambers at the same time. Most important, each congressional district (and for that matter, each state) is different, and members are frequently unwilling to defer to party leaders on policy questions at the cost of their own electoral security, even if doing so might have collective benefits for the party overall.

These obstacles to the unfettered exercise of majority party power cannot be remedied by “draining the swamp.” They are the consequence of constitutional design, not ill-intentioned political actors. Once in a blue moon, when the political stars align perfectly, the minority party can be rolled. But that’s a very low-probability event. Parties that bet on it are parties that usually have little to show for their efforts.

With both parties falling increasingly under the sway of their most zealous extremists, we run the risk of increasing dysfunction in the future. If unrealistic party agendas become the norm and compromise is equated with treason, Congress will grind to a halt. In that event, neither liberals nor conservatives will be happy—save for those perfectly content with the existing policy order.

Those pounding the table for major policy change will always be frustrated unless they can somehow convince the other party to go along with their agenda. And that requires compromise . . . sometimes, a lot of it. But rather than rail at the evil opposition in rage and fury, politicos would be well advised to find wisdom in the words of the Rolling Stones: “You can’t always get what you want. But if you try sometimes, you just might find, you get what you need.”

———————-

[1] Those ten successes include the Family & Medical Leave Act, the Motor Voter Law, and the omnibus crime bill passed by the Democrats in the 103rd Congress; Medicare Part D and the second round of the Bush tax cuts passed by the Republicans in the 108th Congress; the Class Action Fairness Act passed by the Republicans in the 109th Congress; the PAYGO rules passed by the Democrats in the 110th Congress; and the Affordable Care Act, Dodd-Frank, and SCHIP reauthorization passed by the Democrats in the 111th Congress.