California Congressman Ro Khanna has been turning heads recently thanks to his ambitious new proposal to double the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), the quasi-wage subsidy program that is often described as helping to “make work pay.” In a recent post, I argued that the proposal can be seen as a way of taking seriously the crisis of the “forgotten man” (and woman) — individuals who have been left behind by the decoupling of working class wages from broader economic growth.

In this post, I want to consider how a major expansion to the EITC would also help rectify a major practical deficiency with the current U.S. economic system — a deficiency which is already causing problems, and which will only worsen in an era of increased creative destruction.

I’m referring to the U.S.’s comparative lack of what economists call “active labor market policies” (ALMP). ALMPs are policies designed to reduce the inherent frictions of labor markets, and include things like worker retraining, job centers that facilitate efficient labor-market matching, and programs that provide laid-off workers with the basic tools they need to quickly bounce back.

A Trillion Dollar Gap in U.S. Labor Market Policy

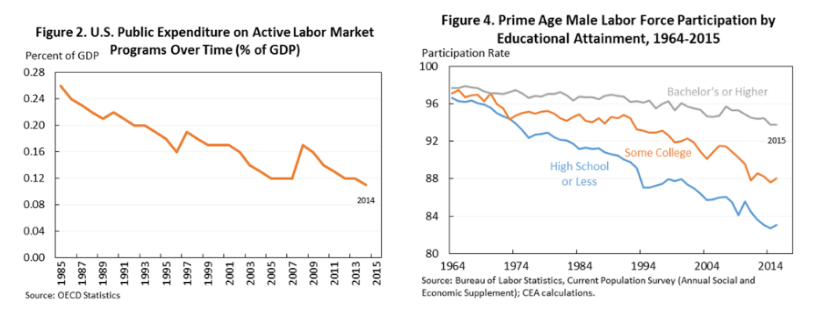

According to the OECD Employment Outlook 2016, the U.S. spends about 0.11% of GDP on programs that actively encourage labor force participation, the lowest of any OECD country besides Mexico and Chile. As the Council of Economic Advisors noted in a report last year, our low rate of ALMP spending is the result of a steady erosion that began in the 1980s — an erosion that doesn’t appear to have been a part of any deliberate policy choice, and which correlates well with secular declines in prime-age labor force participation.

For comparison, a country like Denmark has achieved what is perhaps the most dynamic labor market in the world by spending 1.91% of GDP on ALMPs. Anglo-American countries like Canada and Australia expend at least twice what the U.S. does, while Germany, which instituted a highly successful wage subsidy program in the early 2000s, expends about 0.66% of GDP on ALMPs.

The details of Khanna’s plan are still being formulated, but early versions put the cost at roughly $110 billion per year, which translates to increasing America’s expenditure on ALMPs by 0.61% of GDP, to a total of 0.72%. That would push the U.S. a bit above the OECD average of 0.55% of GDP. While no small amount of money, pushing the U.S. a bit above the international average is not exactly radical, especially for a country which prides itself on its economic dynamism.

Why Wage Subsidies?

The effectiveness of different ALMPs varies widely, with wage subsidies being among the more consistently successful strategies for lubricating labor markets. In contrast, while worker retraining and job-search programs can also work well, they suffer from inconsistent implementation due to problems with public administration, including the inherent knowledge problem that comes from trying to divine what displaced workers ought to be retrained for.

A much larger EITC, particularly for childless adults, would decentralize the job search prerogative to workers and firms. In the jargon of economics, the credit acts to increase search intensity. Workers become coaxed by the carrot of a steep on-ramp to decent take-home pay, while employers increase search efforts because they get to capture a small fraction of the EITC for themselves. This drives firms and workers to aggressively seek each other out.

In general equilibrium, labor markets end up being both tighter and more fluid, since employees have more confidence that they’ll be rapidly re-hired if they quit. That also means job-matching improves, and labor is allocated in a more productive way. The theory also shows that unemployment will decrease even as participation increases, with previously discouraged workers (i.e. workers with “low search intensity”) re-entering the labor force. Indeed, wage subsidies are one of the few policies where politicians can truthfully brag about job creation — they actually increase the total stock of jobs for a given population, rather than merely reallocate labor between sectors.

An Economy Needs Shock Absorbers

In the long shadow of the Great Recession, job creation is perhaps one of the most important facets of Khanna’s plan. The slowness of our recovery is a function of labor market hysteresis, the phenomena whereby the initial hit to participation and employment caused by the recession persists, since the skills of long-term unemployed degrade over time, and others simply lose interest in ever working again. Indeed, the growing number of prime-age workers who have dropped out of the economy is among the top issues being discussed by policy makers today. A major expansion to the EITC, particularly to childless adults, would provide a meaningful incentive to discouraged workers to start looking for a job again.

The U.S. has skirted by without much by way of active labor market policies, in part due to its large size. A small economy like Denmark cannot sit on its laurels, since having 55% of GDP go to exports means the composition of Danish jobs is at the mercy of ever-changing global markets. And yet, as the economics profession is learning, the U.S. is not immune to trade shocks, either.

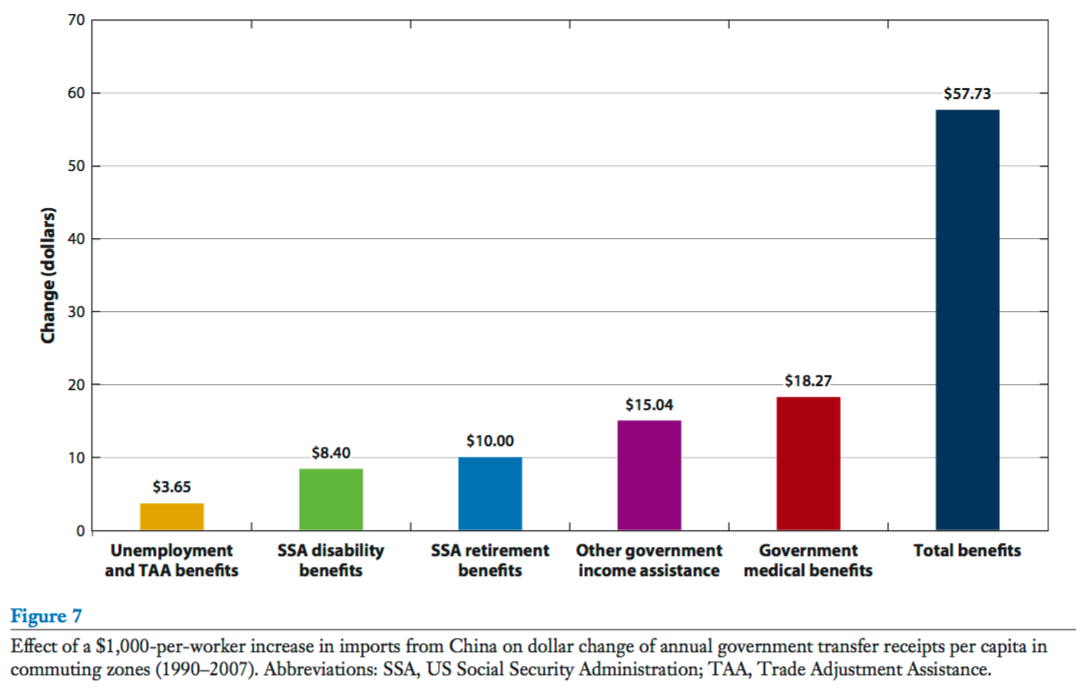

As David Autor and co-authors showed in a widely cited paper, establishing normal trading relations with China caused a one-time shock to U.S. labor markets in the 2000s that displaced over a million workers and significantly depressed wages in affected regions. The simplistic model from neoclassical economics suggested these workers would be quickly absorbed into other jobs, and not suffer any persistent harm. But that was not the case. Indeed, the impact has been quite persistent, and in some measure appears to have been the catalyst for the rise of anti-trade populism.

The core failing of the classic model is the assumption of frictionless labor markets. Add in significant labor market frictions and suddenly persistent, concentrated harms from trade liberalization become not just possible, but probable. And, as Autor et al. have argued, in many ways the existing U.S. tax and transfer system made things worse, as some of those who became detached from the labor market sought refuge by retiring early or joining disability roles. The negligible uptake of Trade Adjustment Assistance (our paltry and unpopular program for dealing with trade shocks) was a stark confirmation of the existing system’s inadequacy.

“The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade,” Autor et al., 2016

In contrast, a more generous EITC would have put a floor beneath earnings, encouraged re-hiring, and made programs like disability look less attractive. Put differently, by smoothing out labor market frictions, a doubling of the EITC would have made labor markets behave more as they should within a neoclassical model, protecting popular confidence in future trade liberalizations.

Implementation Matters

The big caveat is that the EITC comes as a lump-sum tax refund, and thus doesn’t differentiate between someone who works a few hours at a high wage, and someone who works many hours at a low wage, and yet earn the same amount. Thus making the EITC into a true wage subsidy, along the line as has been proposed by Oren Cass, is an important next step for improving the EITC’s effectiveness as a market lubricant. The improvements it would bring to fraud detection alone make it an important prerequisite to Khanna’s plan, since doubling the credit amount without administrative reforms will simply exacerbate the current problems with the lump sum mechanism.

But this is getting too deep into the weeds for one post. In a future post, I will chart out precisely how I think Khanna’s plan can be better formulated for maximum effectiveness, and also show how a more much generous EITC will help prepare us for the uncertain future of work.