What drives opposition to immigration? This is a profoundly important question. Liberalizing the movement of people over borders would produce enormous gains in human well-being. According to the economist Michael Clemens:

The gains from eliminating migration barriers dwarf—by an order of a magnitude or two—the gains from eliminating other types of barriers. For the elimination of trade policy barriers and capital flow barriers, the estimated gains amount to less than a few percent of world GDP. For labor mobility barriers, the estimated gains are often in the range of 50–150 percent of world GDP.

“When it comes to policies that restrict emigration,” Clemens writes, “there appear to be trillion-dollar bills on the sidewalk.” It’s important to note that most of the benefit from the liberalization of travel and work would redound to the relatively poor. Clemens is offering a quantification of the poverty and suffering we could have relieved, but haven’t.

Of course, entirely eliminating barriers to labor mobility isn’t in the cards. The gains from reducing barriers to migration mainly flow from people leaving jurisdictions in which the productivity of their labor is low, and resettling in jurisdictions in which it is high. But the world’s highest-productivity labor markets are located in liberal democracies with large welfare states. Questions about equitable distribution and national identity loom large in these polities, and high barriers to immigration are constantly re-affirmed by their democratic bodies. On a continuum running from completely open to completely closed borders, the most immigrant-friendly countries in the world are just a few steps away from “completely closed.” It may be the case that the political dynamics of the liberal-democratic institutions that sustain high-productivity labor markets—the existence of which drive Clemens’ jaw-dropping estimate—make it unlikely that more than a tiny fraction of outsiders will ever be granted access to those markets.

Indeed, it can be a heavy lift keeping barriers to migration from hardening further. Donald Trump swept into the White House promising to ban Muslim immigration and to build a literal wall along our border with Mexico. If we misdiagnose why these were attractive promises to Republican voters, we have little hope of collecting even a dollar of Clemens’ trillions. So it’s important to get it right.

That’s why the recent essay here by Jeffrey Friedman, the Director of Niskanen’s Institute for the Study of Politics, is important. Friedman’s purpose in this characteristically lucid and penetrating essay is to divine the roots of Donald Trump’s electoral support. In particular, he argues, drawing on the scholarship on attitudes toward immigrants, that “the xenophobia theory”—the idea that antipathy toward outsiders was critical to Trump’s electoral success—is false.

This is an intriguing, counterintuitive claim. Trump is the most overtly xenophobic and ethnocentric major-party presidential nominee in living memory. His transparent hostility to Mexican immigrants and Muslim refugees set him apart from the crowded field in the Republican primaries, which he won decisively. And it would seem that Trump could not have claimed victory over Clinton in an extremely tight election had his blatant bigotry turned off Republicans who had opposed him in the primaries. But it clearly didn’t bother them enough to cross party lines or stay home on Election Day.

Friedman agrees that Trump’s success was due in large measure to his oppositional stance on immigration. But he argues that xenophobia doesn’t drive opposition to immigration, nationalism does. And that’s why he concludes that the xenophobia theory of Trump’s success is false.

I’m not convinced. Now, I’m personally not that interested in why Trump won. (I think if we could go back to November 2016 and give the wheel nine more spins, it would stop on “Clinton” six or seven times.) But I’m keenly interested in why some Americans so hotly oppose immigration. I want to know exactly what’s keeping us from picking up trillion dollar bills. In any case, if Friedman is mistaken about the sentiments that drive opposition to immigration, then he’s probably mistaken about the sentiments that drove support for Trump.

Friedman contrasts “xenophobia” and “nationalism,” but I’d like to reframe what I take him to be saying in in terms that make the contrast more immediately intuitive. (To many of us, xenophobia and nationalism go hand in hand.) Friedman suggests, quite correctly, that in-group favoritism (“nationalism”) need not imply hostility to out-groups (“xenophobia”). He goes on to argue that opposition to immigration is driven mainly by in-group favoritism; out-group hostility is less important, if it’s important at all. I think opposition to immigration is driven by both, and at least as much by out-group antipathy as by in-group favoritism. The evidence Friedman adduces to minimize the importance of out-group antipathy does not seem to me to actually support his claim.

Politics Is Groupish

The upshot of several decades of research on political behavior is that voters know next to nothing about politics and policy, aren’t very ideological, and tend to vote in groups defined by personal and social identities—race, religion, class, etc. We don’t identify as Democrats rather than Republicans, or vice versa, because that particular party is the best match for our well-worked-out policy preferences. (We don’t know enough about policy to have clear and independent preferences.) Rather, we identify as Democrats or as Republicans because people like us identify as Democrats or Republicans. Once we’ve assumed a partisan identity, usually on the basis of a more fundamental social identity (e.g., union member, African American, evangelical Christian, etc.), we mostly just go along with whatever our party happens to be currently saying—if (and this is a much bigger “if” than news-junkie wonk types tend to imagine) we happen to be sufficiently clued in to what our party is saying.

As Princeton’s Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels of Vanderbilt emphasize in Democracy for Realists, this “group theory of democracy” implies that civics-class ideas about “the will of the people” are wrong-headed. “Public opinion” isn’t out there waiting to be channeled into policy by the democratic process. On the contrary, insofar as typical voters have opinions on policy at all, those opinions come to them through partisan affiliation, and their partisan affiliations come to them through group identity. As Niskanen’s own Steven Teles has argued (with David Dagan) in Prison Break: Why Conservatives Turned against Mass Incarceration, the group theory of democracy means that the policy positions of voters—and even politicians—can be quite malleable in response to new signals from respected group leaders.

The public’s radical political ignorance and utter lack of ideological coherence suggest that many people will have “non-attitudes” on many issues. When we’re prompted to offer an opinion about obscure-to-us subjects, we’re inclined to assemble one on the spot from hazily recalled snatches of news segments and Facebook posts. If prompted later, we may assemble a totally different answer. Clearly, that doesn’t amount to an actual change in opinion. That’s just typical, low-info, low-ideology confabulation. That’s just humans. Once you really grasp that “public opinion” is, by and large, an artifact of partisan identification, media coverage, and people wanting to not look dumb, you can never look at an opinion survey the same way again. Public ignorance and ideological innocence is the political science red pill.

Following this line of research, Friedman raises the possibility of whimsical improvisation around non-attitudes to sow doubt about whether “‘an exclusionary notion of American identity’ had a significant grip on Trump supporters, and that such restrictive views had played ‘a major role in the Trump campaign.’”

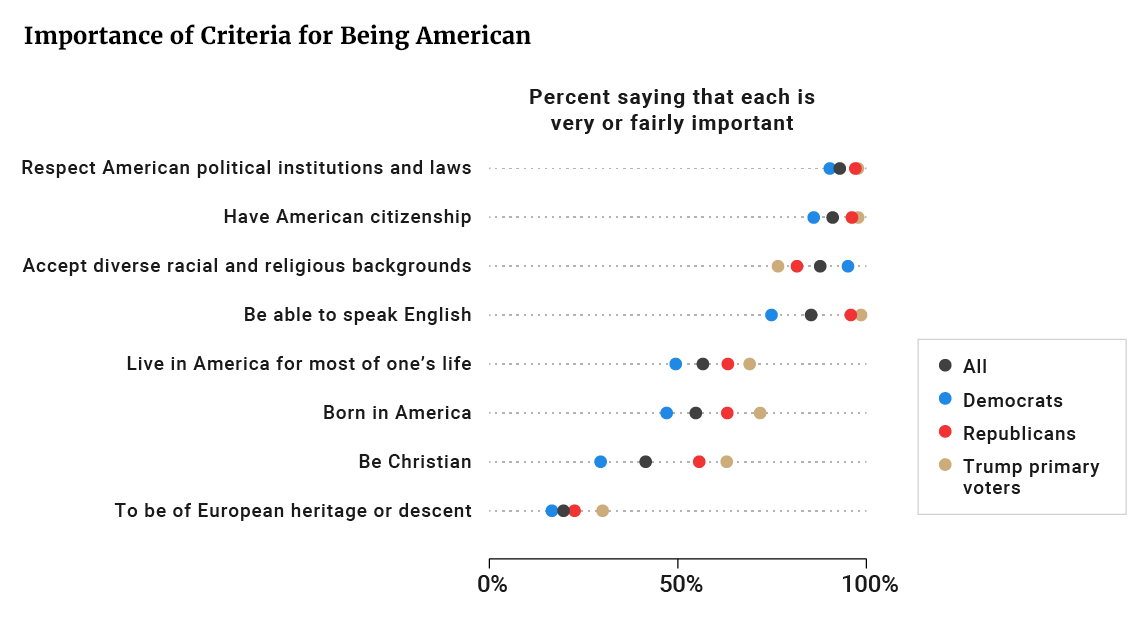

Here’s an illustrative graph, from George Washington University political scientist John Sides’s study for the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group:

Source: Democracy Fund Voter Study Group

This is pretty telling to me. Most Republicans seem to think you need to be a Christian non-immigrant to count as a full-fledged member of the national in-group, and these views were especially prevalent among Trump primary supporters.

But maybe, Friedman suggests, respondents hadn’t previously thought much about the importance of European heritage. He argues that based on what we know about the shallowness of survey responses, people confronted with this unfamiliar answer on the survey may have winged it. Maybe. But I think it’s much too quick, and more than a little unfair, to dismiss this finding on the basis of such general concerns about non-attitudes.

According to the group theory of democracy—the best empirical account of political behavior going—we’re least likely to have volatile non-attitudes on subjects that bear on group identity. The lines that divide “us” and “them” are exactly what people do have clear, strong, consistent ideas about, even if the way this cashes out in specific policy terms is quite flexible (e.g., should we build the wall or pursue internal enforcement?). If group membership grounds and structures our other political attitudes, then the questions we’re going to be clearest about about are questions about who does and does not count as a member of our group.

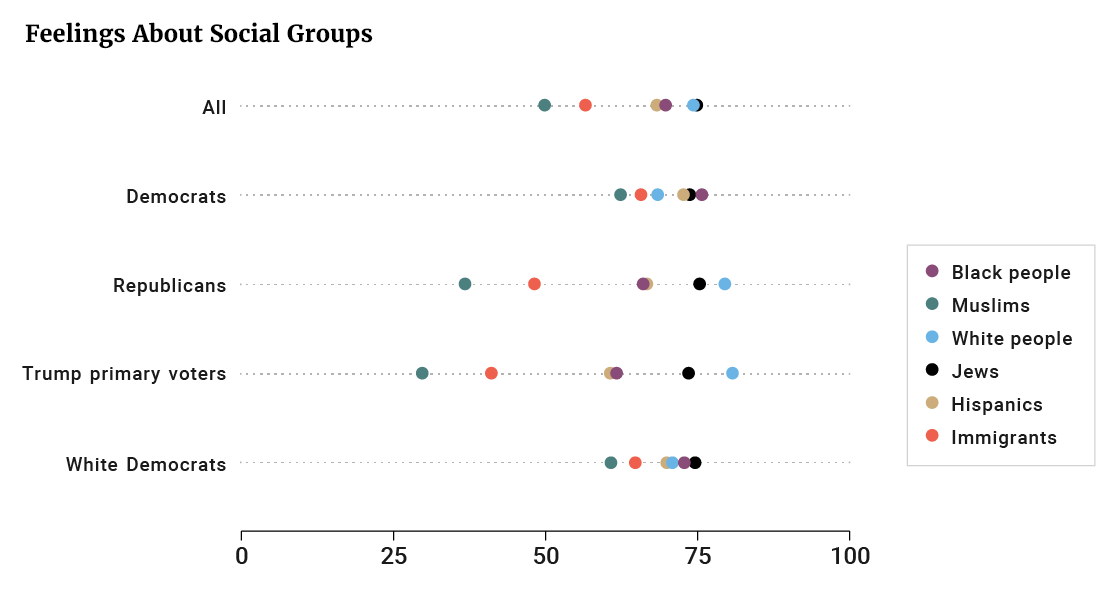

Here’s another chart from the same study, illustrating patterns in feelings about various groups measured on a 0-to-100, cool-to-warm “feeling thermometer” scale:

Source: Democracy Fund Voter Study Group

Are there Americans who have never had a positive or negative feeling about immigrants or white people? Seems doubtful. And here we see that Trump primary voters (followed by Republicans generally) are warmest about white people and coolest about immigrants. The fact that the pattern of feeling-thermometer responses comports so well with our expectations and the pattern of responses to the survey questions about what is and isn’t important to being American should reinforce the sense that those responses are picking up on real, stable attitudes.

Ethnocentrism Drives Opposition to Immigration

A feeling of special warmth toward one’s own in-group is evidence of in-group favoritism. As Michigan’s Donald Kinder and Cindy Kam of Vanderbilt show in Us Against Them: Ethnocentric Foundations of American Opinion, thinking and feeling especially highly of one’s in-group (what they call “ethnocentrism”) does not correlate generally with hostility to out-groups. But very cool feelings (along with negative stereotypical beliefs) about specific outgroups is clear evidence of out-group hostility. A group of highly self-favoring people with extremely negative views specifically about Muslims and immigrants, as an undifferentiated category, is very reasonably labeled “xenophobic.”

Individuals vary in their degree of ethnocentrism, as Kinder and Kam define it. They construct their measure of ethnocentrism from a battery of questions in the General Social Survey and the National Election Study which ask respondents about their beliefs and sentiments about various ethnic groups. Some individuals answer these questions in ways that exhibit no in-group favoritism while others exhibit intense in-group favoritism. Kinder and Kam maintain that an individual’s level of ethnocentrism is a fairly stable personality trait. On average, Americans are mildly ethnocentric, displaying just a bit of bias toward their in-groups. But, again, people who are more positive about their in-group are not generally likely to be especially negative about other groups.

Kinder and Kam’s simple measure of ethnocentrism has surprising independent explanatory power in predicting individual positions on many policy issues. Crucially, it is not a redundant variable. It is not generally correlated with partisan affiliation. (If this is surprising, consider that black, Asian, and Latinx Americans are just as likely to exhibit in-group favoritism as are white Americans.) Ethnocentrism is only very weakly positively correlated with ideological “conservatism” and only very weakly negatively correlated with “egalitarianism.” And it is especially predictive of views on immigration.

Kinder and Kam find that, among whites and blacks, a high level of ethnocentrism strongly predicts support for reducing the rate of immigration, and it does so more strongly than other variables, such as a high level of “moral traditionalism” or a low level of “egalitarianism.” The interesting wrinkle here is that, for Hispanics and Asians—groups that identify as or with immigrants—ethnocentric in-group bias predicts support for immigration. Overall, however, ethnocentrism is one of the main factors driving opposition to immigration. “Indeed,” Kinder and Kam write, “… ethnocentrism emerges as the single most important determinant of American opposition to immigration—across time and setting and for various aspects of immigration policy” [emphasis added].

Logically, ethnocentrism-driven opposition to immigration could occur without hostility to out-groups. As a matter of fact, out-group scorn is a big part of it. Kinder and Kam write:

both in-group loyalty and out-group hostility make significant contributions to opinion, and on each and every aspect of immigration policy. Between the two, denigration of out-groups is consistently more important. But the main story is that both attachment to in-groups and disdain for out-groups figure importantly in opinion on immigration [emphasis added].

Are Immigration Worries Mainly Just Concerns about In-Group Well-Being?

Friedman cites several studies that he thinks suggest that opposition to immigration is driven by “the perceived effects of immigration on the economic or other interests of current American citizens.” Friedman speculates that “rather than opposing immigration because of a dislike of immigrants in general, or a dislike of immigrants from a particular country, Americans may oppose immigration out of a desire to serve or defend the interests of their fellow Americans (defined not as those of European descent, but those who qualify as American citizens already).”

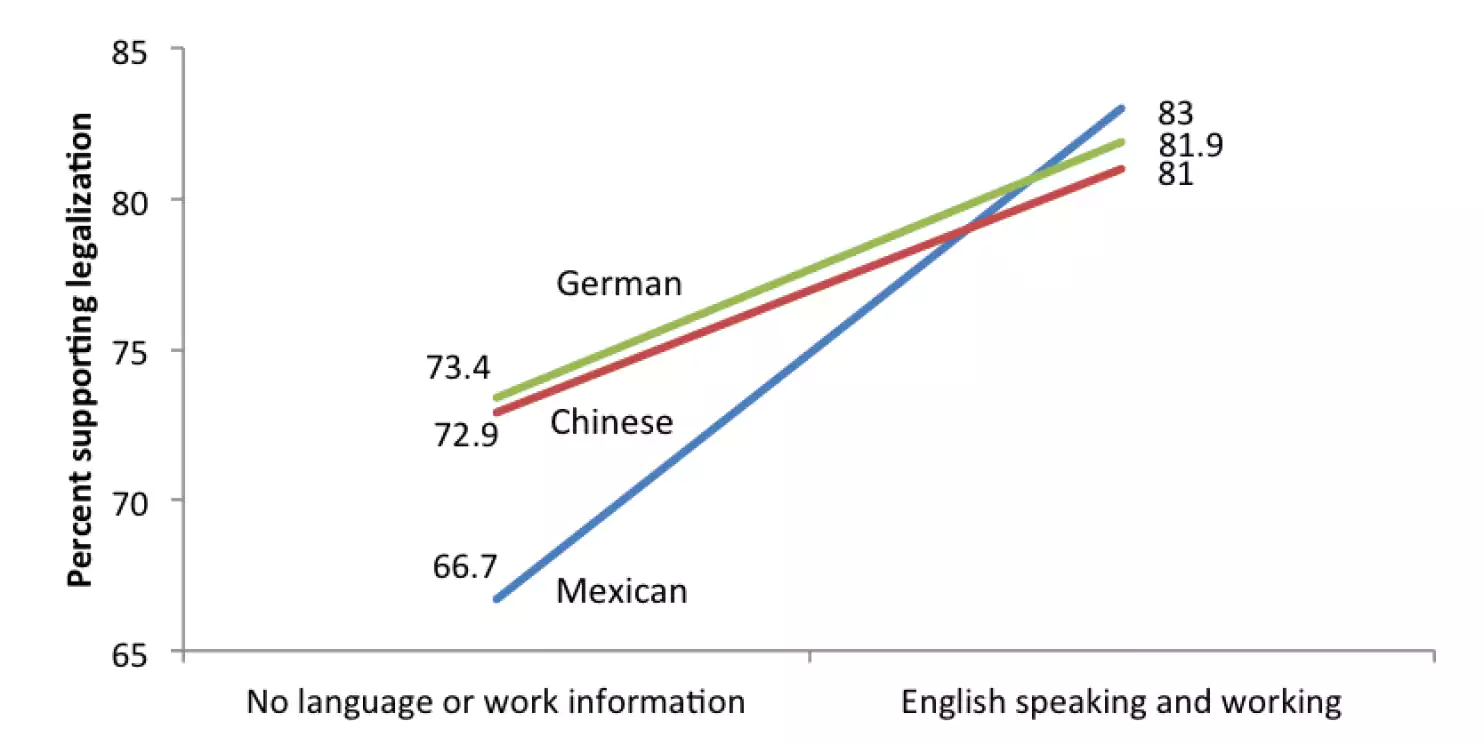

For example, USC’s Morris Levy and Matthew Wright of American University find that bias against offering legal status to an undocumented Mexican immigrant, relative to an undocumented German or Chinese immigrant, disappears entirely when the Mexican immigrant is characterized as an English speaker with a job. But Levy and Wright are wrong to suggest that this is not evidence of a lack of “anti-Latino bias.” They write:

Discrimination against Latinos may grow not from hostility against an ethnic “outgroup,” but rather stereotypes about whether they will contribute to the United States or become a burden. In the absence of other information, whites in our sample rely on ethnic cues to “fill in the blanks” — assuming undocumented Latinos are uneducated, unassimilated and potential financial problems for U.S. society.

Here’s a visual summary of Levy and Wright’s findings:

Source: The Monkey Cage, Washington Post

As a matter of empirical fact, poor English skills and the lack of a steady formal-sector job don’t make undocumented immigrants unlikely to contribute positively to the economy or to add more than they subtract to public treasuries. Now, we can’t reasonably expect ordinary Americans to know this. But the assumption that it’s true, and that it’s especially likely to be true for Mexicans, betrays a less than flattering, if not outright hostile, picture of Mexicans. If hostility to ethnic out-groups is a live possibility, and you wanted to go out looking for it, what you’d be looking for is a pattern of reliance on “ethnic cues” to “fill in the blanks” with “stereotypes” that imply social uselessness or parasitism or threat.

Consider an analogy. Suppose a white mother, Laura, actively avoids sending her child to a nearby elementary school with a high concentration of black children due to deeply held negative racial stereotypes about black people. She thinks that, other things equal, blacks are less intelligent, less hard-working, and more unruly and violent than whites. It would be fair to say that Laura’s schooling choice is being driven by racism, a form of out-group hostility (which need not generally entail any manifestation or awareness of explicitly hostile feelings). Now suppose we ask Laura if she would be willing to send her young daughter to a school with a high concentration of the children of very wealthy, highly educated, high-achieving black doctors, lawyers, and executives. If Laura were to say, sensibly enough, that this must be an outstanding school, and that she would be willing to send her child there, this would not count as evidence of a lack of racist attitudes on Laura’s part. This response would be perfectly consistent with the racist attitudes she’s currently acting out in her decisions about where to send her daughter to school.

Stanford’s Jens Hainmueller and Georgetown’s Daniel Hopkins show that when presented pairwise choices about which of two prospective immigrants they’d rather admit to the country, the admission choices of Americans are very sensitive to potential immigrants’ education, economic prospects, and fluency in English, but aren’t very sensitive to their country of origin. Overall, there’s a surprising level of agreement across partisan lines about which immigrants are considered most desirable, if we’re going to have immigrants. However, Hainmueller and Hopkins also show, following Kinder and Kam, that country of origin does matter for those high in ethnocentrism. They write:

More ethnocentric respondents impose somewhat more of a penalty for immigrants from non-European countries.This negativity is pronounced for immigrants from countries with significant Muslim populations, but it extends to Mexico, China, and the Philippines as well. More ethnocentric respondents also place less emphasis on the immigrant’s occupation.

You’ll recall that Kinder and Kam find that ethnocentrism is the single variable most strongly correlated with opposition to immigration. So Hainmueller and Hopkins effectively show that those most likely to oppose immigration are also least impressed by occupation and most biased against non-Europeans, Muslims, and Mexicans. This doesn’t strike me as evidence that opposition to immigration is driven by in-group favoritism rather than out-group hostility. To the contrary, this is exactly what we would expect to see if Kinder and Kam are correct that out-group antipathy has a larger effect on opposition to immigration than in-group bias.

Of course, a study about which immigrants Americans want to let in if we’re going to let in immigrants does not tell us why Americans who don’t want to let in immigrants don’t want to let in immigrants. In their outstanding review of the literature specifically on the question of what drives opposition to immigration, Hainmueller and Hopkins note that it’s very tricky disentangling “sociotropic” concerns about the broad effects of immigrants on the economy and the material interests of citizens from cultural concerns driven by distaste for out-groups. “If immigrants who speak the native language are preferred for admission, is that because of their perceived economic contribution or the reduction in the cultural threat they pose?” Hainmueller and Hopkins wonder. “Conversely, are immigrants with low occupational status a concern because of their possible need for public support or because of cultural conceptions about the centrality of work to American identity?”

They don’t know, and they don’t see their findings on which immigrants are most preferred as evidence against the idea that opposition to immigration is largely driven by worries about “cultural threat” or “American identity.” They think it’s perfectly consistent with a large body of research in which, “Very consistently, prejudice and ethnocentrism have been connected with increased support for restrictive immigration attitudes” [emphasis added.]

To cite just one more example of that literature, the economists David Card, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston find that, in Europe, most of the difference on the question of whether immigration should be increased or decreased can be explained by differences in “the value that people place on having neighbors and co-workers who share their language, ethnicity, culture, and religion,” and that relatively little of the difference in support for immigration can be explained by economic concerns.

There certainly is evidence that “Americans . . . oppose immigration out of a desire to serve or defend the interests of their fellow Americans,” as Friedman suggests. But this generally doesn’t count as evidence that it’s not driven by xenophobic distaste for foreign others. Many Americans who oppose immigration seem to be serving and defending the interests of their fellow Americans to not live in a country with people who don’t look, speak, or worship like them. What does it say about your attitude toward Muslims if you think keeping them out of the country protects your fellow Americans from terrorism? What does it say about your view of Mexicans if you think keeping them out of the country protects your fellow Americans from crime or from paying more in taxes to finance the dole? Nothing good. You certainly wouldn’t say that somebody who doesn’t want his kids to hang around Jewish people because he think Jews kidnap and murder Christian children is just looking after his kids.

Why Xenophobia Is Worse than Nationalism

I don’t think it’s the case, as Friedman contends, that in-group favoritism, construed as “nationalism,” ought to worry us just as much as out-group hostility, or xenophobia.

Xenophobia, which is most commonly understood as an aversion to foreignness and those who seem strangely other, is an element of nationalism, in the sense of “nationalism” currently under public discussion. Trump’s promise to “Make America Great Again” is a classic piece of populist nationalism. As the Princeton political theorist Jan-Werner Müller explains, populism works by rigging a conception of “the people” or “the nation” through an exclusive, anti-pluralistic conception of national identity. “The only important thing,” Trump declared at a rally in May of last year, “is the unification of the people, because the other people don’t mean anything.”

Xenophobic sentiment and a drive to exclude non-white, non-Christian, non-English-speaking Americans from full and equal membership in the political community seem obviously related.

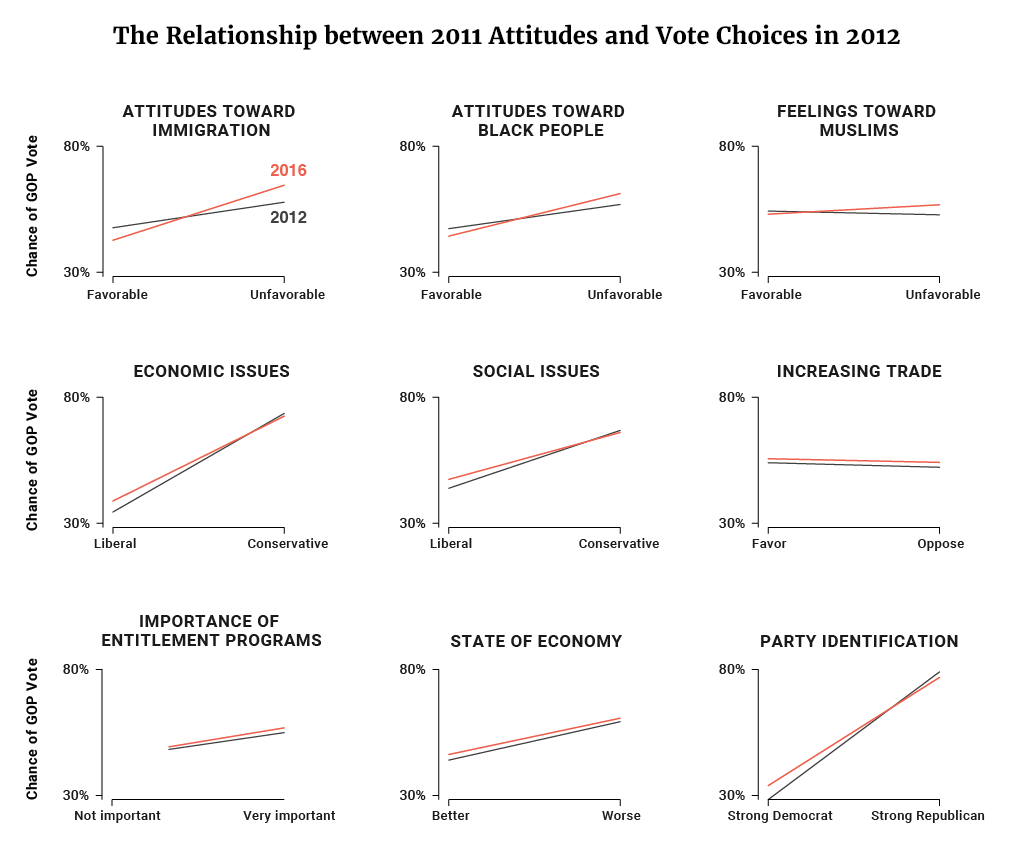

As we’ve seen, out-group hostility drives opposition to immigration. And, as Sides shows, it drove Democrats who had voted for Obama to support Trump. Comparing the determinants of the 2012 and 2016 presidential vote share, Sides writes: “What stands out most . . . is the attitudes that became more strongly related to the vote in 2016: attitudes about immigration, feelings toward black people, and feelings toward Muslims.”

You can see the relationships here:

Source: Democracy Fund Voter Study Group

Kinder and Kam have noted that the political effects of ethnocentrism are not constant. Ethnocentrism waxes when it is “activated” by party elites and the media, and wanes when other considerations dominate voters’ limited attention. Sides offers pretty persuasive evidence that Trump successfully activated the most powerful determinant of opposition to immigration, and that this was critical to his electoral success.

I think this suggests that if we’re going to have any hope of picking up any of Clemens’ trillions through reduced barriers to immigration, our first priority ought to be understanding and learning to better defend the cultural and political norms that suppress the activation of ethnocentric political motives. Focusing on in-group favoritism, construed in terms of partiality toward fellow citizens, may be worthwhile once we’ve got a grip on how to dampen the activation of out-group hostilities that harm citizens and foreigners alike. But as long as we’re subject to demagogues who can win elections by whipping ethnocentric voters into a xenophobic froth, we’re unlikely to get very far in the urgent task of beating back barriers to mobility. Pointing out that legal nationality is arbitrary from the empyrean perspective of morality will only take us so far.

Few of our group identities are underwritten by nature or abstract normative principles, and legal nationality is no exception. But nationality does not therefore lack “normative significance,” as Friedman argues. Our group affinities supply us with many of the norms we build our lives around. The difficulty, it seems to me, is that nationality, like other contingent historical identities, is too normatively significant.

Of course, what we’re motivated to do and what we ought to do are different matters. But obligation and motivation are intricately related, and especially in politics, which chugs along on the volatile fuel of normatively dubious group identity. If politics is inevitable, necessary, and essentially groupish, a descriptively adequate and normatively useful theory of politics won’t be too squeamish about accommodating groupishness. That’s why I don’t think that “whether one should identify oneself with people in the past who happened to live in the same geographical area in which one now lives” is the question, as Friedman maintains. Defining ourselves in terms of these sorts of collective identities is just something people do, for better or worse. To my mind, the question is what we can do to make this fact about humans and human political life work for the better rather than the worse. How can we keep existing tribal rivalries from flaring up? How can we promote a more inclusive sense of the psychologically salient in-group? From this perspective, a form of nationalism that puts Chinese-Americans in Seattle inside the same circle as Cuban-Americans over 3000 miles away in Miami looks a lot like progress. But this nationalism is a far cry from Trump’s nationalism.

Trump’s nationalism is a form of in-group partiality, for sure. But the relevant in-group is, as Müller suggests, a subset of American citizens who approximate an exclusive populist conception of American national identity. The relevant out-group, then, includes other American citizens, as well as foreigners. The form of nationalism Friedman examines in his piece is more legalistic and less cultural, drawing the in-group/out-group distinction in terms of shared citizenship. I agree that opposition to immigration is driven in part by the widespread sense that we have special obligations to co-nationals that we do not have to foreigners, and that this leads many of us to be overly concerned about the effects of immigration on the welfare of our fellow citizens, and insufficiently concerned about its effects on the welfare of prospective migrants. And it is true, as Friedman says, that most liberals agree with conservatives in granting relatively more weight to the welfare of compatriots and less to the welfare of those who might become our compatriots, were we to let them.

But the standard form of liberal civic nationalism is egalitarian within the in-group of shared citizenship. Citizens get equal weight, period. Nativity, race, religion, languages spoken, etc. simply don’t matter. The legal status of citizenship locks in a moral and political status equal to other citizens. In our current political context, that seems like a dream. Populist nationalism, in contrast, is inegalitarian within the in-group of shared citizenship. Indeed, for populist nationalists, the set of American citizens is not the focal in-group, except in times of war. The rest of the time, the focal in-group is the group that more or less conforms to the ideal of American identity. Many fellow citizens—elites, globalists, members of the mainstream media, despised minorities, immigrants, Muslims, city people, pointy-headed liberal intellectuals, etc.—are therefore consigned to the liminal out-group of less-than-fully-American Americans. Nationalists of this stripe are notably given to xenophobic aversions, as well as to enthusiastic in-group solidarity. And this means that they tend to doubly discount the welfare of foreigners relative to members of their focal in-group: first for falling outside the bounds of their exclusive culturally coded conception of American identity, and then for not being even technically American.

A strong sense of out-group hostility tends to entail a strong sense of in-group favoritism, but the reverse isn’t true. People who really dislike people in other groups almost always think especially highly of members of their own group. But people who think especially highly of members of their own group are all over the map about people in other groups. That’s why out-group hostility (or xenophobia) is worse than in-group favoritism, both in general and when the scope is specified as the set of citizens. When you’ve got xenophobia, nationalism comes along as part of the bargain.

—

Will Wilkinson is Vice President for Policy at the Niskanen Center