Former-Texas governor and rumored presidential aspirant Rick Perry told the Iowa Ag Summit this week that America needs to spend more on tracking foreign workers. While the governor is certainly right that the government could improve its records on the number of people who overstay their visas generally, there is little evidence that he should worry about guest workers, a class of foreign visitors who rarely overstay.

Gov. Perry’s point is well-intentioned. He wants to focus immigration reform efforts on “bringing people into this country that we need, whether it’s high-tech workers, or people in agriculture, hospitality or construction.” But he’s concerned that without a new program to track when (and if) workers leave, temporary worker programs will result in more illegal immigration rather than less. “If UPS can track a box all around the world,” he said, “we can give people a card and allow them in here and say that when you hit your visa limit … we’re going to know where you are.”

Concern about visa overstays is not misplaced. The Pew Research Center has found that about 44 percent of the illegal population entered lawfully and overstayed. But the available evidence indicates that the vast majority of these overstays were from people who entered as tourists or temporary business travelers, not as guest workers.

Although Department of Homeland Security (DHS) does not have a biometric exit system, it does track foreigners’ departures through airline flight manifests. By comparing entries of foreign visitors who arrive at airports with records of departures through the air, DHS can estimate the number of people who have remained after their period of authorized presence has expired.

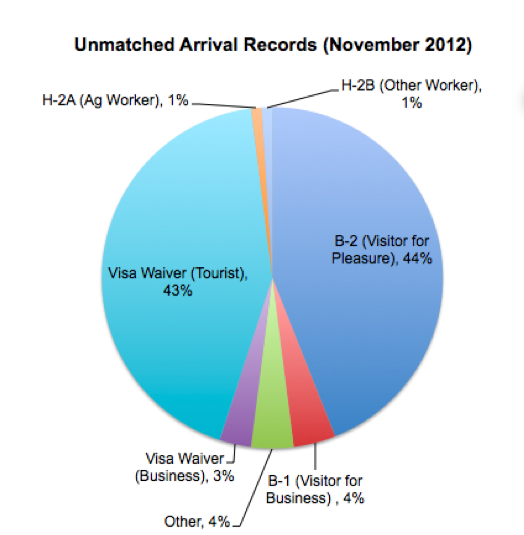

In July 2013, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) did just that. The GAO analyzed DHS records to assess the most common classes of admission for which DHS has no record of a departure despite a requirement to leave. As seen below, it found that lesser-skilled temporary workers—H-2As and H-2Bs who work seasonal jobs—each compose only roughly 1 percent of the total amount.

Assuming the proportion of overstays from land ports of entry is similar to the proportion from airports, just 99,440 of the estimated 11.3 million unauthorized immigrants were once lesser-skilled guest workers. The United States has admitted about 3.4 million H-2A and H-2B workers since 1988 when the programs began. Since there are about 4.7 million overstays in the United States, this means that about 97 percent of all H-2 admissions departed the United States as their visas require.

That number might be even higher for a couple of reasons. First, the 1 percent number from the GAO could be rounded up from 0.9 percent or even 0.6 percent (the report doesn’t say). If only 0.6 percent of overstays were H-2A or H-2B workers, that would mean that the overstay rate for these programs is just 1.8 percent (rather than 3 percent).

Second, a major caveat about using this method of estimating overstays is that it includes individuals who arrived at an airport, but who actually left through land ports of entry. My hunch is that seasonal workers are more likely to fit this description than other classes of admission. First of all, seasonal workers often travel to multiple worksites throughout the country away from their original entry point.

More significantly, H-2s are much more likely to be Mexican nationals, which means that they are much more likely to utilize a land port to exit. In 2013, for example, 93 percent of H-2As and 84 percent of H-2Bs were Mexicans compared to 53 percent of tourist visa holders and zero percent of visa waiver tourists (since Mexico is not a visa wavier country). In other words, it is very likely that lesser-skilled guest workers account for less than 1 percent of the total number of overstays, which means the percentage who overstay could be even lower.

Gov. Perry’s desire to keep guest worker programs from becoming a funnel for illegal immigration is warranted, but the available evidence indicates that the vast majority of foreign workers voluntarily comply with the terms of their visas. Foreign workers relish the opportunity to work legally in the United States and want to be invited back. By making legal immigration easier, we’d see even fewer foreign workers choose the black market over legitimate entry.

This post was updated.