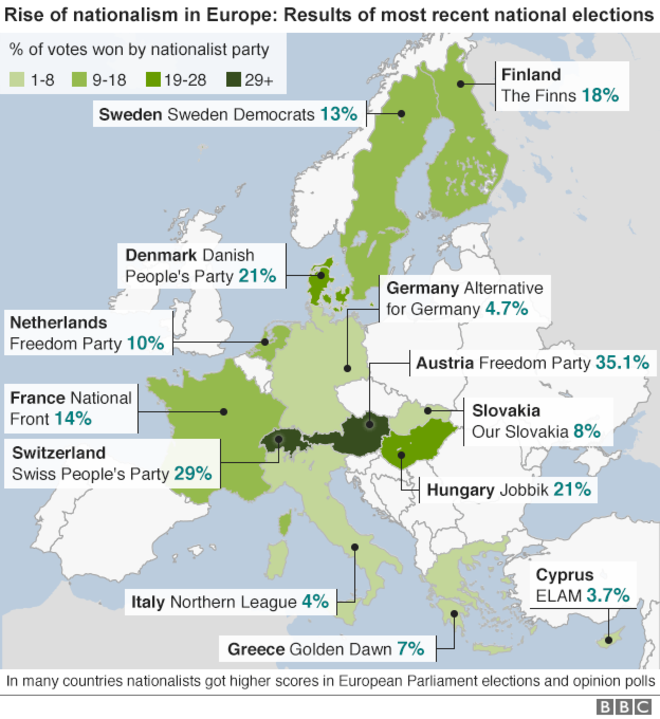

We are at what appears to be a rather troubling moment for liberalism. Authoritarian nationalistic movements are on the rise around the world. Liberalism, which looked like it had claimed a permanent victory in the market of ideas with the collapse of Communism has all of the sudden shown itself to be on far shakier ground than we might have thought. Nationalist movements had a head start in Europe, but America has shown that it is not immune to such impulses.

Like many of our political problems, this has proven to be a complex issue that is resistant to simple explanations. Some have blamed immigration, some have blamed weak economic growth, others have blamed economic inequality, and still others have blamed racial resentment. It is likely a fairly messy combination of a variety of these factors and some others that we haven’t thought of yet. But one thing that we can notice is that there is growing antipathy for our fellow citizens.

Factionalism and the Rise of Nationalism

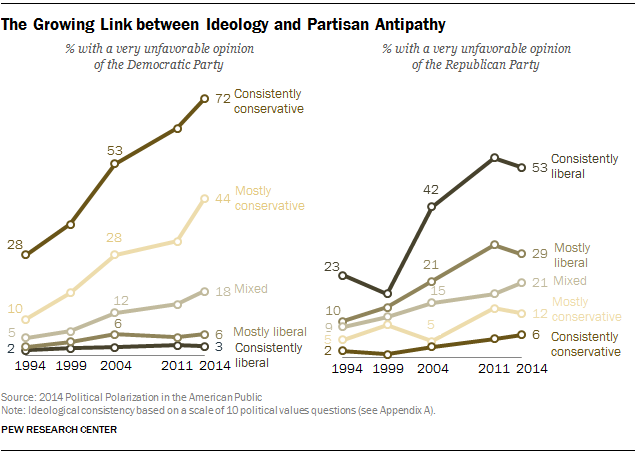

We have become more suspicious of our political rivals, and can indeed see them as threats to the nation’s well-being.

In the opening of Federalist 10, James Madison raises a worry that might sound familiar today:

Complaints are everywhere heard from our most considerate and virtuous citizens, equally the friends of public and private faith, and of public and personal liberty, that our Governments are too unstable; that the public good is disregarded in the conflicts of rival parties; and that measures are too often decided, not according to the rules of justice, and the rights of the minor party, but by the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority. However anxiously we may wish that these complaints had no foundation, the evidence of known facts will not permit us to deny that they are in some degree true. It will be found, indeed, on a candid review of our situation, that some of the distresses under which we labor have been erroneously charged on the operation of our Governments; but it will be found, at the same time, that other causes will not alone account for many of our heaviest misfortunes; and, particularly, for that prevailing and increasing distrust of public engagements, and alarm for private rights, which are echoed from one end of the continent to the other. These must be chiefly, if not wholly, effects of the unsteadiness and injustice, with which a factious spirit has tainted our public administrations.

Madison was addressing the concern of faction in politics. Madison offers this definition:

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.

Just as it was then, it is common now to hear complaints about factions, and a desire to put political parties and “special interests” aside and instead focus on what “the people” want. Madison, unlike some of his contemporaries who thought that smaller Republics would ensure less factious citizens, argued that factions were in fact inevitable. It’s too easy to confuse our self-interests with the general interest. It is too easy to make mistakes about the facts of the matter. It is too easy to see someone who disagrees with you as an opponent rather than a friend.

As long as the reason of man continues fallible, and he is at liberty to exercise it, different opinions will be formed. As long as the connection subsists between his reason and his self-love, his opinions and his passions will have a reciprocal influence on each other; and the former will be objects to which the latter will attach themselves. The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate, is not less an insuperable obstacle to a uniformity of interests. The protection of these faculties is the first object of Government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results; and from the influence of these on the sentiments and views of the respective proprietors, ensues a division of the society into different interests and parties.

The latent causes of faction are thus sown in the nature of man; and we see them everywhere brought into different degrees of activity, according to the different circumstances of civil society. A zeal for different opinions concerning religion, concerning Government, and many other points, as well of speculation as of practice; an attachment to different leaders ambitiously contending for preëminence and power; or to persons of other descriptions whose fortunes have been interesting to the human passions, have, in turn, divided mankind into parties, inflamed them with mutual animosity, and rendered them much more disposed to vex and oppress each other, than to coöperate for their common good. So strong is this propensity of mankind to fall into mutual animosities, that where no substantial occasion presents itself, the most frivolous and fanciful distinctions have been sufficient to kindle their unfriendly passions, and excite their most violent conflicts.

Madison was onto something. It’s true that factions are inevitable—we like being in groups (and favoring our in-group) so much that we’re willing to divide along almost any factional line. As a Red Sox fan I don’t quite trust Yankees fans, even if I’m assured that some are good people.

In lab settings, people are quite happy to help in-group members and treat out-group members unfairly, even if the groups are literally based on one’s estimation of the number of dots on a piece of paper. This group favoritism doesn’t need further explanation—no history of conflict, no long-term benefits from helping group members—we just like groups. Our group in particular.

For Madison, and indeed for most people, factions are organized around interests. And that does seem to be quite true. The NRA mobilizes around gun rights, the AARP mobilizes around social security and medicare and other interests of retirees, the Sierra Club mobilizes around environmental issues, and so on. Political parties are just more general-purpose versions of these different organizations: they cover a wider array of issues, but they are broadly coalitions that share (or come to share) common views and interests across a number of different areas of political life.

Simply understanding factions in terms of interests, however, misses an important part of the story. It is true that factions clash in part because of conflicting interests. But factions can also clash because they are, in some sense, talking past each other. It’s not just that they don’t agree about what to do with a particular issue, it’s that they disagree about what is at issue in the first place. Factions can come about for a variety of reasons, but importantly they can come into existence because people sincerely view the world in different ways, and bring different values to bear when they consider what is best for society.

Think of the fight around the Affordable Care Act. Democrats frequently spoke in terms of individuals having a right to health care. They viewed insurance programs that could charge women more money than men as fundamentally unfair, rather than a reflection of underlying actuarial costs of insuring men and women. They also pointed to health-related bankruptcies as being a significant source of financial instability.

Republicans, on the other hand, saw a law that mandated economic activity. They saw a new source of taxation on the wealthy. They saw an expansion of the welfare state—perhaps made most explicit by an increase in the size and scope of Medicaid. They saw an increased federal role in the regulation of a very large sector of the economy.

While all of these views make sense, they are talking about very different things. Republicans don’t need to take a strong position on whether there is a right to healthcare in order to reject laws that require that citizens participate in particular markets. After all, that looks like any other fight for broader market freedoms. Democrats don’t need to take a strong position on the degree to which the federal government should regulate markets to reject the unfairness of health insurance that costs more for women than men. After all, that looks like any other fight for eliminating discrimination against women.

In some sense, this is very different from how we usually think about political disagreement. Technocrats might think that there is optimal policy that we can deduce from looking at some combination of theory and empirical evidence. Before the evidence is in, we can debate about which mechanisms for achieving a particular goal are best.

But what we see in the debate about the ACA is that different factions saw it as being about different things. Not only did they disagree about what policy they should choose, but they disagreed about what kinds of evidence is relevant, what kinds of values are at play, and how those values are expressed or embodied by particular parts of the ACA.

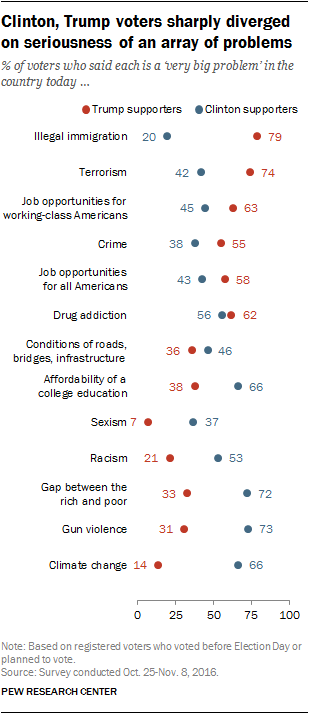

In our most recent election, we saw a version of this phenomenon as well. Trump supporters and Clinton supporters diverged not only on potential solutions to our problems, but what the problems were in the first place:

This sharp partisan disagreement about what is and is not a “very big problem” paints a bleak picture. It suggests that polarization is getting so bad that different factions literally see different countries. It is tempting to conclude that our diversity has made us ungovernable because we don’t share a common vision. No wonder why we don’t trust each other. No wonder why we have lost faith in liberal principles. Our diversity generated factions, and these factions are unwilling or unable to engage with each other in ways that allow us to make progress.

On this picture, fractious accounts of social identity heighten these underlying challenges. So-called “identity politics” increase the number of factions, increase the number of interests that our institutions are supposed to accommodate, and increase the points of contention. Making our diverse identities salient simply reminds us of our divisions.

If we accept this bleak picture, we immediately see reasons to attack “identity politics,” and perhaps to restrict immigration and do more to promote a common culture. After all, if our political problems are a result of factions, then we should aim to eliminate as many as we can.

I think this picture is a main source of the nationalist authoritarian impulse. Nationalism strives to achieve unity by means of suppressing or eliminating sources of diversity that might generate new factions. As Madison suggested, this can only be done with threats and violence.

Diversity Is the Solution, Not the Problem

If we are to renew liberalism, and demonstrate liberalism’s true strengths, then we need to recognize that diversity isn’t the source of our problems, but instead the source of our solutions.

There is a happier interpretation of our deep disagreements and our many different factions. Insofar as factions do really see the world differently, they become a true resource to our efforts at self-governance. As I argue in my new book, Social Contract Theory for a Diverse World, deeper, more fundamental disagreements are actually better for us than simply a disagreement between interests.

That we see the world through different perspectives is a wonderful thing, especially if we have any interest in improving ourselves and our societies. It’s for a very simple reason: we simply aren’t smart enough to think through complex problems on our own. There are too many different kinds of considerations, different sources of evidence, different kinds of values that we might want to bring to bear. No single perspective can capture all of that.

As the economist and philosopher Amartya Sen pointed out in his wonderful essay, “The Equality of What?,” even when we talk about seemingly straightforward values, such as equality, we can disagree about what counts as equal because there are so many different values that can be more or less equal, and we may differ on which to care about. We might care about equal outcomes, equal opportunities, equal voice, equal freedoms, or any number of other values. If you are a die-hard libertarian or egalitarian or utilitarian or whatever you might be, it’s likely that you are neglecting something important that your ideological opponent is tracking.

The most fundamental disagreements are the cases through which we can learn the most from one another. We simply can’t pay attention to everything at once—our brains are too small. But as a society we can divide our labor and attention and do just that.

One of Classical Liberalism’s greatest insights was in Hayek’s “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” Hayek writes:

The peculiar character of the problem of a rational economic order is determined precisely by the fact that the knowledge of the circumstances of which we must make use never exists in concentrated or integrated form but solely as the dispersed bits of incomplete and frequently contradictory knowledge which all the separate individuals possess. The economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate “given” resources—if “given” is taken to mean given to a single mind which deliberately solves the problem set by these “data.” It is rather a problem of how to secure the best use of resources known to any of the members of society, for ends whose relative importance only these individuals know. Or, to put it briefly, it is a problem of the utilization of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.

Hayek was focused on the role that markets play in drawing out hidden, private information to help society organize production. No single mind—no central planner—could determine how to optimally arrange a market. But the same insight can be straightforwardly applied to our politics. No single mind—nor a single perspective or faction—has enough knowledge about the way our society is organized such that they could optimally design our culture, our political order, or even simply our public morality.

The solutions to our very real problems are hidden in bits and pieces across all of the many different factions and perspectives that make up our societies. We ought, then, to be focusing on better ways of drawing from these disparate factions and taking advantage of our disagreements, so that we can together come up with better solutions.

As an example of this phenomenon, one of the great virtues of the Black Lives Matters movement—just as with every other important civil rights movement—is that it has helped the rest of the United States see a source of burdens that many of us were blind to. I do not have much interaction with the police in my life. So it is important to find out that for some communities, there are more outstanding warrants than citizens. Or that civil forfeiture and municipal fines make up sizeable portions of some local governments’ budgets. Or that some citizens are regularly stopped by the police without having done anything wrong. Or that police have extremely large leeway in their choices about using force.

For many of us, this wasn’t information that we had ready access to until it was brought to light by a political faction. Many of us did not suffer burdens from these policies, and so were largely unaware that such burdens existed for our fellow citizens. Despite our ignorance of what was happening, it was taking place in our names. We now have an ongoing debate about what to do in light of this knowledge.

Making Progress Through Disagreement

Liberalism asks a lot of us. We live in a very large country, and we find ourselves in wildly different circumstances.

For some, the Affordable Care Act was a lifeline. For others, it was yet another government intrusion. For some, the police are seen as protectors and community partners. For others, the police are seen as an occupying force and a source of harassment. For some, the language of “preferred pronouns” is yet another example of college campuses going too far. For others, it is gaining a bit of dignity and respect that is otherwise hard to come by.

These different experiences, and myriad others, bring out different values and different perspectives about how to go about improving the country. These will cause us to disagree. The liberal rules of an open society demand that we at least tolerate behaviors and values that we vehemently reject in our own lives. But tolerance by itself doesn’t quite get us to where we need to go.

Tolerance says we simply need to put up with the existence of those with whom we disagree. But at its core, liberalism demands that we engage with each other. John Stuart Mill, in his defense of the freedom of speech, argued that our interlocutors do us a favor when they disagree with us. Either they can show us why we are wrong, or they can help us to better understand why we are right. When we can learn that we are wrong, surely then our interlocutor has done us a true service. Likewise, if we have to develop new arguments to convince our interlocutor that he is wrong, we find out not just that we are right, but why we are right. Our interlocutor has helped us again.

Diversity and disagreement are hard. It is far more pleasant to be amongst friends who simply agree with us. It is easier to talk to someone who shares your values and sees the world in the same way. But it is much harder to learn from someone who agrees with you. It is much harder to improve, either as individuals or as a society, if we don’t have some of the frictions that are generated from disagreement. Diversity is an engine of progress precisely because it makes us agitated and dissatisfied.

What an open society demands of us, then, is that we accept this agitation in exchange for the far greater good of a dynamic society that provides room for all of us to pursue our own plans of life without imposing them on others. We don’t need to agree about everything, nor do we need to endorse those values that we find abhorrent. We simply need to recognize that all of us—all of our factions—have at best a partial picture. We can and should disagree with each other, but we should be aware that we can learn from each other as well. That we disagree isn’t a sign of bad faith, or of the other faction’s evil, but rather of evidence that we all have more work to do.

Diversity and disagreement aren’t the problems in our societies. They are the fuel that propel us forward. Liberalism’s strength is in recognizing this. Many of our liberal institutions are designed not merely to ease tensions between factions, but to leverage the competitive spirit brought on by these factions. Our job is not to quell the opposition, but to learn from them and to argue with them and struggle until we come up with new and better ideas.

—

Ryan Muldoon is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University at Buffalo and author of Social Contract Theory for a Diverse World: Beyond Tolerance.