Earlier this month, the New York Times published a report describing the Danish government’s controversial plan to demolish and relocate neighborhoods of low-income Muslim immigrants, which the government itself has dubbed “ghettos.” The plan is part of a recently passed initiative called “One Denmark Without Parallel Societies: No Ghettos in 2030” that also requires new immigrants to participate in programs designed to assimilate them into Danish culture, language and traditions. Attendance will be mandatory, even for children as young as 1 year old.

Reaction to the piece was predictable. Conservative commentators saw it as vindication for notion that “liberalism can only work in societies where there is broad consensus,” implying a tension between liberal democracy and multiculturalism, while commentators on the left called out Denmark’s current center-right government as racist and Islamophobic. The truth, as usual, is more complicated. Denmark’s immigrant enclaves, and the backlash they’ve engendered, aren’t the death knell for liberal democratic welfare states conservatives would like to believe they are. But it isn’t exactly rosy news for strong proponents of the Scandinavian model, either. Some types of social welfare are simply less compatible with multicultural immigration than others — a fact that Denmark is learning but many on the American left have yet to reckon with.

Public Housing Spurs Distributional Conflict

The culprit in the Danish case is clear: public housing projects. Not-for-profit housing makes up around 20 percent of Denmark’s total housing stock. While nominally managed as self-governing housing organizations with no income-test on membership, in reality the projects receive substantial government backing and are required by law to reserve up to 25 percent of rentals for vulnerable communities, such as refugees and the poor, unemployed, and disabled.

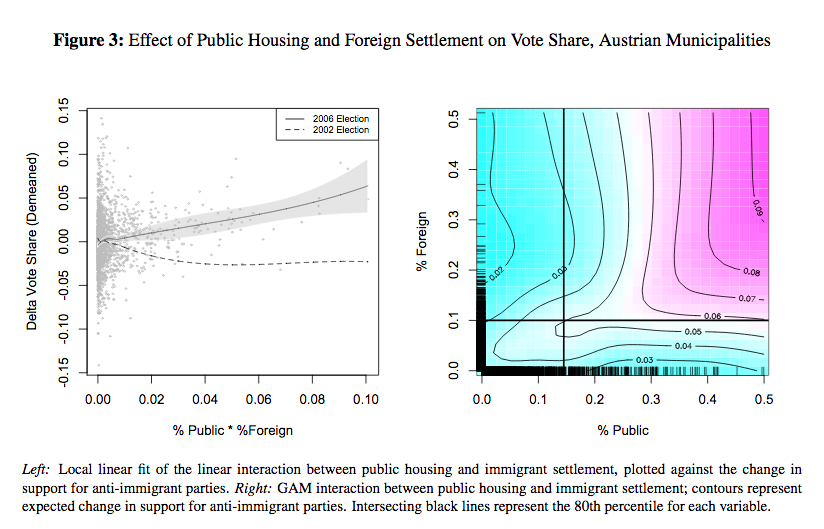

In their working paper, “How Distributional Conflict over Public Spending Drives Support for Anti-Immigrant Parties,” political scientists Charlotte Cavaillé and Jeremy Ferwerda argue that “in-kind” benefits like public housing are particularly prone to distributional conflict with natives due to their salience and scarcity. To test their hypothesis, they look at changes in anti-immigrant sentiment in Austria following a 2003 EU Directive that required member states to expand immigrant access to social services. At the time Austria finished implementing the directive in 2006, non-EU foreign residents who became newly eligible were equal in size to 7.7 percent of Austria’s total population, and approximately one-third of the population in public housing. Using the geographical densities of newly eligible immigrants and the public housing stock, Cavaillé and Ferwerda successfully model the subsequent increase in vote share for far-right political parties, finding that “the majority of increased support for the far-right in 2006 can be explained by public housing density.”

Public housing density predicts increased vote share for anti-immigrant parties in Austria.

By creating a salient, geographically segregated locus for native-immigrant conflict, Cavaillé and Ferwerda argue that public housing projects accentuate perceptions of scarcity, and thus activate zero-sum modes of thinking. As they write,

In-kind transfers are a class of social benefits for which supply is fixed in the short-term: building a new school or new public housing does not happen overnight and needs to be anticipated several years in advance. As a result, a population shock, such as a sudden inflow of immigrants, mechanically decreases per-capita benefit both in quantity (e.g. there are less slots available in existing schools) and quality (e.g. the average number of students per classroom increases). Because in-kind benefits are consumed locally and immigration is experienced locally, the environment is rich in informational cues that link a change in per-capita benefit to immigration. In contrast, the receipt and consumption of cash transfers is not geographically constrained and the existence of a distributional conflict between immigrants and natives is harder to infer from opaque and complex adjustments in the government’s budget.

These sort of congestion problems are a much smaller concern in economies where housing is privately developed and rented at market rates. Housing support that comes in the form of cash transfers or vouchers leaves the actual provision of housing to the market. Assuming no artificial constraints on development, markets do an excellent job of responding to population growth, as price increases create an automatic incentive for new construction.

The dynamic Cavaillé and Ferwerda find in Austria is clearly at play in Denmark, as well. The anti-immigrant Danish People’s Party (DPP) won 21 percent of the vote in 2015, making them the second largest party, and pulling the coalition of leading centre-right parties to the right. The DPP have been among the country’s loudest voices in favor of assimilationism, going so far as to propose using ankle monitors to enforce an 8:00 pm curfew on all so-called “ghetto children.”

As of December 2017, Denmark’s government classifies 22 of their housing projects as “ghettos,” defined as neighborhoods that meet at least three of the following five criteria:

- The unemployment rate exceeds 40 percent;

- The proportion of residents with non-Western background exceeds 50 percent;

- The number of residents age 18 and over with criminal violations exceeds 2.7 percent;

- The proportion of residents aged 30-59 without a basic education exceeds 50 percent;

- The average gross income for taxpayers aged 18-64 is less than 55 percent of the regional average.

One of the projects featured in the Times piece is called Mjolnerparken. Among its approximately 2,500 residents, 98 percent are either immigrants or born to immigrants, 82.1 percent are of non-Western origin (predominantly Palestinian refugees from Lebanon), 43.5 percent are neither employed nor in education, 2.52 percent have criminal convictions, 53 percent have only a primary education or less, and the average gross income is 51 percent of the regional average. A recent photo essay from Reuters photographer Andrew Kelly helps to capture the look and feel of Mjolnerparken, with its blocks of identical houses interspersed with the faces of alienated youth and armed Danish police patrols.

One need not endorse the Danish government’s hardline approach to understand why the ghetto system is in need of reform. By allowing low-income ethnic enclaves to form, public housing has not only emboldened the far-right. It has also genuinely retarded the integration of new immigrants. Although the far right in Denmark has sought more punitive measures, the essence of the current government’s plan involves increasing the number of native Danes who live in ghettoized communities, while privatizing the housing stock to introduce market incentives. An unenviable baseline to work from, it nonetheless provides useful lessons for policymakers in America.

Public Housing Redux

To many, the conclusion that public housing is prone to conflicts between natives and immigrants will seem obvious. And yet, whether it’s in the context of city-led “affordable housing” initiatives or in the national debate within the progressive movement, the romantic vision of large scale, government-financed housing projects lives on.

In an April report for the People’s Policy Project, Peter Gowan and Ryan Cooper propose solving America’s affordable housing shortage by “constructing a large number of government-owned municipal housing developments.” They propose combatting the segregation problem by opening the housing stock to “all income groups,” though with variable rent in order to price discriminate against richer tenants. They even cite Austria favorably, noting that “in Vienna, fully 3 in 5 residents live in municipal and cooperative social housing.”

As Democrats lurch to the left, the ostensible party of immigrants would be wise to avoid emulating the worst aspects of European democratic socialism, not least because such policies are fuel for the nativist right. To be sure, poorly integrated ghettos and an emboldened right-wing are not the outcomes leftists like Gowan and Cooper are hoping for. But they will be the result.

Migration Robustness

In previous blog posts and in my recent paper, The Free-Market Welfare State, I argue defenders of the welfare state must take seriously the issue of “migration robustness” when thinking about policy design. Specifically, I argue that there are three key parameters to making social systems robust to large scale immigration:

- Prior contributions. When social insurance schemes, like Medicare or Social Security, are funded in part or in whole by prior contributions through payroll taxes or associated fees, the real and perceived fiscal cost of low-skilled immigration is greatly attenuated.

- Universality. While highly means-tested benefits have better targeting on the needy, they also create a conspicuous class of “takers” that feed public resentments. This is particularly the case when recipient populations are identifiable according to other salient traits, such as language or ethnicity. While universal social programs may be more expensive, they avoid creating a “parallel society” where different rules apply.

- Market Flexibility. Markets do a good job of responding to the increased demand for goods and services created by population growth thanks to the role rising prices play in incentivizing new supply. Social welfare systems that rely heavily on “in-kind” benefits (as opposed to direct cash transfers or vouchers) are comparatively supply-inelastic, which creates conflict during waves of immigration.

As the Danish and Austrian cases suggest, this last parameter — the flexibility of the market and the fungibility of cash — is arguably the most important. Although my writing usually focuses on persuading conservatives that social insurance and the market are compatible, it’s just as important for progressives to realize that market mechanisms are not the enemy of social justice, either. On the contrary, a freer market can help to advance progressive causes, including the fluid integration of immigrants into housing and employment, and in a way that minimizes fights over zero-sum resources.