Medicare for All has become a core campaign issue for Democratic candidates this year. They just might win with it. The concept polls well. According to recent data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, 59 percent of Americans say they favor “having a national health plan, or Medicare-for-all, in which all Americans would get their insurance from a single government plan.”

But, suppose the dog catches the bus. What then? Adam Green, co-founder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee, points out that one of the things that makes Medicare for All work so well as a campaign slogan is its “pleasant ambiguity.” For some, it means a comprehensive plan like that proposed by Bernie Sanders (overview, draft legislation), in which everyone would get first-dollar coverage from a single government agency. For others, it means something much more modest, like adding a government option, modeled on Medicare, for people who buy health insurance on the Affordable Care Act exchanges. For still others, it means something in between.

Sooner or later, Democrats are going to have to start thinking about how to implement Medicare for All if they win. Fortunately, there is a practical and affordable way of doing so that would protect everyone from ruinous medical bills, ensure that everyone pays their fair share, and makes health care transparent, efficient, and consumer-friendly. Read on.

What we can we learn from other countries?

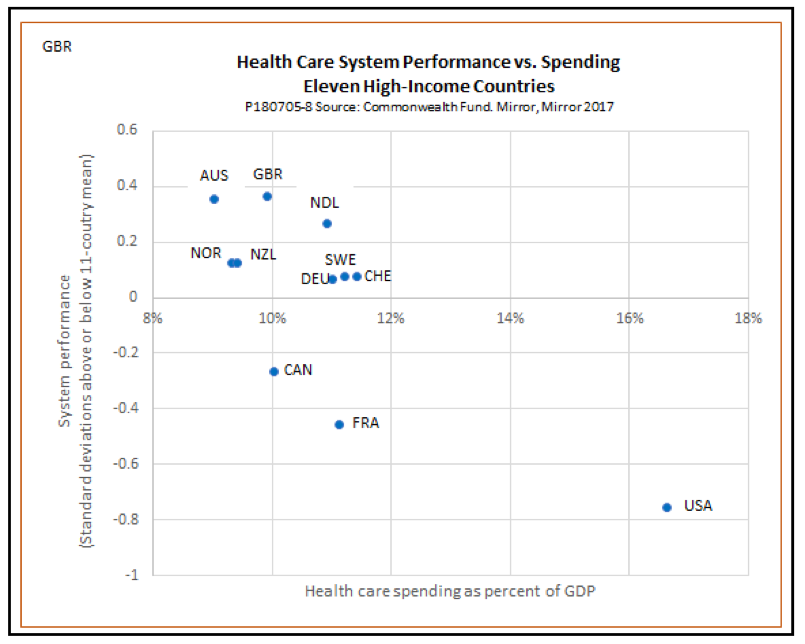

Many supporters of universal health care seem to think that all we Americans need to do is copy the kind of single-payer system that other rich democratic countries already have. There is an element of truth to that. In many ways, U.S. health care falls far short of what other countries provide. In fact, an often-cited international comparison from the Commonwealth Fund, summarized in the following chart, places the United States dead last among 11 high-income countries in terms of health care performance in spite of the fact that we spend a lot more than anyone else.

What’s going on here? Is there something that the health care systems of all those other countries have in common, something that we can learn from? Yes. Is that something a single-payer model like the Sanders version of Medicare for All? Not really.

Let’s look at a few examples, starting with the best. The Commonwealth Fund assigns the highest performance ranking among the 11 systems covered in its survey to the British National Health Service (NHS). The NHS provides a wide range of services without charge. Many doctors, but not all, are NHS employees, and many, but not all, clinics and hospitals are owned by the government. However, the NHS is not a pure single-payer system.

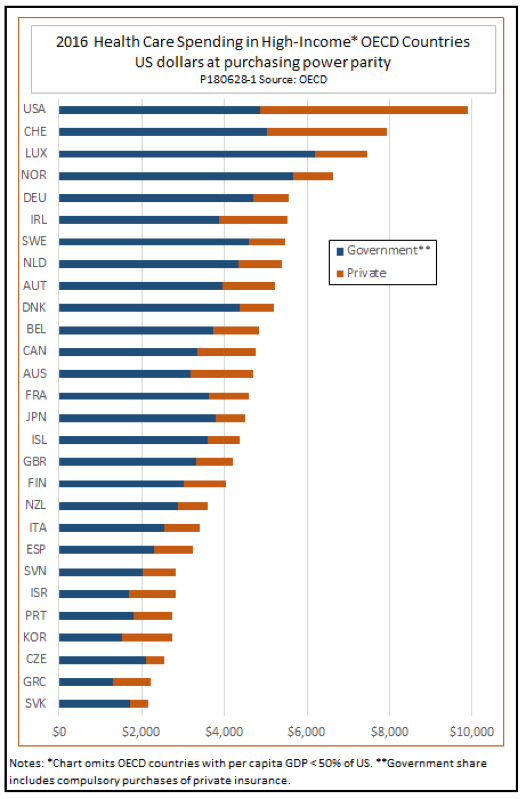

For one thing, the NHS is much less centralized than many Americans realize. Its English, Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Irish services operate with considerable autonomy. Within the English NHS, administration and policy are further decentralized into more than a hundred NHS Trusts. Furthermore, the NHS does not pay for everything for everyone. For example, it requires most people to make copayments for prescription drugs and dental care, although charges are waived for people who cannot afford them. The U.K. also has a small but flourishing private health care sector that caters to people who choose not to use the NHS. All in all, the government pays 79 percent of all per-capita health care expenses — much more than in the United States, but only the twelfth-highest percentage among the countries shown in the next chart.

Australia, ranked second-highest in performance by the Commonwealth Fund, has a different kind of system. The Australian federal government provides much of the financing, but it plays a more limited role than the British NHS in the actual delivery of services. Additional funding comes from state governments, which are responsible for public hospitals, ambulance services, mental health, and some other services. Local governments provide community and preventive health services. Out-of-pocket payments account for 18 percent of total health care spending. Nearly half of the population has supplemental private insurance to help cover deductibles and copays, and to get shorter waiting times and a greater choice among providers. Government at all levels covers 68 percent of total health care spending.

The Netherlands, ranked third by the Commonwealth Fund, has a different system still. It covers about the same share of total health care costs as the U.K., but it is even more decentralized. Rather than having a single national insurance fund, the Dutch system relies on mandatory purchase of private health insurance. Coverage and premiums of the private policies are closely regulated. Tax-financed subsidies keep premiums low, but some services are subject to deductibles and copays. Additional subsidies are available to people with low incomes, so that coverage is kept affordable for everyone. Most people also purchase supplemental insurance to cover items not in the basic package (dentistry, eyeglasses, and contraceptives, among others), and also to cover deductibles and copays.

The other countries covered by the Commonwealth study use variants or hybrids of the three models represented by the U.K., Australia, and the Netherlands. (See this useful site for detailed national profiles.) None of them has a true single-payer system, whether we use that term to mean one that centralizes health care finance in a single government entity or one that covers all costs for everyone.

So, if not a single-payer model, what do other countries have in common that earns them such high ratings? The answer is, they all have universal affordable access to basic health care. Universal affordable access, then, is the goal that we should focus on if we want America to join the club. Once we commit to that, we are ready to think about designing a system that borrows from the best practices of others while recognizing unique American circumstances.

Paying a fair share

Let’s start with the need for everyone to pay a fair share. Committing to universal affordable access necessarily means committing to a system in which the rich pay more than the poor, but not one that makes every household responsible for all its own members’ medical expenses. Even if health problems were distributed randomly, many poor households and some in the middle class would experience medical expenses that exceeded their entire incomes. The fact that people with lower incomes tend to have more health problems makes the problem of affordability even worse.

Private insurance is not enough, by itself, to solve the problem. Too many health conditions are commercially uninsurable. Insurability requires that risks be due to unpredictable chance, but lifetime care for chronic conditions like diabetes and risks determined by genetic factors are not unpredictable. Actuarially fair premiums for such pre-existing conditions would bankrupt the insured, while lower-than-actuarially-fair premiums would bankrupt the insurers.

One way to handle the problem of uninsurability is to redistribute the burden of health care costs through taxation. For example, the Sanders version of Medicare for All envisions a 6.2 percent tax on employers, a 2.2 percent income-based premium for individuals, increased personal income tax rates for high-income households, and higher taxes on dividends and capital gains.

The tax-based approach is conceptually workable, but it is not the only option, or the best one. An alternative, universal catastrophic coverage (UCC), uses income-based deductibles, rather than new taxes. UCC interprets the principle that everyone should pay a fair share, but not more, to mean that people should never have to forgo medical services because they cannot afford them, but when they can, they should pitch in.

Universal catastrophic coverage is entirely consistent with the overall concept of Medicare for All. Under a UCC version of that plan, everyone would automatically be issued a policy similar to a conventional Medicare or Medicare Advantage policy, with no premium required. For families below a designated low-income threshold, for whom almost any medical expenses would be unaffordable, the deductible would be set at zero. For others, the deductible would be set as a percentage of eligible income, that is, of the amount by which household income exceeds the low-income threshold. For everyone, regardless of income, deductibles would be waived on a package of basic primary and preventive services, such as prenatal care and childhood vaccinations.

For example, suppose the low-income threshold were set at the federal poverty level, currently about $25,000 for a family of four, and the deductible at 10 percent of eligible income. In that case, a family with income of $25,000 or less would have first-dollar coverage with no deductible. A middle-class family with $75,000 of income would have a deductible of $5,000, comparable to the out-of-pocket costs of an ACA silver plan (but without the monthly premium). A wealthy family with an annual income of $1 million would have a deductible of $97,500, which they might decide to cover, in part, with some form of supplemental insurance.

Medicare for All with income-based deductibles would still require a substantial amount of financial support from the federal government. However, careful cost analysis suggests that such a program could be fully funded using money that the federal government already spends on health care through the ACA, Medicaid, conventional Medicare, and the tax expenditures that subsidize employer-sponsored insurance. No new taxes would be required at the federal level. States could choose to sweeten the basic federal program with their own funds if they wanted, for example, by raising the low-income threshold above the federal poverty level or by reducing deductibles.

Which way is better?

In principle, the tax formulas of a Sanders-type Medicare for All plan and the parameters of a UCC version (that is, the low-income threshold and deductibles) could be tweaked to produce exactly the same average burden on households at each level of income. In that sense, neither version is inherently more “progressive” than the other. However, even if the two plans distributed the burden of health care costs the same way among income groups, there are two reasons to prefer the UCC approach.

One is that using deductibles rather than taxes to achieve a fair distribution of the economic burden of health care would help to control administrative costs, which are one of the major factors dragging down the performance of the U.S. system in the Commonwealth study. A plan like Sanders’ would have to collect billions of dollars in taxes from wealthy Americans and would then give a large part of that right back to them in the form of health care benefits more generous than those found anywhere else in the world. Doing that would be a colossal waste of administrative efforts.

Taxation is, notoriously, a “leaky bucket.” Administrative costs both of collecting taxes and of disbursing proceeds mean that the net burdens of tax-financed programs are always greater than their effective benefits. Taking into account indirect economic effects, such as the possible adverse effects of new taxes on jobs and wages, makes the picture even less favorable. It is best to limit taxpayer financing to public services that cannot reasonably be paid for any other way. Essential health care for the poor and protection against catastrophic medical bills for the rest fall into that category. Routine health care expenses for financially secure families do not.

Income-based deductibles would further save administrative costs by simplifying the payment process. Until a family meets its deductible, it pays the provider for care directly. UCC authorities only need to get a copy of the bill in order to keep a tally of the family’s progress toward meeting its deductible. The government gets directly involved in payments only after the deductible is met. The extra staffing that doctors and hospitals now need to deal with multiple insurers, each with its own unique administrative requirements, would be greatly reduced.

Incentives for greater transparency and more careful health care shopping are a second point in favor of deductibles. Consider, for example, the case of MRIs, as discussed in an article in Health Affairs by Sze-jung Wu and associates. The study notes that the cost of an MRI can vary from as little as $300 to as much as $3,000 within a given area, with prices tending to be higher at hospitals than at free-standing imaging centers. The authors report the results of a real-world controlled experiment in which some patients participated in a price transparency program that allowed them to compare various imaging providers in their area. The study found that patients in the price transparency program spent significantly less per MRI than those in the control group. The experiment also observed a tendency for high-cost providers to reduce their prices in areas where the transparency program was operative.

Even under a UCC version of Medicare for All, not everyone would be responsive to economic incentives. Some people who needed an MRI or other procedure would have low incomes and no deductibles; some would have already met their deductibles or would expect to meet them regardless; some would be too stressed by their health problems to shop around; and some might simply not care. However, much the same can be said about transparency and price incentives in a supermarket. Not everyone shops carefully for breakfast cereal, but for every shopper who just reaches for their favorite brand, another carefully compares the price-per-ounce tags and looks for items on sale. Even if comparison shoppers are a minority, their behavior puts competitive pressure on cereal makers to keep prices down. Indirectly, that benefits even the grab-the-nearest-box types.

Although market incentives would help keep prices down, they might not be enough in themselves. They would work better if a Medicare for All plan, whatever its form, included a full range of administrative cost control measures. For example, plan administrators could encourage “bundled payments,” so that providers would get a set amount, say, for a knee replacement rather than billing separately for each X-ray and saline bag. They could require providers to post prices in an easily searched format and supplement the price data with information on quality. They could encourage the use of nonphysician providers for cases that do not require the full skills of an M.D. They could implement reforms that reduced incentives for practicing wasteful defensive medicine. They could use their purchasing power to bargain for favorable prices from drug companies. The list of possible cost control measures goes on and on.

Looking beyond the campaign

As we said at the outset, Medicare for All could play well for Democrats. During the campaign season, the “pleasant ambiguity” of the idea could actually be an advantage. Votes are more likely to turn on the broad goal of affordable access to health care for everyone than on wonky administrative details and program parameters.

Behind the scenes, though, someone is going to have to think ahead. Viewed pragmatically, rather than as a campaign slogan, a comprehensive, single-payer version of Medicare for All has its drawbacks. Taxing the rich and then giving them back their money in lavish health benefits is administratively inefficient. Full first-dollar coverage for everyone would mean that regulatory measures alone would bear the full burden of cost control, without the added push of market incentives. The new taxes required to fund single-payer legislation would create daunting political hurdles.

Those drawbacks are among the reasons that no other country has a true first-dollar, single-payer health care system. The plain fact is that implementing something like the Sanders version of Medicare for All would not mean learning from the experience of other countries, but rather, rejecting their experience.

Many policy analysts on the left also recognize these realities. For example, the influential Center for American Progress has recently released its own detailed health care plan, which it calls Medicare Extra for All. The CAP’s plan aims to take the best features of Sanders’ version and give them a more realistic financial foundation. Medicare Extra differs in several respects from the UCC-type plan we have described here, but there are also substantial similarities, including a guarantee of full first-dollar coverage to people with low incomes and a sliding scale of deductibles and other out-of-pocket payments for those who can afford them. (See this earlier post for a full side-by-side comparison.)

By all means, then, candidates should campaign on Medicare for All, with all of its “pleasant ambiguities,” if that is what it takes to win elections. Then, when it comes time to turn slogans into policy, focus on the pragmatic goals of protecting everyone against the threat of ruinous medical expenses, ensuring that everyone pays their fair share of the cost, and making health care transparent, efficient, and consumer-friendly.