Universal catastrophic coverage (UCC) is a health care plan that aims to protect all Americans against financially ruinous medical expenses, while preserving the principle that those who can afford it should contribute toward the cost of their own care. It offers a potentially attractive compromise between the current system, which leaves millions of people uninsured or underinsured, and more expensive, “first dollar” proposals that would cover all health care costs for everyone.

Skeptics often ask whether such a plan is affordable. The short answer is “Yes,” but I would prefer to frame the question differently. Rather than asking how much any given health care plan would cost, it is more useful to ask, “What is the best plan we could design for what we are politically willing to spend?” If we set that amount somewhere close to what the government now spends on health care, universal catastrophic coverage looks rather good. This post explains why.

The parameters of universal catastrophic coverage

First, we need to review the basic parameters that define any UCC plan. The simplest version of UCC would have just two parameters, a low-income threshold and, for those above the threshold, a deductible that varies with household income.

The low-income threshold is a level of income below which any medical expenditures at all threaten serious financial distress. Under UCC, people whose incomes are at or below the threshold would need to be covered in full. The dollar value of the low-income threshold would vary with family size. Some versions of UCC simply set it equal to the federal poverty level (FPL), which, as of 2018, stands (in round numbers) at $12,000 for an individual and $25,000 for a family of four.

Given a low-income threshold, the deductible can be set as a percentage of eligible income, that is, the amount by which household income exceeds the threshold. For example, if the deductible is 10 percent of eligible income and the low-income threshold is the FPL, a family of four with total income of $50,000 would have eligible income of $25,000 and a deductible of $2,500. A family with total income of $100,000, which would put them at the upper limit of eligibility for premium subsidies on the ACA exchanges, would have a deductible of $7,500 — a little less than their deductible under a typical ACA silver plan. A family with total income of $1 million would have a deductible of $97,500, and so on. For administrative purposes, household income could be defined as adjusted gross income reported on the previous year’s tax return, perhaps with some form of averaging for those with highly variable incomes.

Some versions of UCC include copayments as well as deductibles. For example, we could set the low-income threshold at the FPL and the deductible at 5 percent of eligible income, and then add a copay of 20 percent on health care expenses from 5 percent to 30 percent of eligible income. A family of four with eligible income of $50,000 would then face a deductible of $2,500 and a 20 percent copay on expenditures from $2,500 to $15,000. Its out-of-pocket maximum, consisting of the $2,500 deductible plus $2,500 in copays, would be the same as under a UCC plan with a 10 percent deductible and no copay.

Some UCC plans also include a premium, which would be paid whether or not the family had any health care expenses in a given year. Typically, the premium is zero for people below the low-income threshold and follows a sliding scale for people with higher incomes. A family’s maximum total contribution to its health care expenses would then be the sum of its deductible, its copays, and its premium.

Finally, many versions of UCC specify a package of preventive services that would be exempted from deductibles and copays. If the package were limited to highly cost-effective services, it could reduce total out-of-pocket costs to insured households with little impact on the cost of the program to the government budget, since the cost of vaccinations, screenings, and the like would be largely, or even wholly, recouped through reductions in the cost of treatment of preventable conditions.

Trade-offs among the parameters

Each of the five parameters of a UCC plan — the low-income threshold, the deductible, the copay, the premium, and the preventive package — serves a particular objective. Tightening or loosening any one parameter lowers or raises the cost of the plan. By trading off the tightening of one parameter against the loosening of another, it is possible to emphasize one objective and de-emphasize others while holding the overall cost of the plan constant. With that in mind, let’s look at each of the parameters in turn.

The low-income threshold. Other things being equal, a higher threshold increases the budgetary cost of a UCC plan. That, in turn, creates pressure to control costs elsewhere, for example, by imposing higher deductibles and copays on middle- and upper-income households. For budgetary purposes, then, it would make sense to set the threshold at the lowest level that is consistent with the basic purpose of UCC, which is to ensure that no one is exposed to financially ruinous medical expenses.

For the sake of discussion, many treatments of UCC set the low-income threshold equal to the FPL. However, the FPL is not especially well-suited for this purpose. Historically, the FPL, which dates from the 1950s, was based on the assumption that a family with income equal to three times the minimum needed for food would be able to provide adequate nutrition with enough left over for other necessities. At that time, however, health care prices were much lower, relative to those of food, shelter, and clothing, than they are now. The higher cost of health care services in today’s economy would argue for setting the low-income threshold for a UCC plan somewhat higher than the FPL, perhaps at the 138-percent-of-FPL that is used to determine Medicaid eligibility in states that chose to expand the program under the ACA.

Deductibles. Under UCC, deductibles serve a threefold purpose. First, they limit the budgetary cost of the plan in comparison with alternatives that would provide first-dollar coverage for everyone. Second, they uphold the principle that people who can afford to do so should assume responsibility for their own non-catastrophic health care expenses. And third, they give health care consumers “skin in the game,” which, according to advocates of market-based health care, should make them better shoppers who carefully compare the cost and quality of services and budget prudently to meet foreseeable medical expenses.

These three considerations lie behind the growing popularity, not just of UCC proposals, but of high-deductible health insurance of all kinds. Unfortunately, though, there is a downside to high deductibles: In practice, people are not always as prudent in their health care choices as they might be.

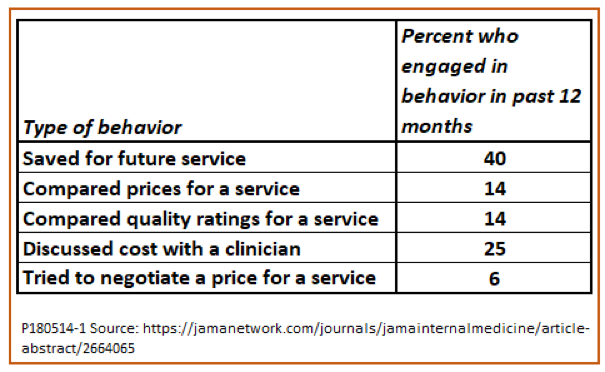

For example, a recent study by Jeffrey T. Kullgren and colleagues looked at the behavior of a large sample of health care consumers with high-deductible policies. Their findings, summarized in the following table, indicated that only 40 percent of respondents had saved any money toward the cost of future services, even though some 58 percent of respondents had set up health savings accounts. Only a small minority of those surveyed attempted to compare price or quality of services. And, although a quarter of respondents discussed price with providers, only six percent actually tried to negotiate prices.

Attempts by consumers to learn more about price and quality or to negotiate prices, when they were made, produced mixed results. Among consumers who engaged in at least one of these behaviors, 26 percent decided to put off the service until they could afford it, 10 percent decided that the service was not worth the cost, and 22 percent managed to obtain the service at a lower price. Only the last of these outcomes is unambiguously good. Postponing or forgoing a service because of its price is a good outcome if it deters the consumer from using a service that is not cost-effective, but not if the service has benefits that exceed its costs. Other research has found that consumers are often poor judges of cost-effectiveness and forgo both appropriate and inappropriate services for reasons of affordability.

Copayments. In principle, copays serve the same three purposes in a UCC plan as do deductibles. However, the two are not fully interchangeable, since copays have special advantages and disadvantages of their own.

On the positive side, copays extend the range of expenses over which consumers have an incentive to shop for the best health care values. Compare, for example, two versions of UCC, each of which imposes the same $5,000 maximum out-of-pocket cost on individuals with eligible income of $50,000. Plan A has a straight $5,000 deductible and no copays, while Plan B has a $2,500 deductible and a 20 percent copay on expenses from $2,501 to $15,000.

If I have Plan A, then once my medical expenses pass $5,000, I pay nothing for further services. According to the “skin in the game” theory, I will have no incentive to avoid services that are not cost-effective or to look for the lowest prices for those that are. In contrast, under Plan B, I would have an incentive to be a good health care shopper until the cost of my care rose all the way to $15,000, even though my own maximum exposure would be no higher than under Plan A.

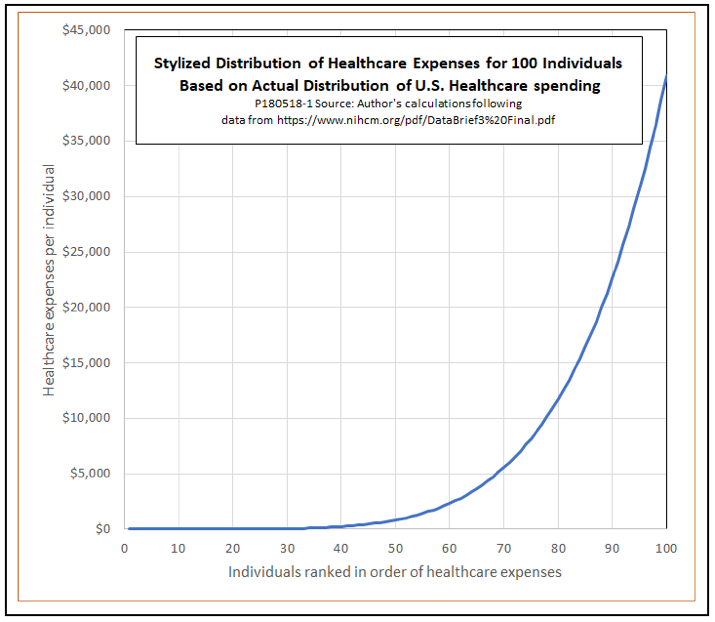

However, copays also have their drawbacks. One is that for a given out-of-pocket maximum, a UCC plan with copays would be more expensive for the government to operate. To see why, suppose that our Plans A and B were applied to 100 individuals, whose health care spending was distributed according to the pattern shown in the following chart. As in the actual distribution of health care expenses for the U.S. population, this stylized distribution of spending is highly skewed. The average is $10,000 per person, but a third of the population spend less than $100 each, while the top 20 percent of individuals account for more than 80 percent of the total.

Those who spend less than $2,500 (60 percent of the population but only 3.5 percent of total spending) would not meet their deductibles under either Plan A or Plan B, and all those with spending of more than $15,000 would hit their out-of-pocket maximums. For both of those groups, out-of-pocket expenses would equal to total expenses. However, people with expenditures between $2,500 and $15,000 (22 percent of the population and 25.9 percent of all spending) would have lower out-of-pocket costs under Plan B, where they are in the copay range, than under Plan A.

When you do the numbers, it turns out that the budgetary cost of Plan B would be 7 percent greater than that of Plan A. To bring the government’s cost for the plan with copays down to that of the plan without them, we would have to allow a larger out-of-pocket maximum for Plan B than for Plan A, either by raising the deductible for Plan B, or extending the copay range, or both.

True, this comparison assumes that people’s actual health care expenses remain the same under Plan A as under Plan B. That would not be the case if, as intended, both deductibles and copays induce consumers to shop for better prices, or to forgo services that they perceive as unaffordable or not cost-effective. A more complete comparison would have to take into account elasticities of demand for services with respect to deductibles and copays. It is not clear a priori which of these two plans would have the stronger effect on health care spending or which would produce better health outcomes. Case studies of the effects of specific policy changes result in disparate findings.

A full comparison should also consider the relative administrative burdens of copays and deductibles. In a plan with deductibles only, any given service is either billed entirely to the patient or entirely to the insurer. With copays, there is an extended range of expenditure over which bills must be split, with the patient and the insurer each paying part. Based on the distribution of expenditures in the chart, that range covers more than a quarter of all health care spending. Within it, the extra paperwork and collection expense raises billing- and insurance-related-costs for doctors, insurers, and patients.

Preventive care. As explained in an earlier post, the risk that people will forgo cost-effective preventive services can be reduced by exempting those services from deductibles and copays. In some cases, such as childhood immunizations, doing so will actually decrease total national health care costs. Even when it does not, there are many cases in which the payoff to preventive care is large compared to its cost. As a starting point, a UCC could simply adopt the package of preventive services currently offered free of charge under the ACA. However, as Mark Pauly and colleagues explain in an article in Health Affairs, there is a lot of room for improvement in the current system for measuring cost-effectiveness.

Premiums. The final major parameter of a UCC plan is the premium, if any, to be paid by policyholders. Like deductibles and copays, premiums are motivated by the idea that people should pay a fair share of health care costs when they can afford to do so. Within a given cost to the government budget, adding premiums to a UCC plan would make it possible to reduce deductibles or copays. However, the distributional and incentive effects of premiums are quite different from those of deductibles and copays.

To be consistent with the goal of making coverage affordable to everyone, premiums, like deductibles and copays, would need to vary with income and to be waived for households below the low-income threshold. As a result, premiums would not have much effect on the distribution of health care costs according to income. Instead, the main effect of adding a premium to a UCC plan would be to redistribute health care costs toward people who are healthy and away from those who are ill within specific middle- and upper-income groups. If we view taxpayer-funded health care as a form of social insurance, that makes sense.

The downside is that introducing premiums might improve perceived fairness at the expense of incentives for more careful choice by health care consumers. A premium, once paid, is a sunk cost that has no effect on people’s decisions to visit their doctors or to wait to see if they feel better in the morning, nor do premiums provide any incentive to shop for the best price for a knee replacement rather than simply visiting the closest hospital.

Premiums also raise difficult issues regarding universality of coverage. With no premiums, there would be no problem with automatically enrolling everyone for UCC coverage. Some people might decline to use their policies even if they developed health problems, perhaps on religious grounds or perhaps because they are just too stubborn to spend anything on health care even when they need it. That would be up to them. But introducing a premium requires deciding what to do about people who fail to pay it. Are you going to turn them away at the emergency room door? Are you going to let them play the free rider, and later pay up and join the system when they become ill? Are you going to seek court orders to garnish their wages?

If you kick out people who don’t pay their premiums, then coverage is no longer universal. If you don’t kick them out, you open the door to free riders. If you collect the premium by force of law, then it is not a premium, but a tax. And to the extent you are going to finance UCC with taxes, it is arguably better to do so out of general revenue than through a special health care tax that you euphemistically call a “premium.”

Estimating the cost of universal catastrophic coverage: A case study

So far, we have looked at the economics of UCC in the abstract. This section turns to the challenging issue of estimating the actual dollar cost of a specific UCC plan.

To date, the most ambitious attempt to do so is one by Jodi L. Liu of the RAND Corporation. Liu uses a detailed simulation model that includes population data, estimates of demand elasticities, and estimates of additional cost-saving measures, all drawn from reviews of the literature. She applies the model to two different national health care plans: a 2013 version of Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All proposal and a UCC plan outlined in 2012 in National Affairs by Kip Hagopian and Dana Goldman.

For purposes of estimation, Liu sets the parameters of the catastrophic plan as follows: The low-income threshold is 100 percent of the FPL. The deductible is 10 percent of eligible income. Copays are 5 percent, subject to an out-of-pocket maximum of 14.5 percent of eligible income. Given these parameters, households thus hit their out-of-pocket maximum at the point where health care expenses reach 100 percent of eligible income. Liu also assumes a fixed charge, waived for incomes up to FPL and assessed on a sliding linear scale up to a maximum of $3,350 at 300 percent of the FPL. She calls this charge a “tax,” although Hagopian and Goldman themselves, writing in Forbes, call it a “premium.” Liu does not model the cost of a package of free preventive services, even though the original Hagopian-Goldman plan that she draws on recommends such a feature.

The basic version of the UCC plan that Liu considers leaves Medicaid and Medicare intact, and covers everyone who does not participate in either of those programs. As such, it completely replaces all employer-sponsored insurance. She also considers variants that preserve employer-sponsored plans as optional alternatives.

Liu estimates that for 2027, the basic UCC plan would reduce total national health care expenditures by $211 billion, or about 8.7 percent. She estimates that total federal expenditures on health care would increase by $648 billion compared with expenditures under the ACA for that year. Of that increase, $524 billion would be covered by revenue from the dedicated tax/premium. The remainder would be slightly more than offset by increased revenue from income and payroll taxes due to elimination of the deduction for employer-sponsored insurance. As a result, the net impact of the basic UCC plan on the national budget would be a saving of $40 billion.

For comparison, Liu estimates that Sanders-style first-dollar coverage would increase total national health care expenditures by 18 percent and federal health care expenditures by 60 percent. Most of the additional federal spending for the Sanders plan would come from new taxes.

Next, Liu estimates potential savings in administrative costs for insurers and providers, together with further savings from negotiation of better prices for prescription drugs, hospital services, and other provider services. The net effect, with the further cost savings, would be a reduction of total national health care expenditures by $767 billion dollars, or 35 percent.

Although some of the $767 billion of further savings in national health care expenditures would accrue to individuals, Liu estimates that $556 billion of those savings would accrue to the federal budget. Including the further cost savings, then, total impact of the basic UCC plan on the federal budget would be a net saving of $596 billion, rather than the $40 billion estimated for UCC without further cost saving. Note also that the federal share of further cost savings of $556 billion is slightly greater than the estimated $524 billion of revenue that would be raised by the tax/premium feature of the basic UCC plan. Putting this all together, then, total federal expenditures on health care would be $72 billion less than under the ACA even if the tax/premium were dropped from the plan.

Liu’s estimates are carefully constructed and draw on the best available data. Nonetheless, they should be considered as illustrative, not as definitive. Further research might reach different conclusions regarding the responsiveness of health care consumers to system changes, the success of cost control efforts, and changes in tax revenues. Other investigators would doubtless want to explore the effects of changes in various UCC parameters, and to examine a broader UCC plan that replaced Medicaid and/or Medicare. Still, UCC proponents will find Liu’s estimates encouraging, since they are consistent with the expectation that a reasonable UCC plan could be implemented without new taxes or large increases federal health care spending.

Conclusion: Optimizing for health

This brings us back to our original question: Could we afford a national system of universal catastrophic health coverage? I think the answer is yes. Within the limits of what the government now spends on health care, it appears reasonable to suppose that we could afford a UCC plan with a low-income threshold at or a little above the federal poverty level; an out-of-pocket maximum (including deductibles and copays) in the range of 10 to 15 percent of eligible income; a package of exempt preventive services similar to that offered under the ACA; and no individual premium or new dedicated taxes.

That general outline of a UCC plan leaves many questions open. To list just a few, what combination of deductibles and copays would produce the best balance between incentives to shop carefully and the tendency of participants to forgo appropriate, cost-effective care? What kinds of reform could provide better information about health care prices and quality in order to facilitate consumer choice? What kinds of savings vehicles or supplementary insurance products might be useful to help middle- and upper-income consumers with out-of-pocket costs? What would constitute an appropriate package of exempt preventive services? What mix of public and private institutional mechanisms would minimize administrative costs?

The more we know about the answers to questions like these, the better we can optimize an affordable UCC plan to deliver superior health care outcomes.