The 2021 expansion of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) was a watershed moment in U.S. social policy. In addition to increasing the size of the credit, the reform made the full amount available to America’s lowest-income families for the first time, lifting 3.7 million kids out of poverty while benefiting over 60 million children in total.

The reform also innovated by advancing payments every month. By delivering support on the same schedule as households incur expenses, from child care to mortgage payments, the expanded CTC provided families with a basis for financial stability. Unfortunately, when the Build Back Better negotiations faltered, the credit was allowed to expire at the end of 2021, reversing the gains made against child poverty and destabilizing family finances nationwide.

Legislative whiplash of this sort is the byproduct of Congress’ attempt to pass major social legislation along narrow party lines and under artificial spending constraints. As a rule of thumb, the more transformative the policy, the more its survival requires it to be permanently funded and passed by a durable majority. And the imperative to make policy gains durable is all the more compelling when the well-being of America’s children is at stake.

Therefore, the time has come to consider a bipartisan CTC expansion as not only the most viable path forward, but the ideal approach for creating the certainty and reliability families deserve. Yet some questions remain: Why act now? What would a bipartisan CTC expansion look like? Is bipartisanship viable? The reform options below address these questions.

Why now?

The CTC gives parents maximal choice and flexibility to raise the next generation. With complete flexibility on how the money can be used, parents make choices that benefit their families and our overall economy. In addition to supporting direct investments in goods like education and pediatric health care, research finds child benefits also support stronger and more stable families. By helping parents cover less obvious expenses, including routine bills, child benefits like the CTC alleviate household financial instability, which is a known risk factor for child abuse and neglect; depress consumption of temptation goods; and contribute to an overall healthier household.

These evergreen reasons for enhancing the CTC have become more compelling since the COVID-19 pandemic. Core public services were disrupted, large-scale unemployment persisted for months, community social activities were suspended, and many were left grieving loved ones. The CTC expansion in 2021 was well-timed to these disaster-like conditions, which put financial and psychological stress on families with young children in particular.

Families need this continued support as they tackle the long-term consequences of the crisis on child outcomes, which we have only begun to unpack. Early data on the learning loss induced by school closures suggest a widening gap in test scores between families with and without the means to supplement their child’s education, with learning declines concentrated among younger children and children in disadvantaged communities. Evidence suggests the 2021 CTC expansion helped parents supplement their child’s learning, and may have even contributed to the recent boom in school choice and home-schooling.

Researchers are also uncovering troubling findings on the effect of the pandemic on infants, though the full extent and long-term consequences of any adverse impacts remain unclear. Last year, a longitudinal study — not yet peer-reviewed — found a shocking decline in the measured IQs of babies born during the pandemic. Other research that has also yet to go through peer review indicates the pandemic elevated prenatal maternal distress that, in turn, was associated with changes in fetal brain development, suggesting “a potentially long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children.” Research published earlier this year found significant developmental delays in infants born during the pandemic and ruled out in utero exposure to SARS-CoV-2 infection as the cause.

Fortunately, abundant evidence documents the significant and positive effects of child benefits on outcomes related to health, educational attainment, and earnings in adulthood. A new cost-benefit analysis draws on this evidence base to argue an expanded CTC has a benefit-to-cost ratio as high as 10:1. The fallout from the pandemic simply makes a bipartisan CTC expansion unusually timely. This is all the more true given the evidence that children can largely recover from school and related disruptions if granted the chance. Pairing the urgency of the pandemic and the long-term payoff, the price of the program should not stand in the way of bipartisan support to extend the CTC expansion.

Principles for bipartisanship

Even if the policy case for the Child Tax Credit is a slam dunk, there is no guarantee that the politics will cooperate. Fortunately, there are strong signals that Republicans are open to expanding the CTC on a bipartisan basis — provided Democrats make it a priority.

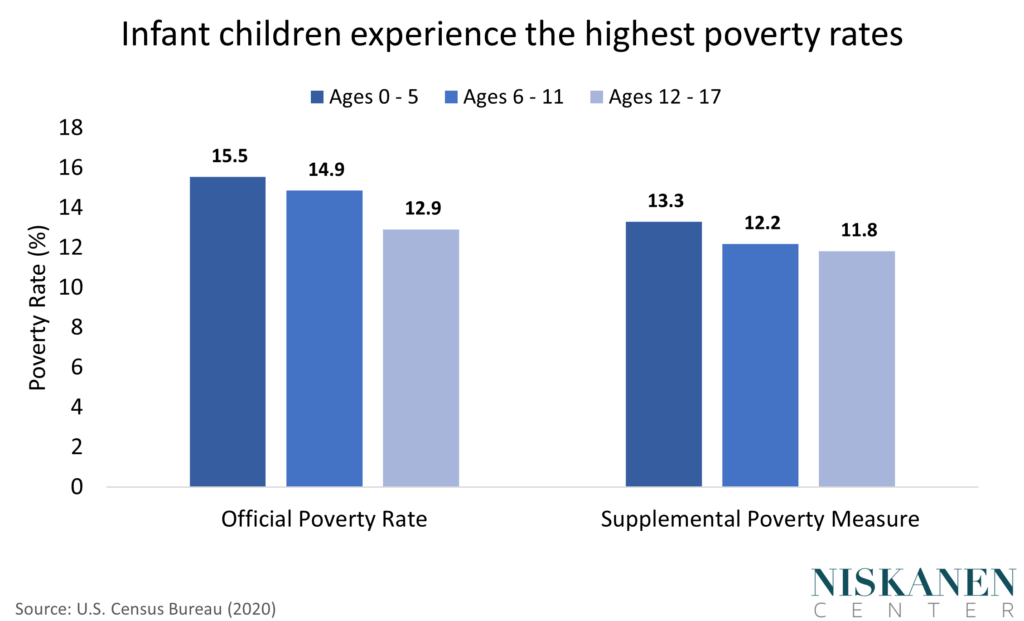

Securing robust bipartisan support starts by reconciling each sides’ core interests and concerns. For example, Democratic champions of the CTC favor full refundability because it packs the greatest anti-poverty punch, and because they wish to preserve the IRS’ investments in administering a monthly benefit. Republicans largely oppose full refundability out of concerns about their potential effect on work incentives — concerns that are lessened for parents of infants, for whom temporary leave from work may even be desirable.

Two high-level principles for a bipartisan CTC expansion immediately follow. A reform that would satisfy both sides of the aisle would:

- Strengthen the CTC’s work incentive for parents of school-aged children.

- Retain a larger, unconditional monthly benefit for young children or infant parents.

Together, these two design principles would alleviate Republican concerns about work incentives while allowing Democrats to preserve a monthly benefit for parents of young kids, the very households where a refundable CTC has the greatest per-dollar impact on child poverty.

Bipartisan CTC alternatives

The exact details of a bipartisan CTC expansion are ultimately up to Congress; however, we can use the above principles to outline a realistic set of reform options. For example, the CTC’s work incentive can be strengthened by increasing the credit’s size and phase-in rate.

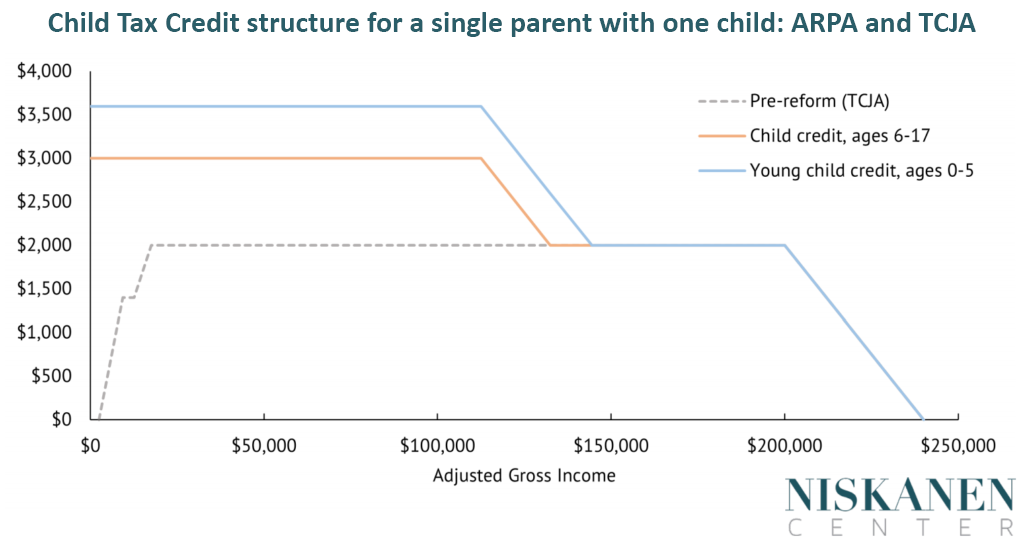

Under current law, the refundable portion of the CTC (known as the “additional CTC” or ACTC) phases in at a rate of 15 percent for earnings above $2,500, up to a maximum refund of $1,400. That is, for every dollar of earnings over $2,500, taxpayers get a 15-cent credit returned to them in a refund. The maximum credit of $2,000 per child under 17 phases in with a household’s income tax liability. High earners see the size of their credit start to shrink by five cents for every dollar they earn over $200,000 for single parents and $400,000 for married parents. These improvements were enacted as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and are scheduled to expire in 2025 absent further action.

The CTC’s minimum earning requirement and slow phase-in limit its value as a work incentive compared to related programs such as the Earned Income Tax Credit. To rectify this, our reform alternatives take inspiration from the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign, which proposed a $2,000 CTC for young children with a phase-in rate of 45 percent. As a recent Democratic precedent, we use a 45 percent phase-in rate in any scenario where a phase-in is included.

The 2021 CTC expansion, which Democrats passed as a component of President Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), increased the maximum CTC to $3,000 for children ages 6 to 17 and $3,600 for children below the age of six. The larger credit then phased down to the structure Republicans established in the TCJA at a rate of 5 percent for incomes above $112,500 for single parents and $150,000 for married couples. The 2021 reform further made the credit “fully refundable,” meaning households with low or no income could claim the full amount for every qualifying child.

While full refundability for the entire CTC is an unlikely starting point for a bipartisan compromise, our scenarios use the Biden CTC’s sizes and two-stage phase-out structure (first to TCJA levels, then down to zero for the highest earners) for simplicity and ease of comparison. Alternative structures that follow our two principles for bipartisanship are of course also possible. For example, Senator Romney’s (R-UT) Family Security Act proposes a maximum young child benefit of $4,200. Another proposal from Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL) and Mike Lee (R-UT) would increase the maximum CTC to $3,500 for children 18 and younger and to $4,500 for children younger than 6.

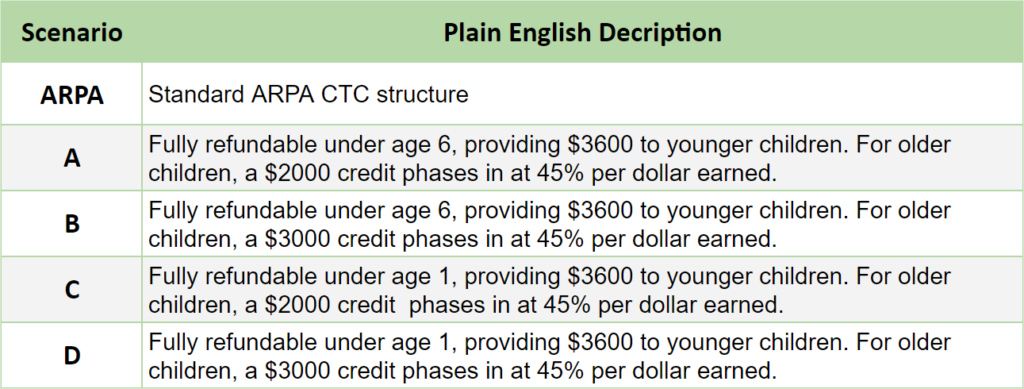

Lastly, our scenarios consider two alternative age cut-offs for the larger monthly benefit for young children: Below the age of six, and below the age of one. While we favor preserving full refundability for all kids below the age of six, a child benefit for newborns would be sufficient for preserving the IRS’ capacity to administer monthly payments and has the virtue of being minimally controversial.

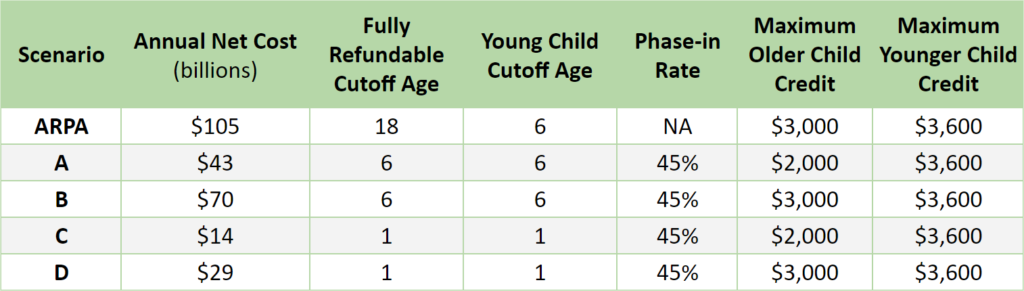

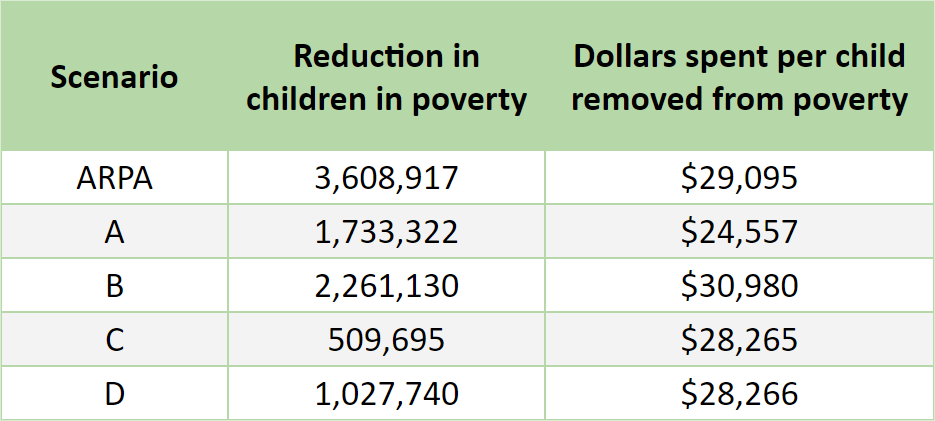

To illustrate the power of these parameters to advance powerful reforms, we have modeled four alternatives. These are summarized above alongside the ARPA CTC for comparison. The estimated net fiscal cost of a CTC expansion can vary widely depending on the scenario.

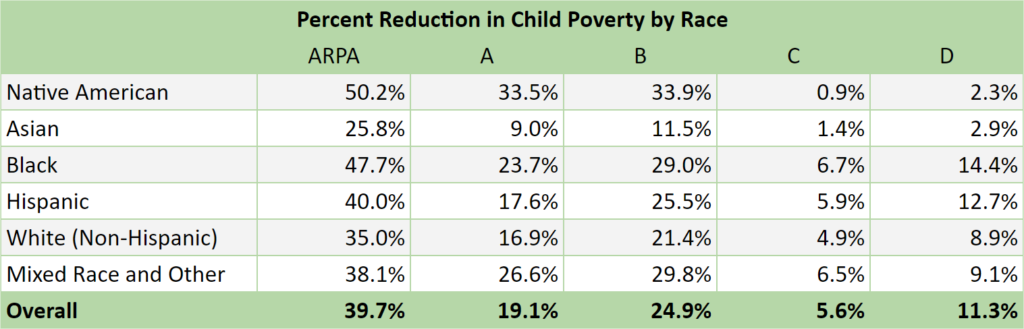

We next consider the impact of each alternative on child poverty. While it is hard to beat the ARPA CTC’s nearly 40 percent reduction in child poverty, our alternatives still produce substantial reductions in child poverty with greater efficiency per dollar spent. For example, Scenario A combines a $2,000 CTC with a 45 percent first dollar phase-in for kids ages 6-17 and a $3,600 fully refundable CTC for kids below the age of six. This would reduce child poverty by roughly 19 percent at the cost of roughly $24,000 in net expenditures per child lifted out of poverty.

Even our most conservative CTC reform option, Scenario C, still makes a significant dent in racial income disparities. At an annual cost of just $14 billion, this scenario would only preserve a $3,600 fully refundable CTC for children in their first year of life. Yet it would reduce the number of Black children in poverty by nearly seven percent.

A note on potential offsets

A bipartisan CTC expansion will require budgetary offsets, whether through tax increases or spending cuts. The annual costs of our reform scenarios range from $14 billion to $70 billion, providing negotiators with a wide range of options.

One potential revenue source merits special consideration: extending the repeal of the personal exemption. The TCJA’s individual tax provisions will expire at the end of 2025. A 10-year CTC expansion beginning in 2022 could therefore extend the elimination of the personal exemption in the same budget window. Projections from the Joint Economic Committee suggest that this would raise approximately $170 billion annually. This alone represents sufficient revenue to fund our most expensive reform option even after accounting for the 2025 expiration of the existing CTC, which will add to the net cost of an expansion in the years thereafter. Given that the 2017 expansion of the CTC was explicitly designed to compensate families for the end of the personal exemption, combining these two reforms only makes sense.

Conclusion

With the expanded Child Tax Credit expiration earlier this year, a bipartisan expansion has emerged as the best path forward for investing in America’s families and children. While Democrats and Republicans have different visions for reforming the CTC, we at Niskanen believe those differences can be reconciled in a way that both promotes work and locks in meaningful reductions in child poverty going forward.

Our analysis modeled four CTC reform options to show what a productive compromise might look like. In all four alternatives, we preserve a fully refundable monthly benefit for young children while strengthening the CTC’s work incentive for parents of older children. By varying the size of the maximum credit and the age cut-off for the young-child benefit, we show that policymakers have a wide range of options for controlling costs and optimizing the per-dollar poverty impact.

These reform options are meant to be illustrative, and are admittedly far from our ideal reform: the Family Security Act. Yet with politics being the art of the possible, our analysis has sought to demonstrate how a somewhat more modest approach puts a bipartisan compromise easily within reach.