The Inflation Reduction Act and its $369 billion investments in clean energy are cause for celebration. But our work is far from finished. Modelers estimate that implementing the IRA will put the U.S. on track to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030 compared to 2005 levels–still significantly short of the science-backed goal of 50 percent.

Meanwhile, some commentators have used the IRA’s victory to dismiss some policy tools that were not included in the law. In particular, some left-leaning climate activists see permitting reform as too risky and carbon pricing as too unpopular to be part of our policy arsenal. But just because we have finally picked up the screwdriver doesn’t mean we should throw away our hammer. Yes, the subsidies and incentives in the IRA will jump-start clean energy across the country, but we need to do more to complete the transition to a low-carbon economy.

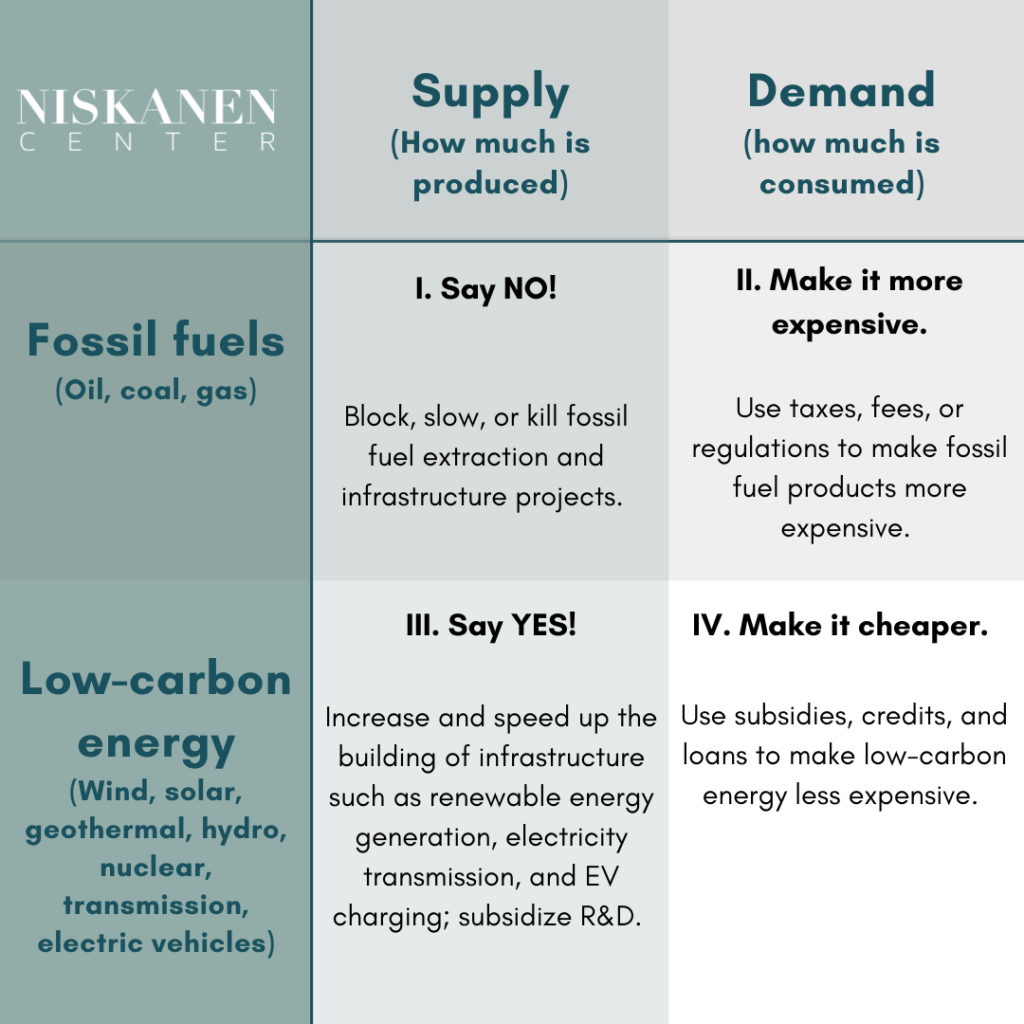

Climate policy: a dance in four quadrants

As anyone who’s taken Econ 101 knows, supply and demand are the basic elements of market economics. But to deal with the complexities of climate policy, we need to move beyond the models we remember from our college textbooks, where supply and demand curves intersect at the optimal price with no changes in technologies, resource scarcity, political constraints, or social attitudes. Instead, we should use a supply-and-demand matrix that allows for changes in all those things.

Each quadrant has its own set of policy tools. Some of these may be administrative. For example, a keep-it-in-the-ground approach that prohibits oil and gas drilling on federal lands would fit in Quadrant I. Pollution pricing, including both broad carbon taxes and more limited initiatives like the IRA’s methane tax, would fit in Quadrant II. Permitting reform for electric transmission and subsidies for research on green energy and materials would fit in Quadrant III. Tax credits for rooftop solar make it cheaper to generate renewable energy (Quadrant IV).

Some policies synergistically link quadrants. For example, building more electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure (Quadrant III) makes it easier to use EVs, encouraging demand (Quadrant IV). Bill Gates’ “green premium,” the cost differential between clean and dirty options, illustrates another linkage. The premium can be reduced either by making dirty options more expensive (Quadrant II) or by making green options less expensive (Quadrant IV) – or, best of all, doing both simultaneously.

Filling in the quadrants is also a matter of politics.. For example, Quadrant I is often easier to mobilize around. To decrease supply of fossil fuels (Quadrant I), advocates can tap into local protectionism and NIMBYism (Not In My Back Yard) to encourage people to say “no” to fossil fuel projects. It is easy to spur passionate action to protect communities from the threats to their air and water. Fossil fuel suppliers enjoy favorable treatment not available to low-carbon options, including categorical exemptions from the National Environmental Policy Act and streamlined federal permitting processes. Nonetheless, advocates have utilized the tools available to block, slow, and kill some extraction or pipeline projects: multi-veto-point permitting processes, Endangered Species Act challenges, limiting access to federal lands, and popular protests.

However, making fossil fuels more expensive (Quadrant II) is generally unpopular. The main policy tools in this quadrant are carbon pricing (via a tax, fee, or cap-and-trade program) or regulations that effectively make fossil fuels more expensive by constraining supply. Removing existing government supports, such as federal subsidies for coal clean-up costs, can also increase prices. As commentators have pointed out, carbon pricing can be a particular target of political opposition because it puts a transparent number on the cost of fossil fuels, even though it may l be cheaper than regulation and brings in revenue that can offset its regressive effects and fund sustainable energy.

If increasing the costs of fossil fuels can feel like a burden, then decreasing the costs of clean energy (Quadrant IV) can feel like a gift. Much of the IRA fits in this quadrant. It gives people tax credits that reduce the cost of purchasing rooftop solar, heat pumps, EVs and more. Indeed, opponents found it difficult to argue against the merits of making clean energy cheaper and easier to access. The sticking point is usually finding the money to pay for the subsidies and credits. In the IRA, the money comes from a corporate minimum tax. Future efforts to continue driving demand for clean energy could look to carbon taxes or fees to fund the good stuff while simultaneously driving down demand for more polluting options.

Some parts of the IRA, such as production tax credits to juice the supply of wind and solar, fall into Quadrant III. But other aspects of increasing the supply of low-carbon solutions are both urgently needed and politically difficult. To say “yes” to new infrastructure, local actors must adopt a YIMBY (Yes In My BackYard) attitude. State and federal governments must enact streamlined rules for siting and permitting that takes some power away from NIMBYs who would block clean energy projects. At a minimum, the federal government could offer the same treatment to wind, solar, and geothermal projects that it has offered to oil and gas for decades: streamlined permitting on federal lands, a clear and uncomplicated federal siting authority, and risk management assistance. A benefit of the clean energy supply quadrant is that the more we do, the easier it gets, as companies and workers learn how to build.

Sequencing the steps

Carbon-pricing critics have made the unremarkable point that driving up prices for fossil fuels is politically more difficult than subsidizing clean energy. No one needed the IRA to tell them that is true;ten years of federal production tax credits for wind and solar and no federal carbon tax are proof enough. But the implication that climate hawks should abandon carbon pricing and exclusively pursue subsidies is surprising — and wrong.

Critics of carbon pricing often say that pricing can’t do it all. Yet hardly anyone thinks that way, any more than anyone thinks that EV subsidies, blocking pipelines, or any other single measure can do the whole job by itself. If the supply of clean energy is constrained by other factors such as siting and permitting hurdles (Quadrant III) then we can price and block and subsidize all we want but will not be able to deploy enough clean energy to meet needs sustainably.

That said, carbon pricing critics may have a point about how to sequence all of the policies. Resistance to increasing fossil fuel costs is particularly stringent when people and businesses don’t see alternatives. Building up clean energy options and then increasing prices for dirty options makes sense from a practical and political standpoint, as clean-energy employers start competing with fossil-fuel employers in influencing elected representatives.

However, in the electricity sector, clean energy is already available and cheaper than coal in many cases. The problem is that much of that competitively-priced clean energy is now blocked by siting delays and by a lack of transmission capacity. Some clean energy is so cheap its cost is negative – producers have to pay people to use their clean energy. It’s hard to entice new developers to bring more renewables online when they can’t sell their electricity. To keep the transition going, we need to build more high-capacity transmission to connect clean energy to consumers. Transmission capacity has additional benefits, such as making the grid more resilient to climate-driven extreme weather events and possible power outages. That, again, is where permitting reform comes in.

At its heart, the energy transition comes down to how quickly we can make clean options the clear winners when competing against dirty ones. We are trying to turn a huge ship on a short timeline, and need all the propellers spinning. We need to decrease fossil fuel supply and demand for them, and at the same time, to increase the supply of clean energy and demand for it. We need an “all of the above” climate policy. Where an “all of the above” energy policy usually means utilizing all energy sources, renewable or fossil fuels, I am using “all of the above climate policy” to mean utilizing all the available policy tools.

The IRA is a seminal and critical start on federal climate policy. But it’s not an excuse to abandon our other tools; indeed, it is all the more reason to reach for them. As the subsidies and credits in the IRA drive demand for clean energy, now is the time to attack other barriers to ramp up supply of clean energy. That means taking our foot off the brakes on clean energy by removing the regulatory barriers blocking ready solutions and tapping the brakes on demand for fossil fuels by implementing a carbon tax. By pursuing an “all of the above” climate policy that pushes forward with low-carbon solutions while pulling back on fossil fuels, we can encourage a swift and orderly transition to a clean and stable economy.