This piece was originally published by The American Compass on November 23rd, 2020.

Pro-worker conservatives faced an important test last week and nearly failed. I’m of course referring to Judy Shelton’s nomination to the Federal Reserve board, which was narrowly blocked on a 50-47 vote.

Majority Leader Mitch McConnell retains the power to reintroduce her nomination, but with Senators Chuck Grassley and Rick Scott in quarantine, and the newly-elected Democratic Senator from Arizona, Mark Kelly, expected to assume office in early December, Shelton simply doesn’t have the votes to warrant a redo.

For many observers, it was a surprise that the vote was close at all. President Trump’s election in 2016 was supposed to have been a repudiation of Shelton’s anachronistic, “supply-side” ideology in favor of a conservative populism that put the interests of workers first. We now know this was a lot of hype, and that Trump was co-opted by such supply-side luminaries as Steve Moore, Art Laffer and Larry Kudlow right out the gate. And yet Shelton’s record is so overtly contradictory with everything Trump stands for that one can feel justified in their surprise nonetheless. To wit:

- Where Trump says he favors looser monetary policy, Shelton advocates a return to a “hard money” gold standard.

- Where Trump argues “a country without borders is not a country at all,” Shelton believes “North America Doesn’t Need Borders,” and that we should work towards a North American Union with a common currency called the Amero.

- Where Trump wants a weaker dollar to promote U.S. exports, Shelton is a staunch opponent of currency depreciation, and wrote in 2011 to “beware” the Obama administration for favoring precisely that.

- Where Trump favors using tariffs to protect American industry, Shelton says talk of protectionism makes her “embarrassed to be an American.”

- And where Trump favors a tight labor market, achieved in part through immigration restrictions, Shelton praised “the inflow of foreign labor [from Mexico]” as a boon to the U.S. because it “diffuses wage pressures.”

In other words, merely calling Judy Shelton a supply-sider puts it too mildly. Fetishizing tax cuts is one thing. Shelton, in contrast, is a living caricature of the ’90s-era, “New World Order”-style globalists that haunt Alex Jones’s fever dreams.

The Impossible Trinity

So why was the vote so close, with Mitt Romney and Susan Collins as the only Republicans voting to oppose? For the most part, Senate Republicans were simply eager to give Trump a final win, and didn’t care whether it advanced the goals of Trumpism, per se. Others, like Senators Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio, seemed to think her views were actually consistent with pro-worker conservatism after all, if only in an inscrutable, 5D-chess sort of way.

This latter interpretation is by far the most contrived, but for that reason it’s also the most interesting. Shelton’s populist proponents point to her writings in favor of a Bretton Woods-style international monetary system, which — the theory goes — would reduce the financialization of the economy and help correct global trade imbalances to the benefit of the American working class. In contrast, as Shelton writes,

The current monetary regime permits governments to knowingly distort exchange rates under the guise of national monetary autonomy while paying lip service to avoiding trade protectionism. It empowers central banks to channel the benefits of monetary policy decisions to some people at the expense of others, pitting wealthy investors against average savers. It facilitates cheap government borrowing. The shift toward increasing government influence over economic outcomes is anathema to the free market doctrines propounded by [Milton] Friedman.

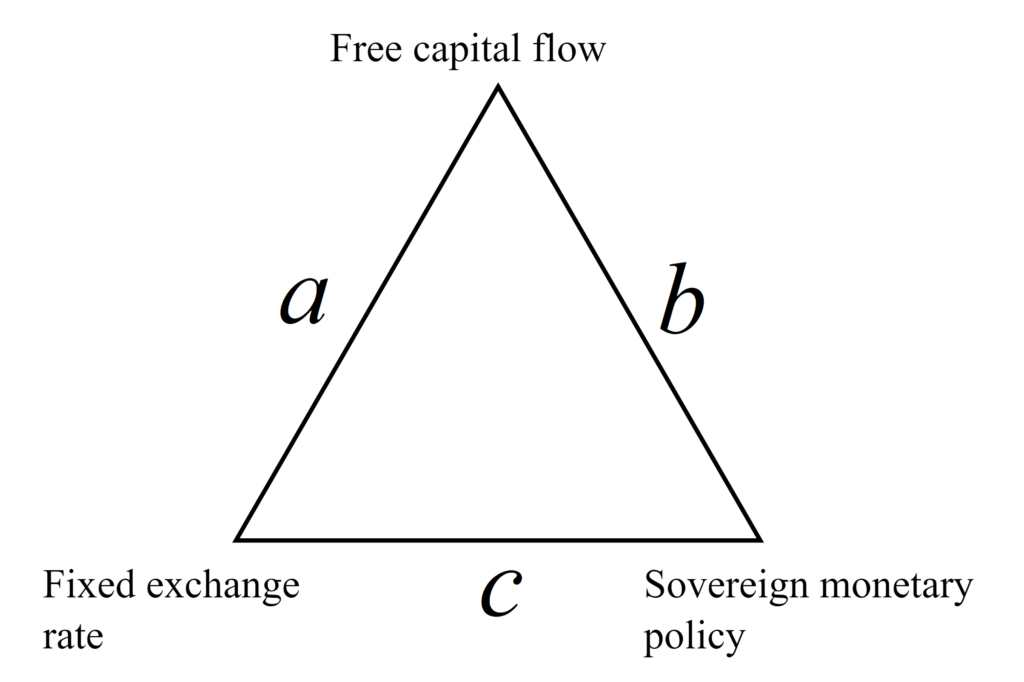

Unpacking this requires a bit of background. According to the “impossible trinity” or “trilemma” of international economics, a country can never have a fixed foreign exchange rate, free movement of capital, and an independent monetary policy all at the same time. While seemingly distinct policy levers, they are in fact deeply interdependent — so much so that a country is always forced to pick two and only two of the three.

Pick two, any two.

The contemporary United States has an independent monetary policy and an open capital account. In turn, the U.S. dollar is free floating. To see why, suppose one day the Federal Reserve decided to maintain a fixed exchange rate against the Euro. If the Fed and the ECB both continued to maintain independent monetary policies, the certainty of a fixed exchange rate would cause investors to move their capital into whichever country had higher rates of return, i.e. interest rates, which these days is the U.S. The inflow of foreign investment would then boost demand for the U.S. dollar, causing its value to increase relative to the Euro. In order to maintain the fixed exchange rate, the Fed would either have to loosen its monetary policy or restrict the investment inflow directly through capital controls. The only other option would be to counteract or “sterilize” the upward pressure on exchange rates by buying a proportional reserve of Euros, but since this doesn’t eliminate the underlying arbitrage opportunity it’d be a short-run strategy at best. Soon enough, maintaining a fixed USD-Euro exchange rate would force the U.S. to either adopt capital controls vis a vis Europe or abandon our monetary independence altogether. Most likely, though, the entire arrangement would simply fall apart.

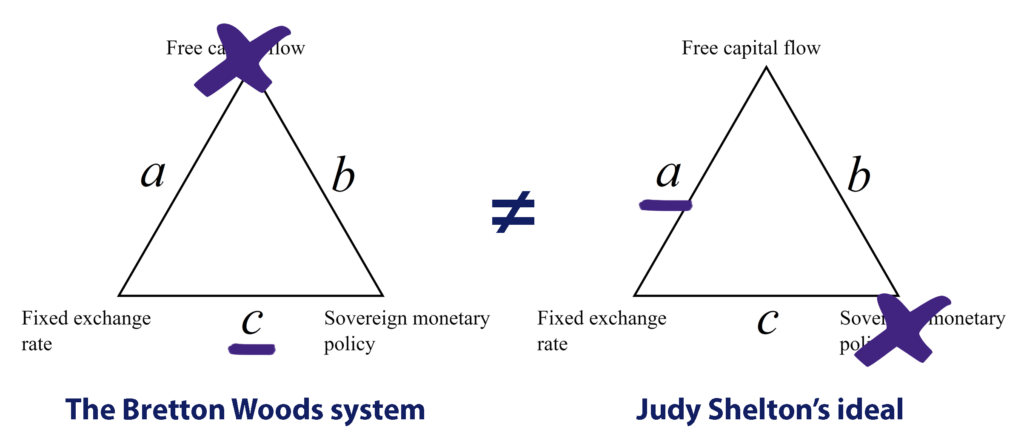

While the above example is purely hypothetical, the post-war Bretton Woods system ultimately unraveled through a similar process. Under the short lived arrangement, the rest of the world pegged their currencies to the U.S. dollar, which in turn was convertible to gold at a fixed price, making the gold-backed U.S. dollar a kind of de facto global currency. Maintaining this equilibrium required a lot of transnational coordination, facilitated by each country’s central bank in concert with the World Bank and IMF. But by the early 1970s, the fundamental value of the U.S. dollar was facing enormous downward pressure given high deficits and inflation at home, and fast catch-up growth in countries like Germany and Japan abroad. To maintain the dollar’s convertibility with gold, the Fed was thus forced to sell off its gold reserves until defending the peg became untenable.

The Bretton Woods era came to a close when Nixon abandoned the dollar’s convertibility to gold in 1971. Ever since, advanced countries have resolved the impossible trinity by opting for an independent monetary policy and open capital account in exchange for floating exchange rates. In theory, this means balance of payment issues should resolve themselves through the equilibrating forces of the international market, rather than requiring continuous, top-down management from a quasi-global government. This is what makes the post-Bretton Woods equilibrium so resilient: Where Bretton Woods was fragile to mere acts of omission, undermining its successor requires overt acts of commission, whether in the form of active currency manipulation or the imposition of capital controls.

Shelton Wars as Class Wars

China is of course guilty of both. Since the mid-1990s, China has maintained a de facto peg between the U.S. dollar and the Chinese Yuan. Exchange rate stability and the Yuan’s relative cheapness were key to China’s rapid industrialization and export boom in the early 2000s, which manifested in the U.S. as rapid deindustrialization and a skyrocketing trade deficit. After 2005, the Yuan was allowed to appreciate against the dollar, ending China’s explicitly mercantilist phase. Nonetheless, since 2009 China has unofficially targeted the Yuan’s value vis a vis the dollar and other major currencies within a particular range.

So would Shelton’s proposal for a new Bretton Woods solve this problem? It might sound like it at first blush. After all, had China been forced to adopt a common, gold-backed currency as a pre-condition for normalizing trade relations with the U.S. and Europe, they wouldn’t have been able to strategically devalue. American manufacturing jobs would have been saved, and our trade deficit averted!

Or not… Remember, China’s currency is no longer undervalued, and yet China continues to exploit the Yuan’s stability through domestic policies that suppress worker wages relative to labor productivity — what can be thought of as a kind of “internal” devaluation. The strategy has two main purposes. First, it increases China’s international competitiveness by making Chinese labor appear “cheap” relative to real output per worker. And second, it transforms wage income that the household sector would’ve consumed into an enormous pool of savings for the corporate sector to invest. China’s extraordinary savings rate — 45% of GDP — manifests as a large current account surplus, which must be balanced by China’s trading partners through equally large current account deficits.

Between various forms of financial repression, a weak social safety-net, a reserve army of rural labor, and high rates of income inequality, the Chinese model works by systematically transferring wealth from workers to the capitalist class. China’s investment-driven growth model is thus financed through a kind of internal class war, as Matt Klein and Michael Pettis have put it, creating enormous global payment imbalances as a byproduct. In other words, Chinese currency manipulation, and currency wars more broadly, are simply not the main source of global trade imbalances, at least not today.

A Gold-convertible Straitjacket

Consider that Germany employed a similar strategy as China in the context of the Eurozone — a multinational monetary system committed to extremely stable price inflation, exactly as Shelton favors. Indeed, as a common currency, the Eurozone is equivalent to each member country maintaining a fixed exchange rate between each other’s currency. Given the impossible trinity, this means member countries are forced to abandon their monetary policy independence in favor of a single policy controlled by the ECB. Investors thus have total certainty that a Euro invested in Germany will maintain its value against a Euro invested in Greece, and vice versa.

Germany was nevertheless able to exploit the Eurozone’s de facto currency peg through a series of reforms in the early 2000s designed to reduce unit labor costs, i.e. to restrain wage growth relative to output per worker. This made German labor artificially “cheap,” helping draw in demand from other Eurozone countries while simultaneously transferring income from German households to German banks and corporations for reinvestment. The result was a manufacturing renaissance, combined with one of the largest current account surpluses in the world. Sounds great, right?

Wrong. In the Eurozone periphery, less competitive countries like Portugal, Spain and Greece were forced to balance Germany’s excess savings through mass unemployment and spiraling indebtedness. Pre-Eurozone, the capital that fled Greece for Germany (say) would have been automatically offset by a cheaper Greek drachma, and with an independent monetary policy the sovereign debt crises that ensued would’ve been easily avoided. Yet with the relative “price” of a German Euro and Greek Euro fixed, any bilateral imbalance between the two countries had to instead be resolved on the “quantity” side through direct fiscal transfers, otherwise known as bailouts. In exchange, the European Commission, ECB and IMF demanded far reaching structural reforms — privatization of state owned assets, labor market deregulation, and cuts to public services — in order to mimic Germany’s “internal” devaluation and thus impose a similar degree of “competitiveness.” That is, rather than make Germany end its beggar-thy-neighbor class warfare, the beggared neighbors were made to stoop to Germany’s level.

A cynic would say this was the plan all along. Like Judy Shelton herself, the Eurozone is a product of the neoliberal ethos that permeated the late 1990s. With the Soviets defeated and trade barriers falling worldwide, the last mile of economic integration would be achieved through regional trading blocs; common markets with free movement of labor, harmonized regulations and, yes, a common currency. In a clever bit of political economy, a common currency would both minimize foreign exchange risk — a boon for multinational corporations with outsourced supply chains — while forcing national governments into Tom Friedman’s famed “golden straitjacket.” Without monetary independence, countries would be forced to maintain balanced budgets. And without a transnational fiscal authority, differences in national competitiveness would have to be adjusted for through wage repression and austerity.

As Shelton put it in her 1999 testimony to the House Financial Services Committee,

The world economy today is rapidly becoming a global common market. As we have seen in Europe, the sequence of development is (1) you build a common market, and (2) you establish a common currency. Indeed, until you have a common currency, you don’t truly have an efficient common market.

Bretton Woods, true and false

In this light, Shelton’s older writings in favor of a North American Union and her more recent writings in support of a global common currency are intimately related. Only by tying the nations of the world to a gold-convertible mast will capital be free to flow unabated, smashing labor unions, welfare states, and national industrial strategies along the way. Sure, global trade imbalances will persist if not worsen, and yes, peripheral economies will be pushed into lost decades, requiring endless bailouts from American taxpayers until the world economy is eventually subsumed into a fiscally-integrated global government, but so be it. At least there won’t be any more forex risk!

In reality, Shelton’s understanding of what made the Bretton Woods era so prosperous is fundamentally backwards. It was not the semi-fixed exchange rates, nor even the multinational monetary institutions, that made the system a success. On the contrary: As Dani Rodrik notes, of the three policies in the impossible trinity — fixed foreign exchange rates, an independent monetary policy, and free capital movement — central to the Bretton Woods system “were the controls it put on international capital mobility.” Under the principle of “embedded liberalism,” the architectures of Bretton Woods believed free trading, liberal democracies should be empowered to use the very same capital controls needed to maintain fixed exchange rates to, if desired, pursue expansionary fiscal policies, build large welfare states, and cultivate domestic industries. And so they did, building robust middle-classes along the way.

The mystery of why populist conservatives like Senator Josh Hawley and Marco Rubio voted to confirm Shelton is therefore solved. In short, they took her at her word that she wants to restore the conditions for a robust middle-class, conditions we rightly associate with the Bretton Woods era. The only problem is that Shelton’s vision has little to do with the actually-existing Bretton Woods system — a system premised on maximizing sovereignty over the domestic economy. Instead, Shelton namedrops Bretton Woods while actually describing the disembedded liberalism of the EU and Eurozone — hyperglobalist institutions designed to hogtie democracy in the name of squashing residual market inefficiencies. In other words, far from defending a Trumpian view of national sovereignty, for Shelton national sovereignty is the problem she’s spent her 35 year career trying to solve.