This post was originally published by Econofact on May 27, 2020.

The Issue:

The coronavirus crisis has shone a spotlight on existing disparities in access to health care in the United States and on the implications that this uneven access can have in the context of an infectious disease pandemic. Immigrants, especially non-citizens, are less likely to be insured than natives. Moreover, non-citizens are less likely to have a usual place for health care and to cite cost being a barrier to health care. The gap in insurance is driven by differences in access to both public and private health insurance. This gap can lead to worse health among non-citizens, but also, can have negative public health consequences for the general population, particularly in the setting of communicable diseases, such as COVID-19.

Immigrants are less likely to have health insurance than natives. Lack of access to medical care can adversely impact public health in a pandemic.

The Facts:

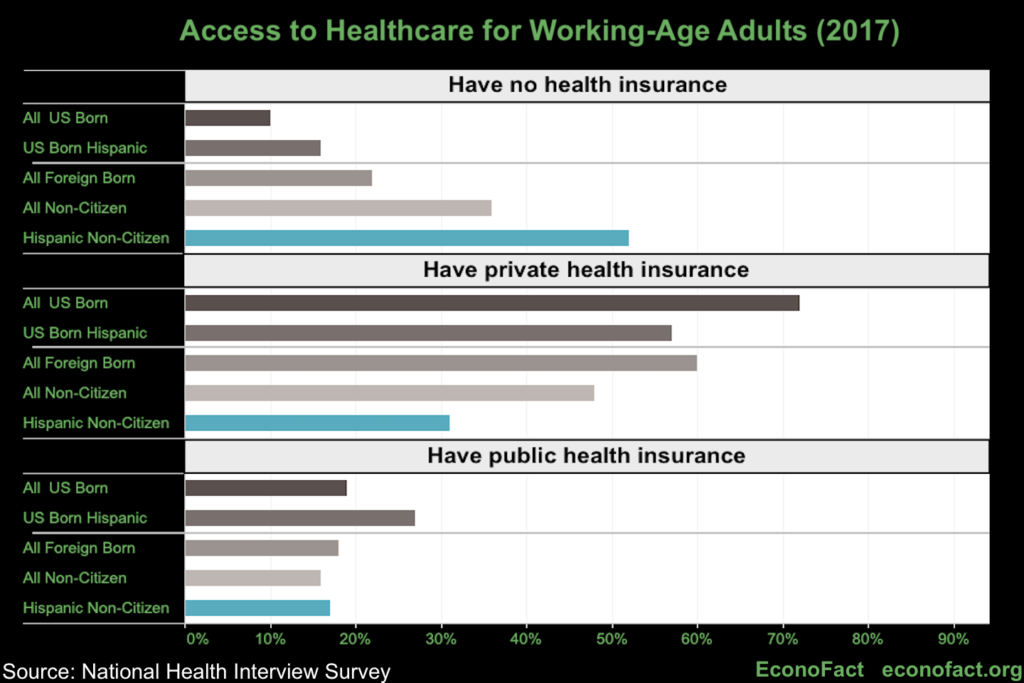

In 2017, the majority of the U.S. working-age population received coverage through private health insurance (almost 70 percent). An additional roughly 19 percent were covered by Medicaid or other public programs, and 12 percent remained uninsured. However, there are large disparities in access to health insurance between immigrants (foreign-born) and natives (U.S.-born).

Immigrants, especially those who have not acquired citizenship through naturalization, are less likely to have private health care coverage than those who are native-born. Working-age adult non-citizens are 24 percentage points less likely to have private health insurance than U.S.-born adults (85 percent of all non-citizens are working-age adults.) This gap is slightly wider when comparing Hispanic non-citizens to Hispanic U.S.-born adults (26 percentage points, see chart above). Much of this gap is explained by differences in the availability of employer-provided health insurance. Non-citizens are more likely to work at smaller, non-public firms, which are less likely to provide insurance. Additionally, non-citizens have shorter job tenure and earn lower wages, which limits their access to employer-provided insurance (see hereand here).

Due to limitations on eligibility, Public Health Insurance does not fill in this gap in private insurance coverage; non-citizen adults are 26 percentage points more likely to be uninsured than the U.S.-born adults. The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 introduced new limits on access to Public Health Insurance programs for lawfully present non-citizens. At the federal level, newly-arrived adult permanent residents were made ineligible for Medicaid for their first five years of residence in the U.S. While states could use their own funds to restore eligibility during this period, only eight states did so. Comparing within disadvantaged individuals, who are more likely to meet income eligibility criteria for Public Health Insurance, U.S.-born Hispanics with at most a high school degree are twice as likely to receive Public Health Insurance than non-citizen Hispanics with at most a high school degree (40 percent compared to 19 percent).