This piece was originally published via EconoFact on January 27, 2020.

The Issue:

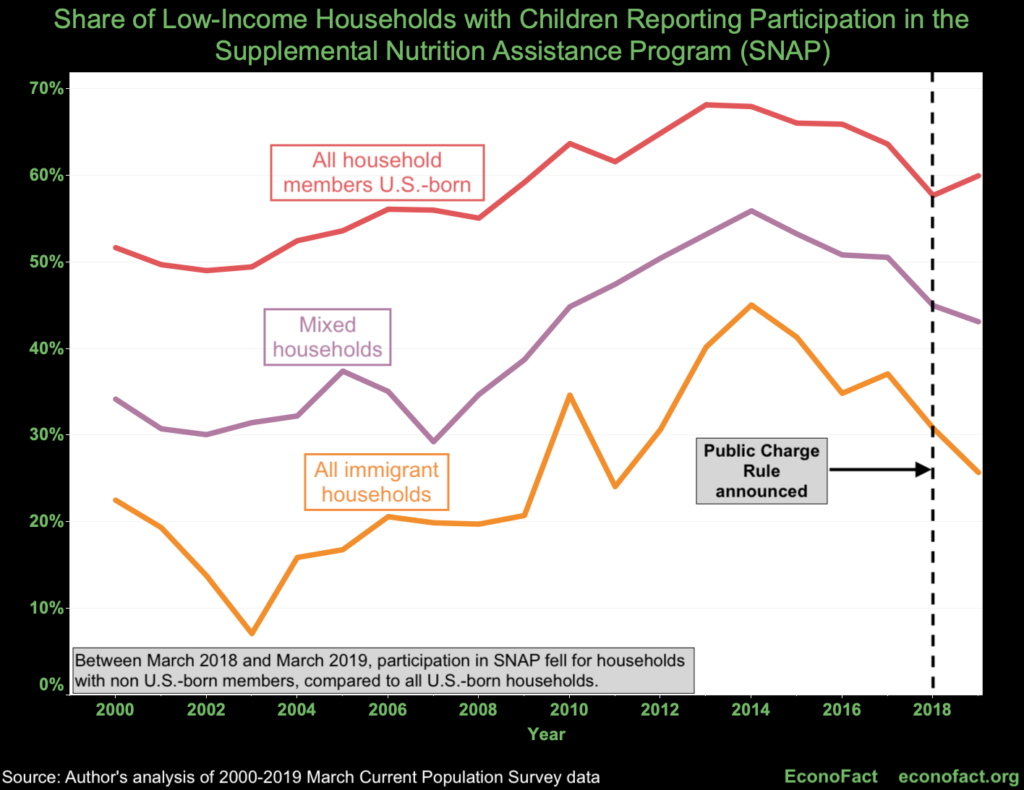

Policy-makers worry about the financial burden of immigrants on the taxpayer funded safety net. The Trump administration’s August 2019 “public charge” guidance aims to discourage non-citizen participation in federal safety net programs and to deny admission to the country to those deemed likely to become a burden on the state. Legal challenges are underway, but on January 27th, 2020, the Supreme Court ruled that the policy could go into effect in the meantime. In light of this, the administration will factor in the use of non-cash safety net programs (notably Medicaid and SNAP) in determining admission to the United States and changes of status. Would this policy change significantly impact future spending on safety net programs?

Even though immigrants represent a small share of SNAP and Medicaid beneficiaries, “chilling effects” from the public charge rule could lead to noticeable reductions in program participation and costs.

The Facts:

Public charge is not new, but under the rule it will take on new significance in immigration decisions. Public concern that newcomers might represent a financial burden to the state has been evident since colonial times. When Congress passed the first general immigration law in the 1880s, it included the ability to deny admission or deport individuals who were “unable to take care of himself or herself without becoming a public charge.” However, the law did not specify what “public charge” meant and interpretations have varied over the years. Previous guidance from 1999 had specified that the use of cash benefits or long-term care support could be considered in immigration decisions. On August 14, 2019, the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) published new rules expanding the definition of public charge to include prior use of food and medical assistance, and to emphasize a prospective determination about a migrant’s likely future self-sufficiency (see for instance here and here).

The consideration of whether someone is likely to become a public charge plays a role for people applying for admission from outside of the country, and for those already in the U.S. seeking to change status—those seeking to acquire permanent residence (green cards) in particular. Some types of immigrants, such as refugees, are excluded from the rule. In addition, the rule should not directly affect those who already have green cards: The new public charge rule does not affect the transition to citizenship, so legal permanent residents are not penalized for using safety net programs in most circumstances. (They could be denied re-admission if they leave the country for 180 days, however, because the rules applying to “admissibility” would be triggered.)