Last Friday, Judge Reed O’Connor of the Federal District Court in Fort Worth issued a summary judgement in a lawsuit known as Texas v. United States. Appeals are expected, but if the ruling stands, it could strike down the ACA in its entirety and end healthcare coverage of millions of Americans who get insurance through the ACA exchanges or Medicare expansion.

Texas v. U.S. lays bare the flaws of the ACA. Yes, the ACA has made healthcare accessible and affordable for many who would otherwise fall through the cracks, but it is a legislative, administrative, and economic kludge. From the beginning, it has been at risk of collapsing from its own complexity. The new ruling shows more dramatically than ever why we need real healthcare reform.

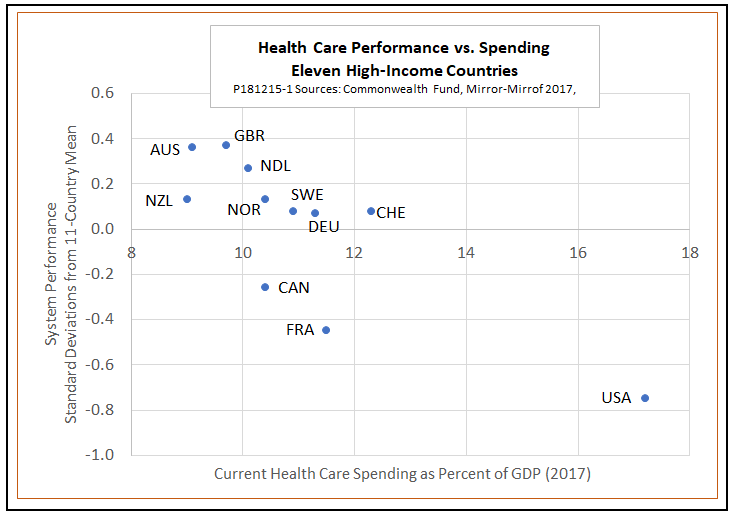

A healthcare system to be ashamed of

The U.S. healthcare system is a national disgrace. Americans pay more for healthcare than our peers in other high-income countries but have far less to show for it. I’ve used this chart many times before, but here it is again, in case you missed it:

The problem isn’t that American hospitals and doctors don’t do good work. In fact, the Commonwealth Fund study on which the chart is based gives the United States high scores in that regard. For example, Americans who are hospitalized for heart attacks or strokes, or who are treated for breast or colon cancer, have survival rates well above the eleven-country average. U.S. doctors are rated better than average in discussing treatment options and following patient preferences. Preventive care also receives high marks.

Unfortunately, those strong points are more than offset by low marks for access and affordability. More American patients report cost-related access problems than do people in other countries and more say they have problems paying medical bills. There are wider differences in access and health outcomes between low- and high-income patients in the United States than elsewhere. The high administrative costs of the fragmented U.S. healthcare system are a further drag on performance.

Insuring the uninsurable

The central problem facing would-be reformers is that we rely too heavily on private and employer-sponsored insurance at a time when healthcare has increasingly become an uninsurable risk. For the uninsured and uninsurable, an illness or accident can mean financial ruin. That is not only true of low-income families, for whom even routine healthcare needs can be financially challenging. Healthcare costs are so unevenly distributed across the population that even middle- and upper-income families can’t afford the costs of major illnesses and chronic diseases. Just 5 percent of the population account for half of all spending, while the top 1 percent account for more than a fifth.

For many households near the top of the spending curve – those with pre-existing conditions — conventional health insurance is not an option. Their medical needs fail to meet two traditional standards of insurability.

One is that an insurable risk must be the result of unpredictable chance. In reality, though, many individuals suffer from chronic conditions like diabetes that make them certain to require costly care for the rest of their lives. Others have genetic markers that make them medical time bombs from the point of view of private insurers. A study by the Kaiser Family Foundation estimated that 27 percent of nonelderly have a pre-existing condition severe enough for insurers to deny coverage under pre-ACA standards. Some 53 percent of Americans report that they, or someone else in their household, has a pre-existing condition.

A second standard of insurability is that the actuarially fair premium — one high enough to cover the expected value of claims — must be affordable. However, an actuarially fair premium for many people with costly chronic conditions would exceed their entire income.

The Affordable Care Act applies several partial solutions to the problem of uninsurability. It mandates guaranteed renewal, which means that insurers can’t cancel policies for people who become ill. The ACA also provides for guaranteed issue, which means insurers must accept any applicants, regardless of pre-existing health conditions. A third mechanism, community rating, requires insurers to charge the same premium, based on average claims, to everyone in a general category regardless of their health status.

However, these features make the ACA vulnerable to adverse selection – the temptation for healthy people to remain uninsured and buy into the system only when they become ill. To minimize that problem, the original ACA included the individual mandate, under which people either had to buy insurance or pay a fine. That turned out to be the single most widely disliked feature of the law. In response, Congress reduced the penalty to zero earlier this year, an action that undermined a key pillar on which the ACA was rested. Whatever the legal and constitutional merits of Texas v. U.S., Judge O’Connor had economic logic on his side when he ruled that lifting the individual mandate invalidated the entire ACA.

What to do now?

In the wake of Texas v. U.S., the first need is somehow to keep the ACA limping along until a real fix can be put in place. Hopefully, the necessary legal or legislative measures will be taken quickly. Beyond that, we need real, lasting reform.

One of the most talked-about proposals is Sen. Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All. If enacted, that plan would move the United States to the top of the world performance chart in a single bound by providing universal first-dollar coverage for a wide range of healthcare services. That would outdo even countries like the U.K., Australia, and the Netherlands, where the government covers 70 to 80 percent of healthcare costs. However, the implications of the Sanders plan for the federal budget and taxes cause many observers to doubt its political feasibility.

In my opinion, reformers should instead look for some way to ensure universal, affordable access to healthcare while maintaining the principle that people who can afford to do so should pay a fair share of their own costs. In many previous posts, I have argued that the best way to do that would be a system of universal catastrophic coverage (UCC). Under UCC, the poorest families would get full coverage without deductibles, middle-class families would face out-of-pocket costs similar to those they pay under the ACA, and high-income families would be responsible for all but truly catastrophic medical expenses.

UCC has the potential for support across the political spectrum, a crucial consideration with a divided Congress on deck for January.

If you are a liberal, think of UCC as a scaled-down version of Medicare for All – one that guarantees universal affordable coverage while substituting high deductibles for new taxes as a way of getting the rich to pay their fair share. For my full pitch on UCC for liberals, read “Suppose Democrats Win on Medicare for All. What Then?”

If you are a conservative, think of UCC as a smarter way for the government to put the money to work that it now spends on Medicaid, Medicare, the ACA, tax deductibility of employer plans, and the rest of its messy jumble of programs. UCC offers all the scope any Republican could want for market-based incentives, transparency, and competition, without sacrificing the politically vital goals of universal accessibility and protection for pre-existing conditions. For details, read my post on Vox, “What a Good Conservative Health Care Plan Would Look Like.”

And, what if you are neither a liberal nor a conservative healthcare zealot? What if you just have the vague idea that all is not well, that we should do something, maybe, sometime, eventually at the latest?

If you are in that category, Judge O’Connor’s ruling should be a wake-up call. The time to get moving on healthcare is now.