The illness of universities is hastening the death of expertise.

To understand this illness, we have to go beyond Tom Nichols’s accusations against the college culture in The Death of Expertise, which I discussed in Part I. A good place to start would be the well-publicized opposition to free speech on college campuses, such as the debacle at Evergreen State. As this case suggests, the rejection or restriction of free speech when it clashes with prevailing campus orthodoxies is not just a trend at elite liberal-arts colleges, but runs the gamut from state universities with 97 percent acceptance rates to world-class research universities. Historically black colleges are affected, too: The most recent irony is James Comey having to shout over chanting protesters during his entire convocation speech at Howard University—in which he contended that we should stop criticizing universities for “not being the real world.” His final sentence was, “I look forward to an adult conversation about what is right and what is true.” That is one of the last things that is likely to happen on an American campus in the near future. But Comey had it right that the divide is about facts (“what is true”) as well as principles (“what is right”).

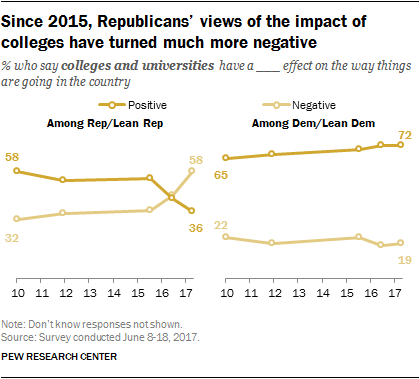

Given the recent episodes, which were preceded by years of conservative commencement speakers being disinvited after student protests, it is little wonder that conservatives have lost faith in academic expertise, as revealed in a Pew survey fielded in June 2017. The statement that “colleges and universities have a positive effect on the way things are going in the country” gained endorsements from 72 percent of Democrats but only 36 percent of Republicans. A majority of Republicans now have a negative view of the influence of higher education on American life, a dramatic reversal of opinion over just the last two years.

Source: Pew Research Center, “Republicans Skeptical of Colleges’ Impact on U.S., But Most See Benefits for Workforce Preparation,” July 20, 2017.

The Partisan and Ideological Split over Academics’ Knowledge Claims

Other survey research provides insight into the reason for this outburst of distrust. The evidence suggests that conservatives blame what they hear about universities on their faculties, which they perceive as disproportionately liberal.

Consider a question that was asked in two different nationally representative surveys, conducted a year apart. [1] The wording is slightly different in each survey, providing more robust evidence:

2013: “When you hear of new research findings from a prominent university such as Berkeley or Princeton about topics like global warming, racism, or the national debt, how believable do you think they are?”

They are almost certainly correct.

They are probably correct.

They are probably wrong.

They are almost certainly wrong.

2014: “Professors at American universities often present new evidence relating to important national topics like global warming or the prevalence of racism. When you hear of university research of this nature, how believable do you think it is?”

It is almost certainly correct.

It is probably correct.

It is probably wrong.

It is almost certainly wrong.

In 2013, only 11 percent of the sample thought that university research findings on politically relevant facts are almost certainly correct. Another 62 percent believed them to be probably correct. But 21 percent saw such research as probably wrong and 6 percent as almost certainly wrong. In 2014, the percentage seeing university knowledge as probably or almost certainly wrong rose slightly, to 21 percent and 9 percent. Nearly as many people saw university pronouncements as almost certainly wrong (6 percent in 2013, 9 percent in 2014) as those who saw them as almost certainly correct (11 percent and 13 percent).

The more striking story, however, is told in Table 1 below. The difference between self-identified Democrats and Republicans is remarkable. While only 8-10 percent of Democrats are distrustful of university knowledge, a full 55-59 percent of Republicans see university assertions as likely to be wrong. The same patterns holds for self-identified liberals and conservatives (only 4-7 percent of liberals see university knowledge as likely to be wrong, while 49-55 percent of conservatives do). Distrust of universities is essentially a conservative and Republican phenomenon.

Table 1. Trust in University Knowledge

2013

| All Respondents | Democrats | Republicans | ||

| University Knowledge “Probably” or “Almost Certainly” Correct |

73 percent | 92 percent | 45 percent | |

| University Knowledge “Probably” or “Almost Certainly” Wrong |

27 percent | 8 percent | 55 percent |

2014

| All Respondents | Democrats | Republicans | ||

| University Knowledge “Probably” or “Almost Certainly” Correct |

70 percent | 90 percent | 41 percent | |

| University Knowledge “Probably” or “Almost Certainly” Wrong |

30 percent | 10 percent | 59 percent |

Sources: See note 1.

The Partisan Split over Perceptions of Professors

Another question asked respondents about their perceptions of the partisan or ideological makeup of university faculty:

2013: “If you had to guess, what percentage of university faculty would you say lean toward the Democratic rather than Republican Party?”

2014: “Consider your impressions of the political ideology of American college professors, whether they tend to be conservatives or liberals. If you had to guess, what percentage of college professors would you say are liberals, are conservatives, or are something else? Your answer should total to 100 percent.”

The results displayed in Table 2 again show a remarkable partisan split. Americans as a whole see Democratic faculty outnumbering Republican faculty by 1.9 to 1 (65 percent to 35 percent), and liberal faculty outnumbering conservatives by 2 to 1 (57 percent to 29 percent). Democrats see a smaller advantage for the left (59 percent Democratic to 41 percent Republican and 50 percent liberal to 35 percent conservative, or a ratio of 1.4:1 in both cases). Republicans, on the other hand, perceive faculty to be about 75 percent Democratic to 25 percent Republican (3:1) and 70 percent liberal to only 21 percent conservative (3.3:1).

Table 2. Perceptions of Faculty Partisan and Ideological Makeup

2013

| All Respondents | Democrats | Republicans | |

| Perceived Percentage of Faculty Who Are Democrats | 65 percent | 59 percent | 75 percent |

| Perceived Ratio of Democratic to Republican Faculty | 1.9 to 1 | 1.4 to 1 | 3.0 to 1 |

2014

| All Respondents | Democrats | Republicans | |

| Perceived Percentage of Faculty Who Are Liberal | 57 percent | 50 percent | 70 percent |

| Perceived Ratio of Liberal to Conservative Faculty | 2.0 to 1 | 1.4 to 1 | 3.3 to 1 |

Source: See note 1.

We can compare these public perceptions to the best available evidence from scholarly studies of university faculty. Three recent studies—grounded in national surveys of university faculty conducted in 1996, 1999, and 2011—provide estimates of the ratio of liberal to conservative professors as 4.8:1, 4.8:1, and 3.2:1. If we average the results of these three studies, this suggests a ratio of around 4.1:1. [2] Apparently, then, both Democrats and Republicans significantly underestimate the degree to which liberal faculty members predominate. (Notably, these ratios cover entire university faculties, not just liberal arts and social science faculties, where the ratios are much higher.)

Is there a connection between distrust of the university and perceptions of its ideological balance? In a statistical analysis of the 2013 survey data, the 8 percent of the sample that perceived the ratio of Democratic to Republican professors to be extremely high (that is, higher than a 10:1 ratio) were 24 percent more likely to distrust academic knowledge claims than those who perceived the ratio to be even (1:1). The 39 percent of the sample that had a relatively accurate perception of the D:R ratio, ranging from 2:1 to 9:1, were 14 percent less likely to trust academic knowledge claims than were those who perceived the ratio to be even. [3]

An analysis of this sort, with these types of survey data, cannot demonstrate conclusively what is causing what. We can’t be sure that distrust in academic knowledge claims is driven by perceptions of the parstisanship of those making the claims. All that’s clear is that partisan identity, perceptions of the ideology and partisanship of faculty, and distrust of academic knowledge claims are strongly interconnected. And it does seem plausible, though, that, inasmuch as Republicans and conservatives see academics as members of the opposite party and adherents of the antagonistic ideology, they would distrust their knowledge claims, just as Democrats and liberals distrust the knowledge claims made, for example, by employees of the Heritage Foundation.

A Rejection of Certain Scientists, Not of Science Itself

Scholars often assert that their ideology does not affect their conclusions. Yes, they say, they cluster on one side of the political spectrum, but their training and methods overcome any ideological bias. Fewer and fewer Americans are likely to believe it. Distrust of partisan motives and of the opposing ideology seems to be the tenor of the times, and it should be no surprise that this extends to scholars.

Therefore, it may be important to distinguish between distrust of science as a method of knowledge generation and distrust of academics as a group of people practicing it. Conservatives could distrust both science and scientists, or trust science but distrust scientists (especially social scientists).

In a detailed study of public trust in science over the past four decades, Gordon Gauchat argues in the American Sociology Review that “the credibility of scientific knowledge is tied to cultural perceptions about its political neutrality and objectivity” (168), and he demonstrates a clear relationship between political conservatism and lack of trust in scientists. But he does not distinguish between the two possible sources of distrust—the methods or the practitioners, science or scientists. More pointedly, Chris Mooney argues that the source of conservative distrust is clearly a rejection of science as a method. But the survey data suggest the opposite: a rejection of the practitioners. The Pew graph shows a dramatic change in just a few years, which would mean that if Mooney is right, conservatives suddenly decided to abandon science, which seems unlikely. Tables 1 and 2 suggest a much more plausible explanation for the Pew numbers: a sudden burst of publicity indicating left-wing ideological homogeneity on campus.

The distrust described above and that discussed in Part I—distrust of traditional news media—is unquestionably driven by conservatives. Referring back to the Gallup chart in Part I, trust in media is lower and falling faster among Republicans. (Trust is also falling somewhat among Democrats, but remains relatively high). The rise in distrust of academia is also entirely a province of the right. But there is no evidence of a general decline in conservative trust in epistemic authorities. The distrust targets only the epistemic institutions controlled by the left. Conservatives have abandoned academe because they perceive it to have abandoned them.

The dominance of liberal faculty is real—even more so than most conservatives realize, according to our data—which suggests that as long as the conservative media continue to publicize what’s happening on campus, conservative voters will continue to distrust academic experts.

The Realignment of Epistemic Authority

The rejection of both the media and the universities as sources of knowledge can be described as a realignment of authority. Unlike previous political realignments, which revolved around partisanship or issue positions, the realignment of authority is grounded in a collapse of trust in institutions of knowledge creation and dissemination that previously enjoyed consensual deference.

Liberals have maintained their trust in traditional epistemic authorities, but is this because they have a deep commitment to science or because they agree with the scientists?

A new study in Social Psychological and Personality Science suggests that contrary to the common view that liberals agree with science on principle, “liberals and conservatives appear to be similarly motivated to deny scientific claims that are inconsistent with their attitudes.” The researchers created data presentations on such issues as gun control, health care, same-sex marriage, and immigration, which could easily be interpreted one way, but really indicate the opposite when closely examined. When shown these data and asked what they suggest, both conservatives and liberals interpreted the evidence as favoring their initial attitudes. When errors of interpretation were pointed out, both sides deeply distrusted the results that disconfirmed their preferences. Liberals rejected inconvenient evidence at the same rate as conservatives did.

Liberals clearly show greater support for universities, but it may not be respect for institutional authority alone that is keeping their allegiance. I suspect that the mood of populist epistemology and disregard for expertise is a national phenomenon, not just a conservative one. While the movement away from consensus facts grounded in established authority is dramatic on the right, it may be latent on the left.

The Problem of Inconvenient Expertise

There are now and have always been those who are fundamentally uninterested in facts or details. “I am sure that I never read any memorable news in a newspaper,” said Donald Trump in 1994 in an interview. No, it was actually Henry David Thoreau in Walden (1854). That peculiarly American believer in his own perceptions was famously uninterested in news from journalists or facts from experts, but was sure he could feel his way to Truth. “Sometimes, when I compare myself with other men, it seems as if I were more favored by the gods than they, beyond any deserts that I am conscious of; as if I had a warrant and surety at their hands which my fellows have not.”

As Americans, our relationship with institutionally endorsed facts over personal knowledge is rocky at the best of times and is clearly fractured now. A consistent acceptance of inconvenient expertise is a rare position. It would dictate that the right accept the existence of climate change, and the left accept that a $15 minimum wage has negative effects and GMOs are not harmful. The powerful cocktail of forces described above makes this unlikely:

- The confusion of truth and facts.

- The death of conservative trust in mainstream media.

- The death of conservative trust in universities.

- And the rise of a populism that encourages all of these effects.

Max Weber argued that “the primary task of a useful teacher is to teach his students to recognize ‘inconvenient’ facts—I mean facts that are inconvenient for their party opinions” (“Science as a Vocation”). Sadly, the teacher cannot perform this task if he or she is distrusted because of his or her political views. Nor can the teacher inform society of new knowledge if he or she is viewed with suspicion. Now that the partisan and ideological imbalance in the universities is becoming known to ordinary citizens, the same suspicion that is causing distrust in the media is causing distrust in academics.

Morgan Marietta is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. He is the author of A Citizen’s Guide to American Ideology: Conservatism and Liberalism in Contemporary Politics, The Politics of Sacred Rhetoric: Absolutist Appeals and Political Influence, and A Citizen’s Guide to the Constitution and the Supreme Court: Constitutional Conflict in American Politics. With David Barker, he is currently writing One Nation, Two Realities: Dueling Facts in American Democracy (Oxford University Press), on the causes and consequences of polarized fact perceptions.

NOTES

¹The first set of questions was included on the 2013 CCES. The second survey was conducted by YouGov in April of 2014, sponsored by the Center for Public Opinion at UMass Lowell. Each survey queried a national stratified sample of 1000 respondents, conducted via Internet polling by YouGov, which interviewed an oversample of respondents (1172 in April 2014) which were then matched down to a sample of 1000 to produce the final dataset. The respondents were matched to a sampling frame replicating the U.S. population in gender, age, race, education, party identification, ideology, and political interest.

² These figures average the results of three recent studies of academic ideology: Rothman et al. (2005), Hurtado et al. (2011), and Gross (2013).

Rothman (employing 1999 data) reports 72 percent liberal and 15 percent conservative faculty (4.8:1); Hurtado (employing 2011 data) reports 63 percent liberal and 13 percent conservative (4.8:1); Gross (grounded in a 1996 survey) finds 63 percent liberal, and 20 percent conservative (3.2:1). Average results are 66 percent liberal and 16 percent conservative, or a ratio of 4.1:1. (If we average the ratios rather than the liberal and conservative percentages, the result is 4.3:1). These numbers are averages across the university; within disciplines like political science or especially sociology the ratios are much higher.

³ This analysis employs a logistic regression, which is designed for dichotomous dependent variables, in this case whether citizens perceive the university to be more likely correct or incorrect. This statistical approach can provide the change in the probability of one outcome over the other (distrust rather than trust) in response to specific independent variables of interest, in this case perceptions of the partisan balance of university faculty, controlling for a range of other possible influences, such as age, gender, income, education, and political knowledge of the respondent, each of which demonstrated an indepdendent statistically significant relationship (N=989).