Britain’s shocking vote to leave the European Union has renewed discussion about the compatibility of open migration and the welfare state. Yet for Europeans, it is a discussion that has been going on for years.

The core fear of immigration-inspired Brexit voters is not that a Polish migrant will steal a British job. Rather, it’s that the 110 million new people who joined the EU’s single market following the Eastern European enlargements of 2004, 2007, and 2013 will find low-skill jobs that satisfy the minimum requirements needed to become eligible for the full suite of British public services, as required by EU law, and thus become a net fiscal drain on the public purse.

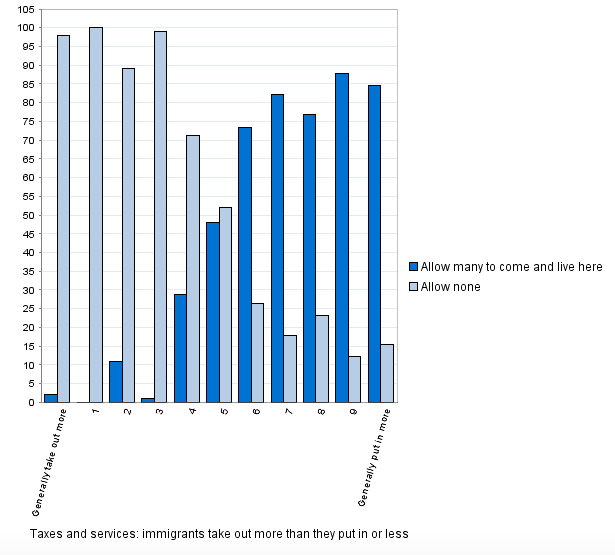

Indeed, the European Social Survey, clearly indicates the perception that “immigrants take out more than they put in” is by far the dominant issue affecting negative views of immigration. That’s why Brexit campaign slogans called for reinvesting British dollars back into public services, and why David Cameron spent enormous political capital renegotiating the rules around access to benefits.

UK respondent’s views on whether they should allow more immigration from poorer European countries hinges on the perception of net fiscal impact. Source: ESS 2014

Markets Handle Immigration Better Than Governments

This makes defending open migration much more challenging than simply pointing to the lump-of-labor fallacy, or the strong empirical evidence that migrants do not drive down wages, since the problem isn’t with the market. If anything, the EU’s experiment with free movement demonstrates that markets and the price system handle open immigration incredibly well. Markets spur new construction, match workers to jobs, induce human capital formation, reward assimilation and entrepreneurship, and so on and so forth.

The problem is with governments. Poorly designed or out-of-date public policies really can make new migrants a net fiscal burden, by taking out more in social benefits than are put back in through taxes. This in turn can have the perverse effect of delaying labor market integration, or even create a two-tier society.

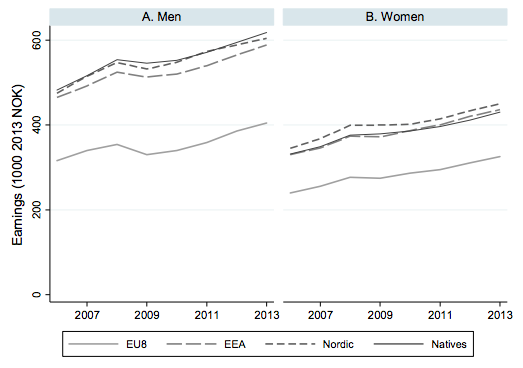

Take Norway, which, while not in the EU, is fully integrated in the EU’s free movement rules as required for access to the single market. Norway has experienced much higher rates of EU immigration than the UK in proportion to its population, largely because of more generous social benefits, including family allowances. As two IZA researchers, Bernt Bratsberg and Knut Røed, point out,

For families with children, this entails that a job in Norway may be attractive even if the offered wage is extremely low. For example, the Norwegian cash‐for‐care subsidy for a one‐year old child now amounts to NOK 6,000 per month, which adjusted to the 2010 wage levels and exchange rates used in Table 1 corresponds to 629 Euros, or around 80 percent of average earnings in Poland. Such features give employers and prospective immigrant employees incentives to agree on very low wages and poor working conditions. While this can be a win‐win situation for the employer and the immigrant worker – at least in the short run – it may stimulate the creation of poor jobs with high subsequent unemployment or disability risk and substantial (expected) costs for the welfare state.

This is reflected in persistently lower earnings for immigrants from the EU8 (Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia):

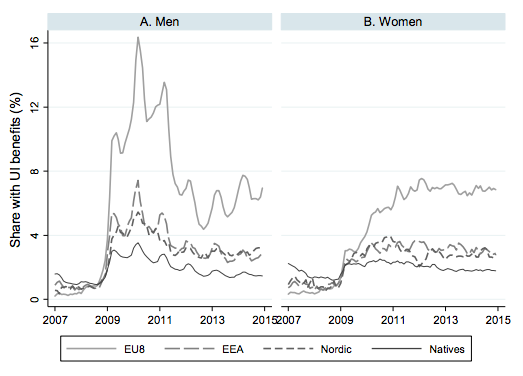

And higher reliance on unemployment insurance:

The UK has worker and child tax credits that works similarly, of which 17% percent of claimants are not UK nationals. This doesn’t mean open migration in the EU can’t work; it’s just a much tougher problem than some are portraying it to be since it depends crucially on responsive and intelligent welfare reform by governments. As the Niskanen Center’s namesake, William Niskanen, once put it: “Build a wall around the welfare state, not around the country.”

That’s essentially the approach the United States has taken ever since the 1996 welfare reform restricted migrant access to most welfare programs. Unfortunately for Europe, it’s not so easy, as members are required to treat internal immigrants like any other native worker. The solution is therefore a related but slightly modified idea: make the welfare state migration robust.

According a 2015 paper by economist Martin Ruhs, that means ensuring social insurance systems lean toward being contributory rather than noncontributory. Contributory social insurance refers to any benefits that are only paid if the beneficiary has made a prior contribution. This automatically favors individuals who have lived and worked in the country, independent of citizenship.

Changing Perceptions

The United States, however, is not so constrained politically. Despite its many flaws, the current U.S. welfare system is far more robust to low skill immigration than Europe’s. In fact, there is basically no evidence of “benefits shopping” between states, which has occurred between EU member states. Yet there is still room for improvement. Alex Nowrasteh and Sophie Cole of the Cato Institute, for example, have suggested some practical reforms to reduce non-citizen access to means tested programs like SNAP and Medicaid. Contributory schemes should, of course, remain fully available.

So if there’s any lesson from Brexit for proponents of greater immigration to the U.S., in which I include myself, it is this: even when immigration is a clear net benefit to the economy, there is a very serious potential for backlash and even policy reversal if the public perceives migrants to be a net fiscal cost. Minimizing that perception, even if it is only a perception, is therefore paramount.