“The Permanent Problem” is an ongoing series of essay about the challenges of capitalist mass affluence as well as the solutions to them. You can access the full collection here, or subscribe to brinklindsey.substack.com to get them straight to your inbox.

I want to follow up on my last essay with some further observations about our toxic media environment. Specifically, I’d like to flesh out my argument that mainstream media bears some responsibility for its loss of credibility among large sections of the public. First, I want to give a fuller account of where it went wrong. And second, I want to offer a more complete explanation of why it went astray. I argued that competitive pressures pushed it in the wrong direction, and that’s true – but there’s more to it than that.

As I mentioned in the last essay, trust in the news media has fallen sharply over the past half-century. Back in 1972, 68 percent of Americans reported “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the mass news media, while only 6 percent reported “none at all”; in 2022, those figures stood at 38 percent and 28 percent, respectively. Until Trump arrived on the scene, trust fell across the board, although the gap gradually widened between Democrats and everybody else; since 2015, though, Democrats’ trust levels have soared back to 1970s levels while independents’ trust levels continued falling and Republicans’ collapsed.

(Just as an aside, I think it’s interesting that poll respondents are clearly focusing on the “mainstream media” here, not the newer right-wing media ecosystem anchored by Fox News. Otherwise, we would expect Republicans to register some approval of now having a conservative option, and Democrats to downgrade the media’s overall performance because of Fox’s prominence.)

There’s one obvious explanation for the ongoing evaporation of trust on the right: Republican politicians and conservative commentators have been complaining bitterly about liberal media bias since before I was born, and with increasing intensity and vituperation over the course of my lifetime. This incessant campaign was intensified dramatically with the steady build-out of the right-wing media counter-establishment – starting small with low-circulation magazines like National Review and Human Events, then developing a mass audience with talk radio, then expanding the mass audience through cable news and the internet. If you saturate that audience with resentment and distrust for decades, it’s going to have an effect.

That’s an important part of the story, to be sure, but it’s not the whole story. In addition, I believe that mainstream news organizations bear some responsibility themselves for their diminished standing. Journalism once enjoyed authority as a trusted source of information that both sides could rely on. But authority isn’t something you’re born with, not since we scrapped the whole divine-right-of-kings business. Authority must be developed, earned, and maintained. As journalism strove to rise above its partisan and yellow press origins over the first half of the 20th century, news organizations and professionals took considerable care, both in how they operated and how they presented themselves to the world, to build trust and burnish their own authority. But in recent years, even as institutional authority and social trust have come under serious challenge in virtually every domain of American life, journalism has increasingly forsaken the practices and self-discipline upon which its authority rested.

The authority of mainstream journalism wasn’t just toppled by a concerted external attack. It was also abdicated.

Look at any source of institutional authority in society, and you’ll see concerted efforts to distinguish that institution and its members from everybody, to set them apart and show that they are special – and thus deserving of special respect and deference. Priests wear a collar, and once spoke in Latin while wreathed in incense. Police wear a uniform and a sidearm. Judges wear robes, sit above everybody else, and expect everyone to rise when they enter a room. Doctors sport the white lab coat and take umbrage if you call them Mr. or Mrs. This public presentation of a special role in society is important.

Over the 20th century, journalists worked assiduously to raise their status in society above their lowly, somewhat disreputable origins as “ink-stained wretches.” Columbia University’s School of Journalism was created, and the Pulitzer Prizes were established. The American Society of News Editors was founded.

Journalism’s central strategy for raising its professional status and position in society was the enshrinement of objectivity as its core commitment. Before getting into whether objectivity is actually desirable, or even possible, let’s understand why this particular value was elevated as journalism’s pole star. The purpose was to establish and buttress the fledgling profession’s position in a central and vital social role – as a trusted source of information about public affairs. And to be considered widely trustworthy in the sprawling, bumptious pluralism of modern society is not an easy trick to pull off. It requires special discipline and focus.

In particular, the commitment to objectivity means that journalistic accounts must always hew closely to verifiable facts – who, what, when, where, and how. Why is much trickier, as there’s frequently deep and unresolvable disagreement about that. Here the best that can be done is to make the public aware of what the leading interpretations are and how they differ. So while analysis and commentary have always been a part of journalism, the heart of the enterprise – the basis for journalism’s claim of authority – is accurate reporting of carefully established facts.

To convince the public of journalism’s central commitment to verifiable facticity, journalists themselves must embody – and be seen to embody – the virtues appropriate to their role. They must build a reputation for insisting on verification and corroboration: “If your mother tells you she loves you, check it out.” And they must take special pains to set themselves apart from the action they cover – to be neutral observers, not active participants. Since passion and interest are the main sources of factions in society, and of controversy among contending factions, journalists need to model dispassion and disinterest. They must avoid sensationalism and appeals to emotion, and they must avoid taking sides.

In this old 20th century model of objective journalism, the pose of cool-headed neutrality was taken seriously. It meant staying away from organized political activity, or even sharing your political opinions publicly. Some carried things even farther, refusing to join a political party or even vote in order to preserve their outsider status.

I recognize that this little recitation sounds musty and old-fashioned – and that’s a good clue as to what’s gone wrong. In these postmodern times, the whole idea of objectivity has come under sustained attack. For one thing, psychology and behavioral economics have found that we are riddled with cognitive biases that regularly distort our assessment of what’s going on.

But while the limits of individual human rationality are a fascinating area of study, they really are beside the point here. Even if we can never reach the bedrock of ultimate truth, we can all judge degrees of accuracy: There’s all the difference in the world between a conscientiously reported account of events on the one hand, and loose innuendo or outright fantasy on the other.

Beyond these concerns about individual human fallibility, there is the political critique of objectivity as a mask for power. According to this line of argument, journalistic neutrality isn’t really neutral; it’s an implicit decision to side with the powerful. Reporting a controversy, and the various sides of that controversy, without finally declaring who’s right and who’s wrong is an abdication of responsibility. If you’re really going to serve the truth, you need to take sides.

This political objection to objectivity has gained considerable ground within the profession in recent decades, with fateful results. The objection, in my view, rests on a massive confusion concerning journalism’s role in society. It may flatter some journalists’ egos for them to see themselves as arbiters of truth, but news reporting has no capacity or authority to fulfill that role. Its actual job, much more modest but nonetheless critical, is to provide society with an agreed-upon set of facts to guide public debate. And you can’t fulfill that role if you take sides on controversial issues, because those on the other side won’t trust you.

Journalism is already vulnerable to distrust because its practitioners are drawn so disproportionately from the left side of the political spectrum. There isn’t much that can be done about this: The simple fact is that the type of people for whom journalism holds appeal as a career – people who are good with words and more interested in ideas than money-making – skew overwhelmingly left. Moreover, in an age where self-expression values are dominant, authority of any kind is increasingly on the defensive. Under these circumstances, the profession was well advised to double down on objectivity, not back away from it.

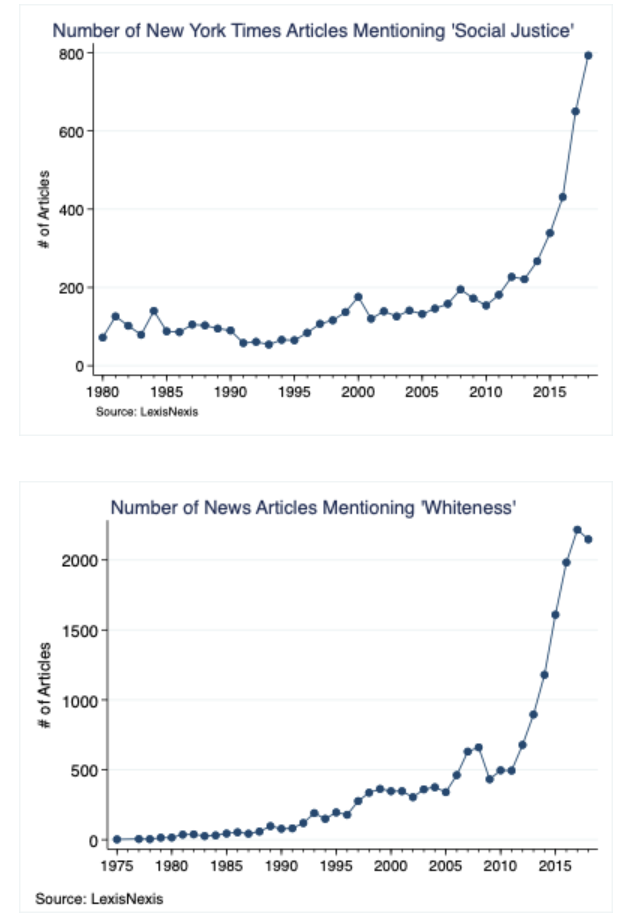

Alas, backing away is what happened. In part it happened because of ideological changes on the left. As politics has grown more performative, and taking public stands on behalf of approved causes has become the benchmark of political virtue among those under the performative spell, many journalists were understandably swept along with the tide. The New York Times’s 1619 project is the most well-known example here, but the newspaper’s overall coverage shifted markedly in line with the past decade’s various social justice-themed enthusiasms. The charts below illustrate the trend:

Meanwhile, as social justice activism roiled the internal workings of professional organizations across the board, newsrooms were no exceptions. Here again the New York Times was on trend, with a staff revolt leading to the ouster of the editorial page editor for running an op-ed by a Republican senator in favor of using the military against rioters. Whatever they thought they were accomplishing, the increasing outspokenness of journalists on behalf of their political beliefs has played directly into the hands of right-wing assaults on the mainstream media. Those attacks on “fake news” portray the media as left-wing partisans masquerading as journalists, and the subjects of those attacks were only too willing to supply ammunition.

To be fair, the rise of Trump did represent a genuinely difficult dilemma for journalism. What do you do when you’ve become the story – when the president of the United States is actively vilifying and demonizing you? What do you do when the president lies constantly, extravagantly, gratuitously, about matters great and small? The traditional style of objectivity, developed in less disordered times, included a strong tendency to treat both sides as acting in good faith and representing reasonable alternatives. But instead of the usual clash of two parties operating within the system, now the leader of one party was – in a wide variety of ways – actively undermining the system. The old assumptions and framing did not seem suited to the times, but how far to go in defending the media against attack and in presenting Trump as a unique and unprecedented threat? I don’t pretend that there were any easy or fully satisfactory answers.

Returning to the argument of my last essay, there was a third factor besides ideology and Trump that drove mainstream journalism to abandon the high ground of objectivity: money. Trump was a ratings bonanza for cable news, and digital subscriptions to the New York Times and the Washington Post tripled during his time in office. CNN exploited the situation coming and going: first building up Trump with nonstop coverage, then presenting itself as the vanguard of the resistance once he won. Along with MSNBC, it enjoyed record ratings and profits. The Washington Post leaned into the demand for overt media opposition to Trump with its new “Democracy dies in darkness” slogan. Reporters for the Times and the Post became media celebrities with their regular appearances on cable news talk shows. Media figures more generally raced to build their personal brands by developing large followings on Twitter, where the currencies of the realm are righteous indignation and pugnacious snark. However careful and well-sourced their actual work, many reporters have been actively presenting themselves to the world, not as neutral observers, but as active participants in the political drama.

So here we are. Although I believe that mainstream journalism’s missteps in recent years have been real and consequential, I don’t want to overstate those consequences. If all the major media organizations had conducted themselves more circumspectly and reined in their employees’ public-facing moonlighting, my guess is that their trust numbers would look somewhat better, but that the general trend would still be the same. The right-wing attack has been too sustained, and recently too virulent, for any other outcome to be possible.

However we got here, the situation is dire. We’re the richest, most powerful country in the world. We have miraculous information technologies that put virtually all the world’s knowledge at our fingertips. If you want to be well-informed and you know what sources to trust, there has never been anything remotely like the current access to excellent reporting around the world and superb commentary and analysis. Yet large sections of the American public believe that the 2020 election was stolen and that Covid-19 vaccines are bad for you. And because of that latter delusion, hundreds of thousands of Americans are dead.

How do we get to something better? There’s no going back to information scarcity – and we shouldn’t want to. I don’t imagine we can ever return to a culture of broad-based deep literacy, however much we might want to. And especially under these contemporary conditions of information overload and mass audiences unable to tell the difference between well-established facts and arrant nonsense, a free market in news seems destined to bring out the worst in us. In a no-holds-barred competition for eyeballs, the race belongs to the most irresponsible.

In the short to medium term, our best hope – and it’s just a hope at this point – is that the currently dominant performative style of culture-war politics will burn itself out before it burns down our republic. If the main political divisions were no longer along demographic (and especially educational) lines, mainstream journalism would not be so clearly identified with one of the two warring tribes. And if journalists themselves became less politically homogeneous, the temptation to trade in objectivity for activism would be diminished.

Over the longer term, though, if we are ever to achieve an informational environment that is suitable to our level of technological and organizational complexity, I believe that fundamentally new institutions and approaches will be required. I will be writing more on this in due time, but for now I’ll offer just a couple of thoughts. First, we need new nonprofit news organizations, constituted to serve the public and devoted exclusively to factual reporting of public affairs, without analysis or commentary. Reporters who work for these organizations need to be bound by a strict code of professional ethics that clearly distinguishes them from the rest of the media universe. Second, we need the equivalent of the temperance movement for media consumption – a broad-based, bottom-up campaign to convince people that heavy, indiscriminate consumption of commercial and ideological news media is dangerous to their intellectual and moral well-being. In a free society, we can’t stop people from saying stupid and hurtful things, but we can certainly do a better job of teaching the rest of us to tune them out.