Few incidents short of wars can test national systems of government as sharply and clearly as COVID-19 has done. Debate about the value of any given social system typically happens at a high level of abstraction, with arguments over guiding ideals or, at best, occasional and widely disputed attempts at measurement of outcomes like economic growth or inequality. Rarely does such abstract and theoretical disputation yield a once-and-for-all conclusion as to whether the government is fit for purpose. We argue endlessly over the relevance of income growth, given all the accompanying environmental externalities, or the relevance of various measures of inequality, for instance. But with this crisis, few can dispute that more than a million American deaths from COVID-19 and years of serious economic disruption add up to failure. That the U.S. failed COVID’s test is even clearer when the American experience is compared to that of peer countries: America’s cumulative COVID death toll per capita is the highest of any rich democracy, and higher than that of many poor countries with much less advanced economies. What went wrong in the U.S. response to COVID?

The two of us were deeply involved in a major effort in the spring of 2020 to put the country’s pandemic response on the right track after its initial stumbles. Our recommendations were ultimately rejected by the Trump administration, and shortly thereafter the federal government effectively withdrew from trying to manage the crisis at the national level — with the important exception of the Operation Warp Speed program to accelerate vaccine development.

Here we will focus our analysis on the initial phase of the pandemic — i.e., prior to the availability of vaccines at the end of 2020. This is the period when we were actively involved and about which we can speak from direct experience. There is much to be said about the successes and failures of vaccine development and distribution, and the proper role for various mandates and restrictions once vaccines became freely available, but we will leave that to others. We want to address why the United States was unable to contain and suppress the virus, and thus why some 350,000 Americans died before vaccinations started in earnest. In particular, we want to understand why the United States failed while a number of other countries — countries that virtually everyone would have assumed at the outset of the crisis were less well-positioned than the United States — succeeded in keeping fatalities to a minimal level and saving their economies from traumatic shutdowns.

The story of the U.S. failure to meet the moment back in 2020 is a tale of well-intentioned experts falling into the traps of technocracy; politicians calculating primarily about electoral gains; and a polarized public seeing every fact as either a rabbit or a duck depending on how partisans squinted — leaving politicians no room for compromise.

The U.S. response to COVID: What would success have looked like?

In the U.S. back in March and April of 2020, public debate focused on a choice between lockdowns to preserve public health and opening to revive the economy. This was a fruitless debate. The international experience largely belied any such tradeoff. The countries that performed best on public health also suffered the least economic damage. Even well-run countries like Sweden that chose to favor their economies over public health by avoiding lockdowns failed to spare their economies. Sweden suffered a downturn as severe as neighboring Norway and Denmark, and many more deaths.

The fundamental error that led us into the interminable discussion of a tradeoff was to conceive of lockdowns as a primary policy lever in addressing the crisis. In fact, lockdowns were not an active policy themselves but mostly an unavoidable and largely organic response to failed policy — namely, a failure to have suppressed the disease in the first place. Lockdowns are like putting a patient into a coma to prevent immediate death, not like a treatment.

Successful countries understood this and from the start pursued policies of disease suppression that were quite different from the path pursued in the U.S., with five key and consistent elements:

- Internal and especially external restrictions on travel from areas of community spread.

- Universal wearing of high-quality masks in shared spaces.

- Restructuring of shared spaces and especially public space to allow distancing. The most challenging aspect here was restructuring of spaces to accommodate a wide range of socioeconomic classes, rather than just reducing density and rationing with price in ways that allowed the rich to carry on while excluding the poor.

- Programs of testing, contract tracing, and “supported isolation” (TTSI) that allowed the disease to be eliminated from community circulation. TTSI programs were both the most consistent and consistently successful element among the countries that responded effectively, and one that varied in many details given technical complexities across locations. We have written extensively elsewhere about TTSI strategy and will not belabor it here, but the key idea is to use testing to seed a process of tracing contacts that turns up additional cases. All identified cases are induced to isolate until they are no longer transmitting the disease. Contact tracing is accomplished through a mixture of human intelligence, interviews, and digital recording technology. Privacy-attentive and effectively interoperable data systems are critical to achieving this.

- Rapid adoption of the previous four methods and consistency in maintaining them.

Every country that was highly successful in combating the virus used some configuration of these approaches, though details, especially of precisely how TTSI played out, varied greatly. These five policies taken together did not harm the economy but rather mobilized it to fight the virus. In some cases, these measures were complemented by short lockdowns used as time-buying measures, but not as the primary instrument of policy. Taiwan, New Zealand, Australia, and South Korea all discovered this simple and clear formula for victory over COVID-19. What’s more, they had already discovered it by the end of February 2020, when serious crisis response was still getting underway in the U.S. The answer was already sitting right there across the Pacific.

In this country, too, experts eventually found and built on that example and rendered the winning playbook in English, tailored to the U.S. context. Our research network, the COVID Rapid Response Initiative at Harvard’s Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics, published that playbook on April 20, and the Rockefeller Foundation published a closely aligned playbook the following day. Our playbook recommended that the White House establish a Pandemic Testing Board on the model of the World War II Production Board to rapidly ramp up diagnostic testing capacity. An alternative to a Pandemic Testing Board, we suggested, could be investment in interstate compacts that would do this work.

We had taken too long to discover and publish the playbook but even so, something worse was still to come. The country failed to adopt it. As a result, some 350,000 people died in 2020, before vaccines went into wide distribution. In Australia, which has 1/13th of our population, only 909 people died that year. Had we had an equivalent level of success to Australia in suppressing the virus, we would have had a death toll of roughly 12,000.

The technical knowledge of how to fight COVID existed in the world by the end of February. It existed in the U.S., tailored to our context, by the middle of April. We didn’t fail for lack of knowledge. Our failure, in other words, wasn’t technical. It was organizational and political. Everybody played a role: technocrats, politicians, and the public. Honesty requires acknowledging that we failed together.

“Healthy people should not wear masks:” Where technocrats went wrong

In January, February, and March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was flailing. They had bungled the original effort to get diagnostic testing off the ground in January and had sent out flawed tests to labs across the country. Then they spent a month and a half offering perverse advice about masking.

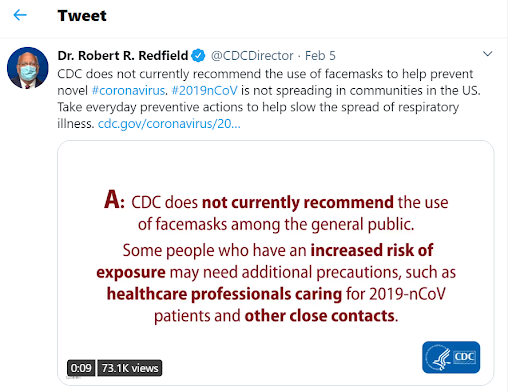

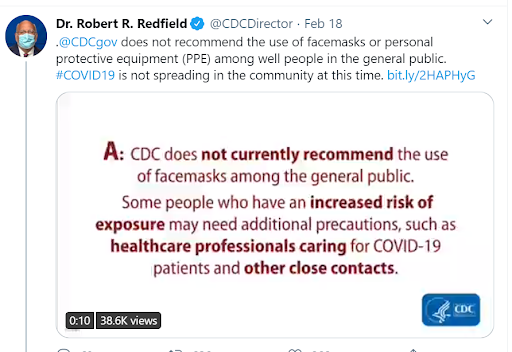

In February, for instance, the CDC posted the following guidance on its website: “If you are NOT sick: You do not need to wear a facemask unless you are caring for someone who is sick (and they are not able to wear a facemask).” The site went on to say, “Facemasks may be in short supply and they should be saved for caregivers.”[1]

The CDC worked hard to get this message out. Director Robert Redfield tweeted on February 5 and again on February 18 that the CDC did not recommend use of facemasks.

On February 28, at a congressional hearing, Redfield was asked, “Should healthy people wear face masks?” His answer was, simply: “No.”[2]

By this point in time, the countries that had experienced earlier outbreaks of COVID — including China, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand — were all broadly encouraging general masking. For that matter, the guidance that even healthy or asymptomatic people should wear masks had already become routine for an airborne infectious disease with the SARS epidemic in 2003, an earlier coronavirus epidemic. The wrongheaded and deadly CDC guidance on masking captures in one plot point all that was wrong with the technocratic approach unfolding in the U.S. response to COVID.

The country needed its COVID response leaders to take a broad view by first articulating a national goal — for instance, that we should suppress COVID while securing the economy. Then, communication of that national goal should have been followed by a set of clear technical tactics for achieving it. Instead of providing expert advice within a framework of this kind, however, the CDC decided to “stay in its lane,” offering largely reactive advice on narrow questions specifically posed to it by the White House. The question that Director Redfield was answering in Congress, which generated the masking guidance, was in fact the very narrow question of whether the public should wear N95 masks, the only grade of mask that can comprehensively block the intake of incoming particles from another person, in addition to preventing the emission of particles by the mask wearer. Those masks were in short supply and did indeed need to be reserved for health care workers. It was those masks specifically that Redfield had in mind when he said that the public should not wear masks. He was not answering the question: “What role should masks in general play in a strategy of COVID-19 suppression?” He was answering only the question, “Should members of the general public wear N95 masks?”

The question of what health care workers needed was important, but only one part of the puzzle. The full puzzle, properly understood, was how to suppress COVID while securing the economy. But this question was so far from the Director’s radar screen that he and his colleagues at the CDC were unable to see how narrow and limited their answer to questions about masking was and how inappropriate their guidance was to the moment we faced.

The harm done by the narrow approach taken by the CDC was not merely that it failed to see the larger strategic question, answering only one narrow tactical question and then presenting that answer as if it were a broader strategic answer. The greater harm was that the ineptitude and inaptness of its guidance thoroughly undermined its authority as a purveyor of useful answers based on well-reasoned consideration of the evidence. Rather than frankly explaining the somewhat subtle issue of the strategic role of masking to the public and calling for thoughtful rationing procedures as adopted in every successful country, the CDC talked down the broader benefits of masking and emphasized the uncertainties around mask usage. By the time it reversed its position in April, the CDC had created enough doubt and confusion in the minds of the public about the value of masks that achieving the breadth of mask adoption seen in the most successful countries was probably already out of reach. Of course, the president’s refusal to wear a mask would soon make the situation much worse, but the CDC had already sown the seeds of doubt.

The failure of the CDC to see and respond to the big strategic question — how to suppress COVID while securing the economy — was mirrored by economists, who tended to assume that the only way to secure the economy was to give up trying to suppress COVID. The misguided debate about a tradeoff between protecting health through lockdowns or the economy through opening up was often cast as an argument about whether we should listen to public health experts or economists. But this is the wrong way to think about the role of expertise in strategic decision-making. Public health experts had only part of the answer. They know how to fight diseases. Similarly, economists had only a separate part of the answer. They know how to keep liquidity flowing or how to stimulate a sinking economy or how to reorganize production and supply chains.

Public health experts in February had no reason or training to ask questions about political economy, such as: Can this economy in a compressed time period deliver a testing infrastructure such as this country has never seen before? With no reason to ask that question, public health experts had no reason to try to imagine tools of disease response that would depend on that kind of economic capacity. Most public health officials knew little about the economics or technology around dramatically and rapidly increasing test capacity. They quickly and wrongly assumed that building testing capacity to a level useful for disease suppression was logistically and/or politically infeasible. Thus, as with masks, they adopted something of a zero-sum mentality, where tests used for disease suppression would be taken away from potentially life-saving therapeutic applications. On the other hand, they assumed that lockdowns would be much more legitimate and consistently applied than they were. They thus focused their attention on these and largely elided or ignored the testing issue and never clearly communicated to leading policymakers, including those in the White House, the scale of testing required for disease suppression or the inevitability of extended or repeated lockdowns if this scale was not reached.

When our research group met with CDC analysts in late March and early April, we would ask them what their models showed about how much testing would be needed to suppress COVID and keep the economy open, if we followed the playbook from South Korea. They would answer by saying that they too had been wondering that but that none of their higher-ups had asked that question. They then did back-of-the-envelope calculations for us and came out roughly where we had in their analysis of what was necessary. Those numbers were big — 5 million tests a day, at a point when the country was doing only 100,000 tests a day — but that shouldn’t have scared us off. It just meant that we needed economists in the conversation who could help us answer the question of how to rapidly transition production.

On the other side of the fence, though, economists had no reason or training to ask questions like: Is there by any chance a tool for disease control other than collective stay-at-home orders that might be less damaging to the economy? Economists generally don’t ask questions about how to solve public health problems. Public health experts don’t ask questions about how to transform the structure of supply chains. There was a pressing need to integrate the policy space, to take in advice from experts in each area but then to make big-picture judgments. Our failure to achieve this reveals our need to shake off the shackles of deference to technocracy. Our leaders should have led us in the process of asking the right questions, and then making judgment calls, taking into account the best advice that experts could give but recognizing that all experts can do is give advice. It’s the job of elected leaders to see the integrated problem and find the integrative solution.

Technocrats went wrong by staying in their narrow lanes, rather than seeking to direct their expertise toward the most important, overarching strategic question. But then again, we can’t really blame them, as they should properly be simply advisors to decision makers. It is the decision makers, the elected officials and policymakers, who have the job of asking the overarching strategic question and then weaving together the different kinds of expertise needed to deliver an answer. If the technocrats failed, then that’s because the politicians did not put them to work appropriately. Why not?

Politics above all: Where politicians went wrong

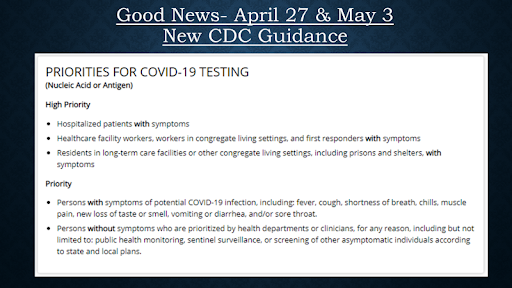

On April 27, 2020, the stars of the American political universe briefly aligned. On that day, both the Trump administration and the Biden campaign released plans emphasizing the importance of a massively scaled-up testing supply chain in response to COVID-19. Both plans proposed to put testing and contact tracing to work in fighting COVID. In addition, on the same day, the CDC at long last changed its guidance to support testing of asymptomatic people — that is, people who had been exposed to the virus but showed no symptoms. By the middle of April, we knew that about 50 percent of the transmission of COVID was occurring via infected people who either had no symptoms or who had not yet developed symptoms. This change of testing guidance was crucial, because it meant that the CDC had finally recognized that COVID testing had two purposes. It was needed not only for diagnosis and proper therapeutic treatment of people arriving in hospitals; it was also needed for finding the virus wherever it was, even when it was thriving in hosts without symptoms. They had finally recognized that we needed not only therapeutic testing but also widespread screening testing.

For those of us who had been advocating for the previous six weeks that the country should massively scale up its investment in the successful TTSI playbook of testing, contact tracing, and supported isolation, the simultaneous announcements of plans that aligned with that playbook from both the administration and the opposition looked like news to celebrate.

What fools we were. That day was the last time the Trump administration made a significant public push on testing. It was actually the beginning of the end of any real chance the country had for defeating COVID. Because of politics.

In 2020, politics trumped all. If technocrats were answering only narrow questions, rather than more broadly pursuing the most important strategic question, the same was true for politicians. The CDC had been myopically focused on the question of what health care settings were needed to deal with patients presenting with COVID, rather than pursuing the broader question of how we might control the disease. The politicians were just as myopically focused. Their aperture of analysis had been narrowed to the question: “How am I most likely to win this upcoming election?” Our research team sought many avenues — formal and informal — to contribute our advice about the winning playbook to the White House Coronavirus Task Force and to the president himself. Along every informal path we traveled, we were given the same advice. Present your case from the point of view of how it will help the president win reelection.

The Biden campaign was equally focused on winning the election, even if less willing to say so quite as openly. In our starkly polarized landscape, it was politically impossible for the Trump administration to adopt any idea that was pre-stamped with approval by Joe Biden. This was an obvious political fact. This meant that if the president was going to adopt the right idea, he also needed to be able to claim credit for it. In April, a decision-making focus on the good of the country required giving the president the space to be the first to adopt and act on good ideas. But the Biden campaign gave Trump no quarter. They elevated every good idea they found as soon as they saw it. The result of this was that the Biden campaign put the implementation of several good ideas out of reach for the duration of the campaign.

When the president arrived at work on the morning of April 17, the case for a Pandemic Testing Board was on his desk, including specifics for a proposed organizational form. Conversations with Jared Kushner and Brett Giroir between then and April 25 indicated engagement with the testing question and knowledge about the untapped capacity in the country to scale up testing. Then on April 27, with the simultaneous release of the competing proposals on testing from the administration and the campaign, the engagement from the White House on testing ended.

The conversation had turned to vaccines, we were given to understand by associates of Kushner. The concept of executive office oversight of the supply chain was applied not to testing but to the work on vaccines. And indeed the policies that came next from the White House confirmed this. By April 27, the Department of Health and Human Services had already begun making major investments in vaccine discovery and production. They had already invested roughly half a billion dollars each in Johnson and Johnson (March 30) and Moderna (April 16). But then on April 29, the administration took the reins and announced Operation Warp Speed.[3] The operational structure set up by the White House to run Operation Warp Speed was very similar in structure to what we had recommended for the Pandemic Testing Board. Next Operation Warp Speed made an announcement on May 21 of a $1.2 billion investment in the Oxford-AstraZeneca collaboration, which was promising to deliver a vaccine in October. The White House thought they had found the ticket to winning the election.

As the press release put it: “Responding to President Trump’s call to develop 300 million doses of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine by January under Operation Warp Speed, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and AstraZeneca are collaborating to make available at least 300 million doses of a coronavirus vaccine called AZD1222, with the first doses delivered as early as October 2020.”[4]

Both a success at ramping up testing and contact tracing to levels sufficient to suppress COVID, and a vaccine delivered in October, were outcomes with the potential to win the election for Trump. From the outside, we interpreted the sudden shift of energy and effort from testing to vaccines as a bet being placed by the administration on which path would be the surest, simplest route to reelection. While testing might have delivered that too, the implementation challenges were going to require hard work and logistical mobilization on a wartime scale. Rapid vaccine development, in contrast, had all the glamour of a moonshot, and fewer near-term implementation headaches to worry about. All glory, no struggle.

The Democrats maintained the focus on testing and contact tracing, and even on some degree of supported isolation. The House of Representatives passed the HEROES Act on May 15, 2020, pushing further beyond the April 27 commitments of the Trump administration and the Biden campaign. But the House legislation also included proposals on a variety of other issue areas, most importantly election security. The House wanted to authorize funds to the states to support preparation of mail-in voting and ensure election integrity given other changes to the voting system that needed to be made in that pandemic year. From May 15 until the end of September, the Senate refused to move forward any compromise bill that included those election security provisions. Republicans believed that the Democrats were simply seeking investments that would increase turnout in their favor. Time was on their side. All they had to do to win the negotiation over investment in election security was to do nothing. Consequently, legislative commitment to a massive ramp-up of testing and contact tracing was not forthcoming, once more a casualty to questions of politics, and the contest over the upcoming election.

While the technocrats were not independently able to raise or address the larger strategic question of how we might suppress COVID while securing our economy, civil society actors did put that question on the table for elected officials. Members of both parties saw the importance of the strategic question and the value of the TTSI playbook. But at the end of the day, leaders of both parties prioritized questions of electoral advantage over implementation of TTSI. And we got the results that such a focus paved the way for. Viruses can be counted on to exploit every opening that allows them to spread, and the massive breach of our political divisions gave the novel coronavirus its opening to bring death, suffering, and economic disruption on a massive scale.

A broken social compact: Where We the People went wrong

Our polarization as a people is so severe that it disabled our elected officials in a moment when they should have been able to come together for decision-making in response to a crisis. But that polarization among us, which prevented widespread, full-throated advocacy for compromise, was not the only failure in our social compact to have undermined our the U.S. response to COVID.

Our second failure is that we have truly split into a society of haves and have-nots. Our commitment to public goods is so eroded that even in a crisis of the magnitude of the COVID pandemic, the default has been that private actors have taken care of themselves while others have gone without. The home institution of one of us, Harvard University, and the National Basketball Association created testing-based bubbles for themselves. Mission-driven imperatives to protect the organization and to model what was technically possible led to these private success stories. But at the same time, essential workers, teachers, and low-income families were going without. The contrast was painful to watch. The work of civil society actors need not have ended with modeling technical possibilities. There was a crying need to advocate for achieving the same infrastructure for all.

The privatization of the U.S. response to COVID was like responding to terrorism by encouraging every civil society organization to build its own private security corps. Those with resources are protected, everyone else is not. A blameworthy shrug of acceptance on the part of the comfortable sets our course in this direction. The tale of two countries that characterizes our national life — of the affluent and then everyone else — just got worse.

What’s the alternative? In fighting terrorism in the wake of 9/11, we built a broad public infrastructure of security — ranging from airport security checkpoints to new ways of monitoring public transportation to the ongoing work of people investigating specific threats and networks. We did see the growth of a certain amount of additional private security. One can’t enter high-rise buildings in New York City now without showing an ID. But the broad structures of public security mean that everybody is included in the umbrella of protection and uses of private security are minimized.

The national sports leagues, the nation’s colleges and universities, even the nation’s small business associations might have banded together to advocate for massive public investment in the ramp-up of testing and contact tracing that we needed in the spring of 2020, to provide a public good to which all needed access. But they did not. Instead, each organization built its own private COVID-suppression operation.

Implementation of testing, tracing, and supported isolation in the U.S. context faced at least three important challenges that made full-throated support from civil society imperative for success.

1. Because the disease had spread to a much larger share of the population in the U.S. by the time lockdowns began than in many of the most successful countries, the testing required to bring it under control was on a much larger scale than elsewhere. Combined with the sheer size of the country in both area and population, testing at the required scale required a large mobilization of resources.

2. Given the temporal distance from the last major pandemic affecting the country (with the exception of the qualitatively different case of AIDS), the U.S. had little cultural familiarity with the crucial process of contact tracing. Tracing infrastructure was limited, but more importantly there was a severe lack of trust between institutions capable of undertaking such tracing (whether primarily human-led or primarily digital) and the public. This made setting up a contact tracing infrastructure quickly and at scale difficult not just logistically but socially and politically.

3. The contentious history of public policies around social insurance and especially public health care in the U.S., as well as around civil liberties, made the most apparent pathways for supported isolation politically challenging. Social support-based inducements that are natural in a European context were less so in the U.S., while social or state monitoring-based measures employed in Asia clashed with American sensibilities. Similar issues compounded the challenges with contact tracing, given the sharp divide in the U.S. between aggregated and thus depersonalized public data efforts and the culture of distrust and privacy around individual health data. Since contact tracing required interpersonal but non-anonymous data, and more broadly disease surveillance required thoughtful integration of data across many often-competing social levels, the contentious fragmentation of the U.S. system made it difficult to execute on key tasks required for disease suppression.

In light of this backdrop, any chance of successful TTSI programs at scale required a full-court press by a range of institutions with social legitimacy across the diverse segments of American society to build support and understanding for the extraordinary measures necessary to avoid lockdowns, much as occurred in the mobilization for World War II. While the issues were somewhat more severe in the U.S., mobilizations like this occurred very effectively in countries like Taiwan, Estonia, South Korea, Germany, Austria, and Denmark and with some efficacy in much of Western Europe and Canada.

Such mobilization did occur in the U.S. later in the course of the pandemic on another issue. When the Trump administration promulgated very restrictive new immigration rules that would have forced the nation’s many international students to withdraw from their universities, the universities rallied and lobbied, and the rule was reversed in a matter of days. In other words, civil society did in fact have the power to impact administration policy around COVID.

But the nation’s sports leagues, universities, and small business associations never rallied to lobby for testing. With regard to universities, instincts are well and rightly honed to lobby on behalf of protection for immigrants. But their instinct to lobby on behalf of the American people as whole, especially in a time of crisis, needs renewal.

In the middle of June, our research network was still seeking to rally the administration and civil society to the cause of pursuing suppression of COVID through a TTSI strategy. We wrote to the leadership of the American Association of Universities seeking their support. We received the following response: “We reviewed and discussed your efforts on suppression strategy and it falls outside the scope of our issues and current legislative focus on COVID-19. We are keenly focused on seeking federal relief funds and targeted policies to alleviate the pandemic’s impacts on students, the ability of institutions to serve students, and research. …. While AAU will not weigh in at this time on a national suppression strategy, I would appreciate your keeping me informed of your efforts. We will monitor this issue going forward, and look for potential opportunities to be supportive in the context of our key legislative priorities.”

If our leading academic institutions could weigh in on the value of a national suppression strategy but chose instead to tend primarily to their own individualized organizational interests, we are blind. We have lost an understanding of a concept of the public good. One hopes that this loss is not beyond repair.

Conclusion: Lessons for the next pandemic

The urgency of telling this story has less to with understanding the disease that has now largely taken its deadly toll in our land, and more to do with the need to face the broader crisis confronting us today. The same countries that successfully suppressed COVID are coping better with nearly all major contemporary social problems: economic and regional inequality, job creation, climate change, digital monopolies, and disinformation. If we are to do better in these matters than we did in the test of 2020, we must have the humility to learn before it is too late.

For many years Americans have bemoaned government paralysis and social division, more as a pastime than an urgent cry. COVID-19 has made clear that our divided house is increasingly failing to stand. No constitutional democracy can meet and master urgent crises without civic strength — effective lines of communication and collaboration across disciplines, regions, social classes, racial, ethnic, and religion groups, and political positions. Solutions to our polarization exist.[5] But to fight our polarization, we have to avoid the same pitfalls that led to our failure in the fight against COVID. We must stop weakening our own capacity for decision-making and action through internal division. We must stop being so blinded by our internal hatreds that we cannot look curiously outwards to learn how to surmount them.

[1] A March 28, 2020, version of the relevant web page includes this language, at https://web.archive.org/web/20200328172009/https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html.

[2] C-SPAN, “Redfield on Masks,” https://www.c-span.org/video/?c4863997/user-clip-redfield-masks.

[3] Jim Acosta and Paul LeBlanc, “Trump administration launching operation to accelerate development of coronavirus vaccine,” CNN, April 29, 2020.

[4] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “COVID-19 Vaccines.”

[5] See Danielle Allen, Democracy in the Time of Coronavirus (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022).