Update (9/20/2022): The Rubio-Lee framework discussed in this analysis was recently released as legislative text by Sen. Rubio (R-Fla.) along with Rep. Alison Hinson (IA-01). This new release is substantively unchanged regarding the areas discussed in this analysis.

The Supreme Court’s recent ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson has sent abortion law back to the states, inspiring conservative interest in policies to support families bearing the costs of having and raising children. Following the decision, Senators Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) endorsed a package of policies that would increase support for families with children. Dubbed the “Providing for Life Act,” the framework includes paid leave and an expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC). The expanded CTC is of particular interest because it comes on the heels of another recent proposal to reform child benefits released by Senators Mitt Romney (R-Utah), Richard Burr (R-N.C.), and Steve Daines (R-Mont.). This plan, Family Security Act 2.0, is more favorable to households with lower incomes, married parents, and larger families. Despite Rubio’s CTC expansion framing as a “pro-life policy,” it largely misses its intended population due to how its benefits are limited to tax liability.

Rubio’s CTC expansion isn’t really a pro-life benefit

The following comparison focuses on each proposal’s main child benefit. The other elements of the proposals are not comparable because only Romney’s plan is currently deficit neutral. Both proposals increase the maximum child benefits above the CTC’s current value of $2,000. Romney proposes a maximum of $3,000 per child ages 6-17 and $4,200 per child under age six, while Rubio’s proposal provides a maximum of $3,500 per child ages 6-16 and $4,500 per child under age six.

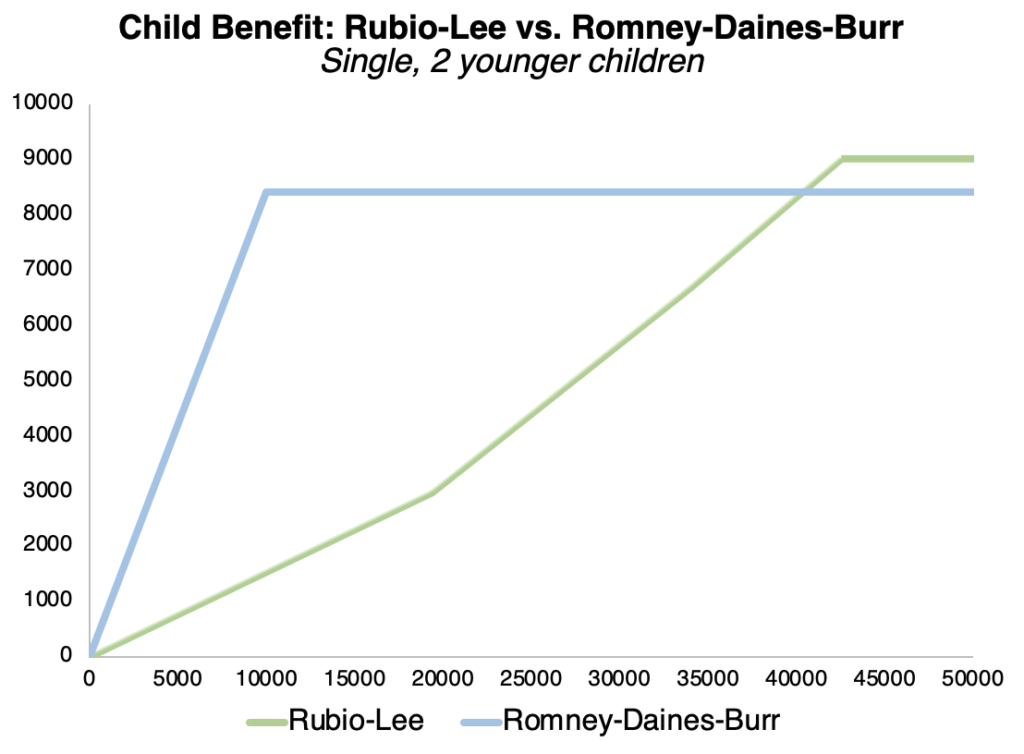

Yet these maximum credits hide crucial differences in how generous the Rubio and Romney plans would be for a typical family. Under Rubio’s proposal, total benefits could not exceed a household’s combined payroll and income tax liability. In contrast, Romney’s proposal rapidly phases in a household’s entire benefit by the time it reaches $10,000 in income. As a result, Rubio’s proposed child tax credit is much less generous to low- and middle-income households than Romney’s proposal, particularly for families with multiple and/or younger children.

For a “pro-life policy” to be anything other than empty lipservice, it must address cash constraints among low-income mothers. About half of women who have abortions live below the poverty line. To put this into perspective, the income poverty threshold for a household of two is $18,310. Yet, under the Rubio plan, a household with one young child would need to earn about $25,500 to receive the full value of the expanded CTC. Furthermore, mothers with previous children make up roughly sixty percent of abortion recipients. Households with multiple children must have an even higher income to receive the full child tax credit. Under Rubio’s plan, a parent with two younger children, for instance, would need to earn a bit over $42,500 in order to receive the full value of child credits they are eligible for. As a result of these facts, it’s safe to say that Rubio’s CTC expansion largely misses its intended population.

The Rubio proposal would, for example, do little for a 19-year-old woman with an unplanned pregnancy and limited work experience — the very sort of household most likely to be affected by Dobbs, as well as for whom financial support can be the deciding factor in whether to keep their child in states where abortion remains legal.

In the most recent high-quality survey, 73 percent of women who have had abortions identified “can’t afford a baby right now” as an important motivating factor. And previous evidence shows that providing cash assistance reduces abortions, including natural experiments based on Spain’s introduction of a child allowance and better child support enforcement in the United States.

While Romney’s proposal is markedly superior to Rubio’s at delivering assistance to cash-constrained households with women most likely to undergo an abortion, it also could be improved on this front. Removing the child benefit’s income phase-in entirely for infants and young children would be immensely helpful for families navigating the income disruptions and associated stresses common to the period surrounding the birth of a child.

Tapped out on Child Tax Credits

Rubio’s approach of pegging child benefits to tax liability has effectively run its course. Decades of tax-cutting, and the broader progressivity of the U.S. federal tax code, leaves most working-class parents with little remaining liability to offset through tax credits. Substantially boosting the per-child CTC without embracing a much faster phase-in rate entails that only families with high incomes will capture the full, per-child credit.

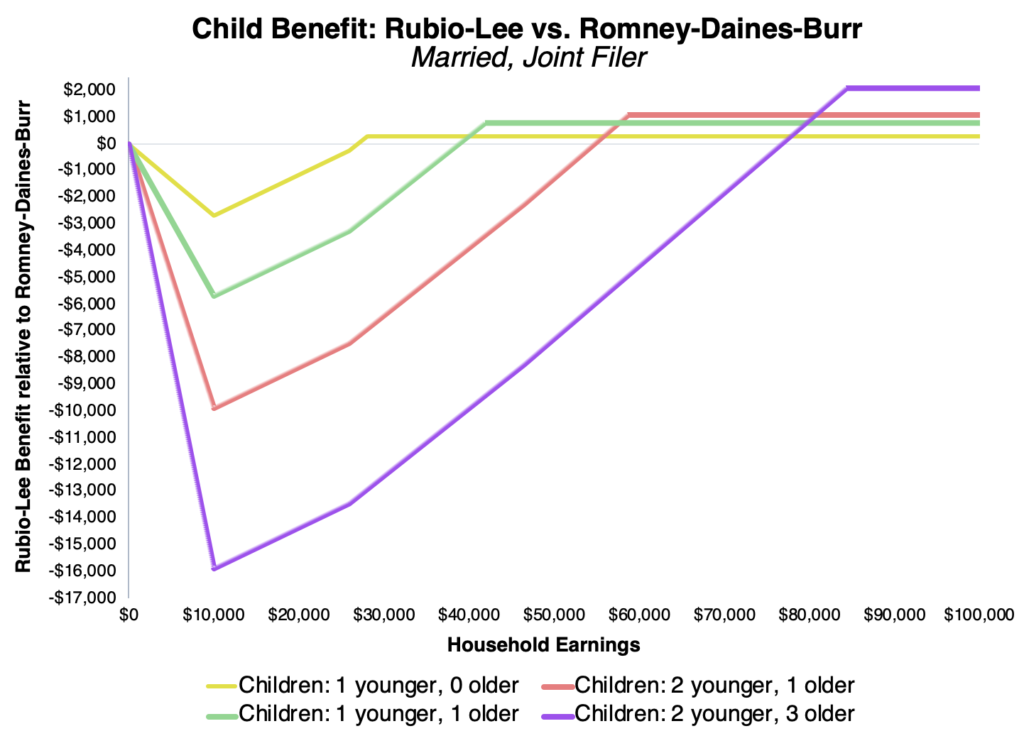

Directly comparing the Rubio CTC expansion with the child benefit proposed by Romney illustrates the problem. Under the Rubio proposal, larger families won’t be able to receive their full CTC until their income approaches or even surpasses the median household income.

The previous two GOP-led tax reforms in 2001 and 2017 invented and then built upon “payroll-tax refundability” as a kind of accounting fiction. Under this new framing, income tax liabilities were allowed to be negative by reference to the fact that workers also pay payroll taxes, limited to 15 percent of income in the Additional Child Tax Credit — proposed to be 15.3 percent under the Rubio plan to exactly match the combined employer and employee-side payroll tax. The inability to further expand the size of the credit for working-class families lays bare the problems with continuing to rely on tax liability as the ultimate constraint.

Tying benefits to tax-liability is especially problematic for married filers. Married households have a higher standard deduction and must have higher incomes to offset the proposed expanded child benefit. Romney’s plan overcomes this issue by fully phasing in benefits when incomes reach $10,000, regardless of total benefit eligibility or tax-filing status. Rather than exacerbate marriage penalties, Romney’s universal $10,000 threshold thus creates a significant marriage incentive for the lowest income parents. And that’s on top of the various other pro-marriage changes made under Romney’s framework.

The difference between Rubio and Romney’s treatment of married couples speaks to a deeper philosophical difference between the two proposals. Romney’s FSA 2.0 reflects the most serious effort to date at reducing disincentives to marriage across the universe of family benefit schemes. The Rubio plan — by insisting on being framed as a tax cut — would ironically make marriage penalties worse.

Finally, as mentioned previously, the bulk of revenue necessary to finance Rubio’s plan is currently unaccounted for, with a fact sheet noting only that eliminating the State and Local Tax Deduction (SALT) would be used to help pay for the proposal. Romney’s plan also proposes eliminating SALT, with the rest of the financing provided through consolidations of existing child-related expenditures including Head of Household filing status, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, and a portion of the Earned Income Tax Credit. For this reason, Rubio’s package could outperform Romney’s among certain groups of low-income parents if tax increases on higher-income households were used to pay for the remainder of the plan.

Conclusion

Romney’s child benefit is more favorable to households with lower incomes, married parents, and those with larger families than Rubio’s. The “tax cut” strategy for framing child benefit expansions has been successful in the past, but we should now recognize that it has effectively run its course. The tax liability constraint ultimately prevents Rubio’s plan from correctly functioning as a genuine “pro-life benefit”, failing to meaningfully provide assistance for women likely to pursue an abortion in the first place. Romney’s benefit design is much better suited to a post-Dobbs world, though it could also be improved here by providing the full benefit regardless of parental income for children in their infant years.

Photo Credit: iStock