Policymakers are looking for ways to break the stalemate over extending temporary enhancements to the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) that have now expired. Today, Republican Senators Mitt Romney, Richard Burr, and Steve Daines released a proposal that shows a possible way forward: the Family Security Act 2.0. It’s the latest iteration of a previous Romney proposal aimed at supporting families and simplifying an array of family-related tax benefits. This report provides a preliminary analysis of the reform package.

We find that the new Romney plan would reduce marriage penalties built into several existing family tax benefits and reduce child poverty by 12.6 percent. The proposal also reduces complexity in the tax code by reforming or consolidating five distinct tax benefits — the CTC, EITC, Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, Head of Household filing status, and State and Local Tax deduction — into just two: an enhanced child benefit and simplified EITC.

Net impact of reforms on families

The net impact of the Family Security Act 2.0 would be to lift over 1.1 million children out of poverty, a 12.6 percent reduction in the child poverty rate.

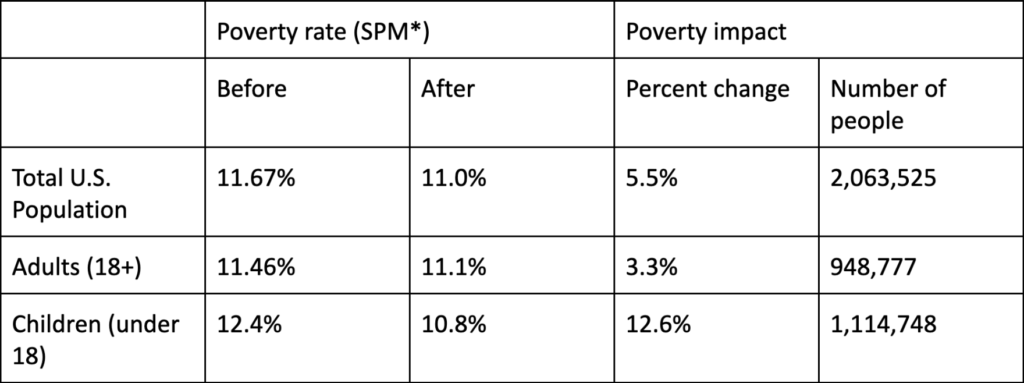

Table 1: Estimated poverty impact of Family Security Act 2.0

Reforming the Child Tax Credit

The Family Security Act 2.0 plan modifies the existing Child Tax Credit in five ways.

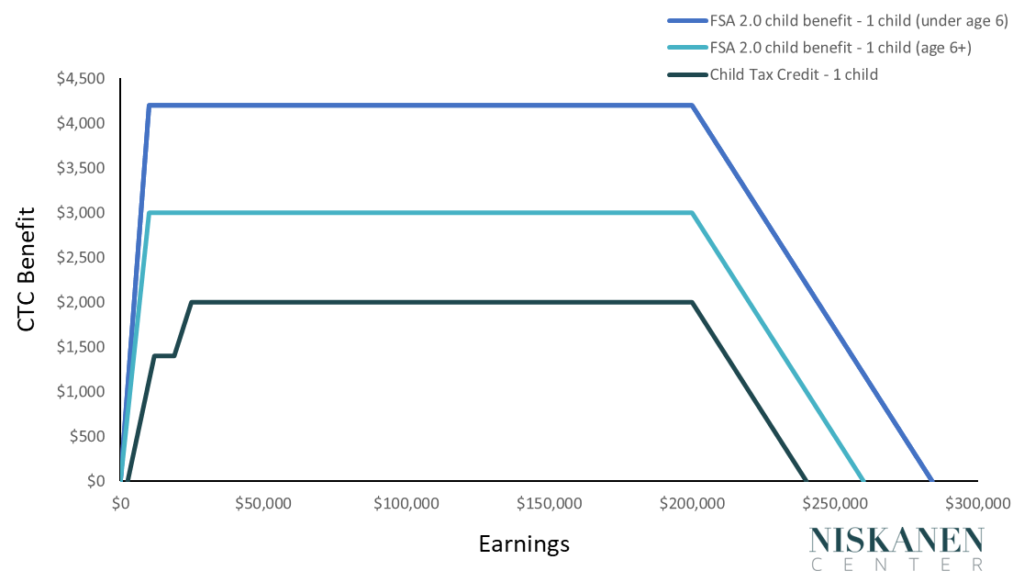

First, it increases the benefit, which varies by the age of the child. It boosts the current CTC, currently worth up to $2,000 per child under 17, to $3,000 per child ages 6-17, and to $4,200 per child under age six. Because parents of young children are earlier in their careers and face additional expenses related to pregnancy and child care, research suggests that extra support for families of young children is especially crucial to ensure appropriate child development. The benefit would then phase-out gradually for incomes above $200,000 for single filers and $400,000 for married filers in line with the CTC’s existing structure.

Figure 1: Current and proposed child benefit structure

Second, it shifts administration from the Internal Revenue Service to the Social Security Administration (SSA) and gives families the option to receive benefits on a monthly rather than annual basis. This has several potential advantages for ensuring timely and reliable delivery of child benefits to families. The change is possible because, while the existing CTC is based on current tax-year income and thus can only be claimed upon filing at year-end, the Family Security Act 2.0 plan bases eligibility on parents’ income the previous tax year.

Third, it expands the Social Security Number (SSN) requirement to parents. Under current law, noncitizen households with a Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) are eligible for the CTC as long as each child claimed has a valid SSN. Under the Family Security Act 2.0, families will be eligible to receive the child benefit so long as at least one parent possesses an SSN. Notably, this same standard would be applied to the plan’s reformed EITC as well, which currently requires both parents in a married couple to have SSNs.

Fourth, the plan substantially changes the current income requirements and phase-in rate for the CTC. Under the Family Security Act 2.0, households must earn $10,000 to receive the full benefit — far below current thresholds — and families can get the entire credit for up to six children. Below the $10,000 threshold, the benefit phases in proportionally with income. Meanwhile, the rate at which that proportional phase-in occurs varies with the maximum possible amount a family would get if they crossed the $10,000 earnings mark. That effectively quickens the phase-in for families with more or younger children. These changes result in a considerable expansion of benefits to working families whose wages are below the federal poverty line.

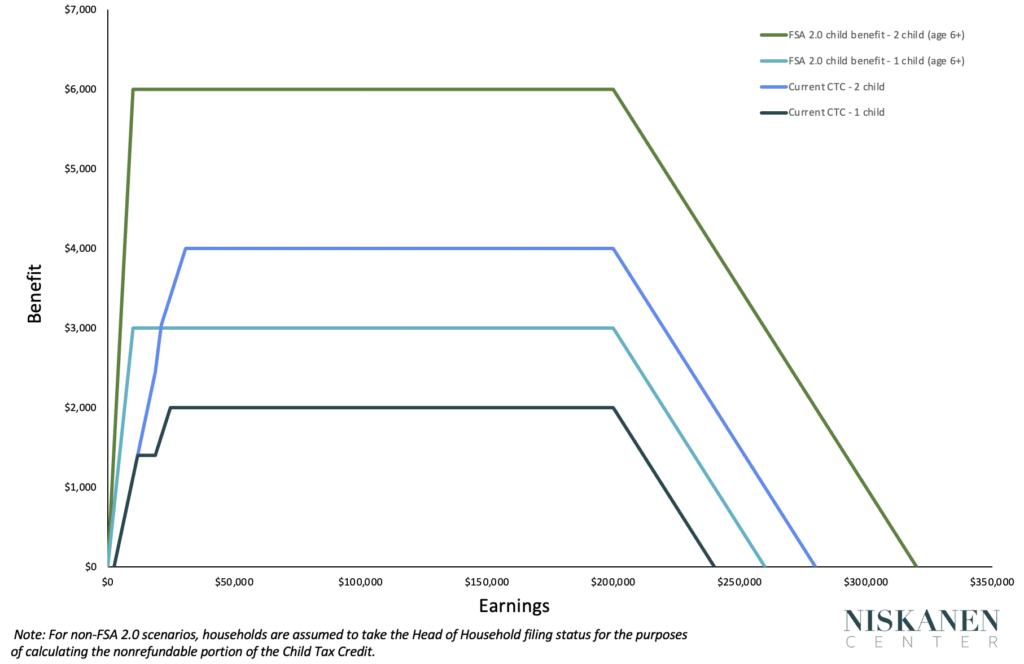

Figure 2: The Family Security Act’s dynamic income requirement

Figure 2 illustrates the impact on lower-income families. For example, family who earned $9,000 last year with two children (both aged six or older) would receive 90 percent of their maximum possible benefits — $5,400 total. In comparison, the current CTC phases in after $2,500 in earnings at a flat 15 percent up to $1,400 per child. The remaining $600 of the CTC are only available to be offset against taxes, excluding families who don’t earn enough to pay income tax. As a result, that same family with two children currently only receives about $975 at $9,000 of income, not drawing the full benefit until they have earned around $32,000.

Lastly, the plan makes families eligible to receive benefits earlier. Under the existing CTC, families must wait until the tax season following the birth or adoption of their child to claim the credit. The Family Security Act 2.0 allows parents to receive a portion of benefits beginning four months before the birth of their child. This change would provide expectant parents with additional resources to prepare for their child’s arrival, helping support prenatal health.

Reforming the Earned Income Tax Credit

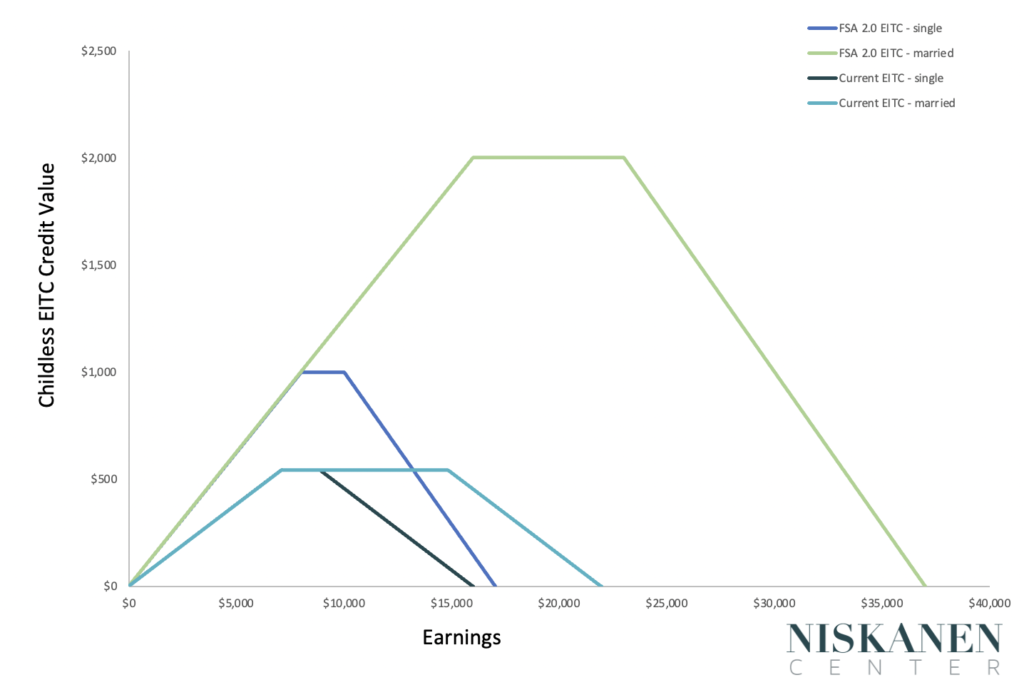

The Romney-Burr-Daines plan also undertakes a significant reconstruction of the EITC. The proposed changes come in three steps.

First, it shifts most child-related benefits from the EITC to the new child benefit discussed above. This change puts the United States more in line with best practices in other countries. For example, most countries typically have distinct child benefits, aimed at helping parents with the cost of raising children, and in-work benefits, aimed at ensuring low-wage households are better off working than receiving unemployment benefits.

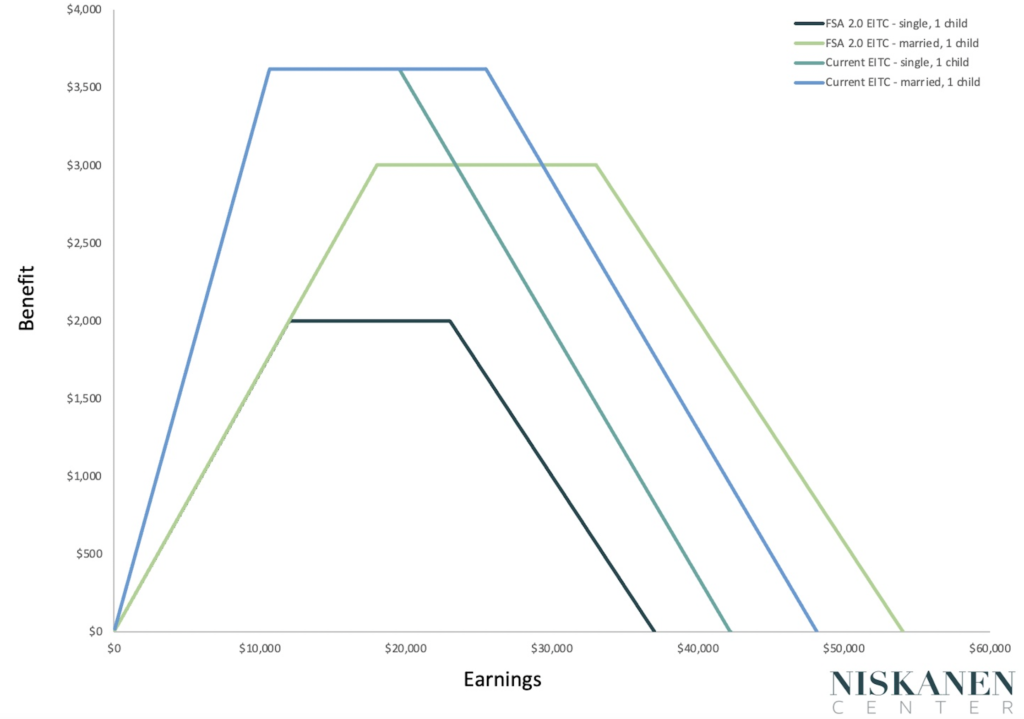

Second, it substantially reduces marriage penalties built into the existing EITC, the structure of which results in many working-class households losing benefits if a parent marries their partner. Marriage penalties in the tax code arise when the combined value of tax credits and deductions for two single individuals arbitrarily drops when those same individuals marry and file taxes jointly. Whereas other proposals effectively double marriage penalties in the EITC, the Family Security Act 2.0 reconfigures phase-in/out thresholds to reduce marriage penalties for childless couples and single-parent households.

Figure 3: Current and proposed EITC parameters (1 Child)

Lastly, it dramatically simplifies benefit amounts, and phase-in and phase-out rates based on income and family status. The existing EITC is plagued by high error rates, which studies show are driven by the complexity of the rules around claiming a child. The need to return overpayments or risk an IRS audit create large administrative burdens on families. The Family-Security Act 2.0 streamlines several components to reduce compliance costs and confusion.

Figure 4: Current and proposed EITC parameters (childless)

In short, under the Family Security Act, the portion of the EITC benefit that varies based on the number of children is rolled into the expanded child benefit, simplifying the earnings credit while roughly doubling the maximum EITC for childless adults.

Further simplifying the maze of family benefits

In addition to the consolidation discussed above, the Romney-Burr-Daines plan eliminates the Head of Household (HoH) filing status, Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC), and State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction and redirects their funds to the more generous child benefit replacing the CTC. This consolidation builds on CTC reforms included in the 2017 tax law, which shifted benefits down the income ladder by consolidating the relatively regressive dependent exemption into a larger CTC that reached more working-class families.

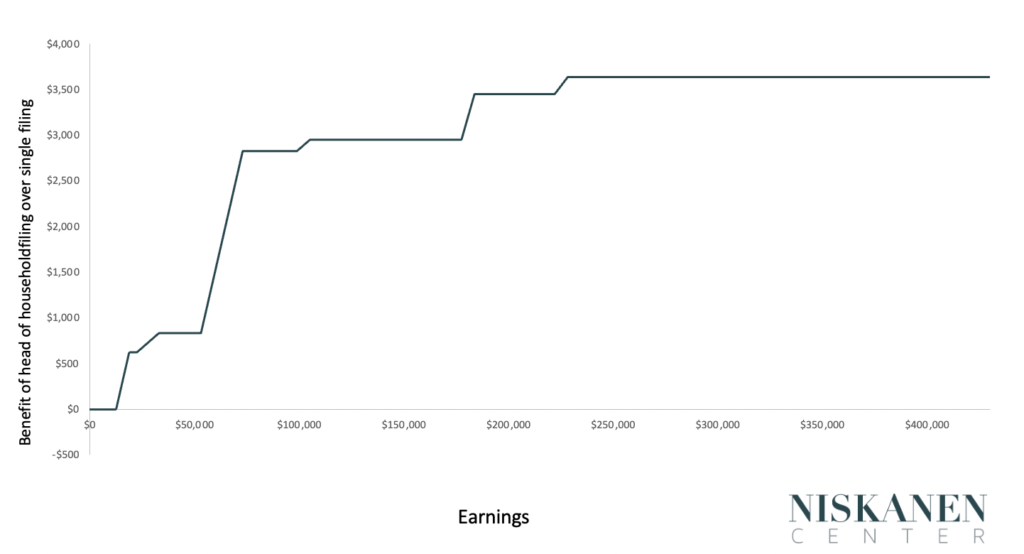

The HoH filing status provides a larger standard deduction to a single individual with at least one child than a single individual without one. Married couples receive no such bonus related to children. HoH filing status is the most regressive tool for delivering benefits to children in the federal tax code. As the figure below illustrates, it provides generous benefits to high-income households but little to no benefit for low-income households.

Figure 5: Head of household filing benefit (Individual income tax only)

The HoH filing status benefit is perhaps the most regressive source of marriage penalties in the U.S. tax code, delivering larger benefits as income increases not just on the personal income tax side but across other components of the tax code as well, including long-term capital gains. The Family Security Act 2.0 follows the British experience, where policymakers in 1998 eliminated a similar benefit limited to single parents by integrating it into an expanded child benefit available to all families.

Similarly, the CDCTC is a nonrefundable credit tied to paid child care, excluding the overwhelming majority of lower-income families, who tend to rely on family care arrangements or center-based care that is paid for with vouchers. Among the lowest-income quintile of households with children, only 0.2 percent claim it. Evidence also suggests that, among those able to claim it, much of the benefit is passed through to providers through higher child care prices.

Lastly, the SALT deduction allows itemizing households to deduct up to $10,000 in state and local taxes paid. It does not contribute to family economic security in any meaningful way. The vast majority of its benefits flow to the highest-income families.

Conclusion

Many members of Congress found themselves disappointed by the failure to come to a workable compromise on a permanent expansion of the child tax credit. The Romney-Burr-Daines plan offers an innovative way forward by addressing longstanding conservative concerns about the potential impact of our family security system on work, marriage, and poverty. It merits close consideration.

Joshua McCabe is the Niskanen Center’s senior family economic security analyst, and works on issues related to child poverty and household stability. McCabe previously worked as an Assistant Professor of Sociology and Assistant Dean for Social Sciences at Endicott College.

Robert Orr is a Niskanen Center social policy analyst who works on social insurance policy issues, health care, and labor market issues within the social policy team. He previously worked at the Cato Institute as a research associate, and as a graduate research fellow for the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.