In 2020, the fifth edition of the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) was released. It covers 56 of the world’s leading migrant-destination countries, assigning each a ranking across eight policy areas to determine an overall score regarding how well they integrate migrants. MIPEX describes itself as the “most comprehensive, reliable and used tool” to measure the integration policies of countries around the world.

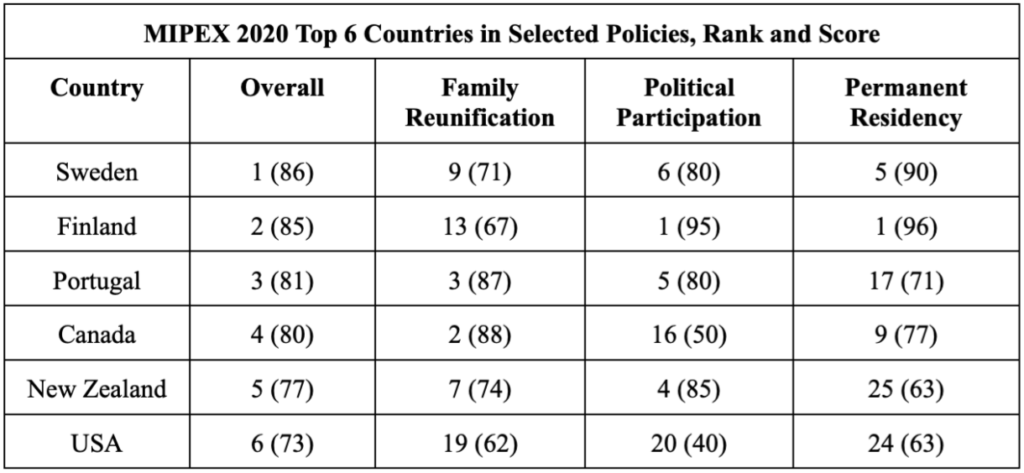

According to MIPEX, the U.S. ranks sixth overall, behind Sweden, Finland, Portugal, Canada, and New Zealand. Of the eight policy areas analyzed, the U.S. is competitive with the other five countries in five policy areas, but falls behind — in some cases drastically — in the remaining three: family reunification, political participation, and permanent residency.

So what are these countries doing differently?

Family reunification has purportedly served as the foundation of U.S. immigration policy since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. However, according to MIPEX, the U.S. ranks 19th in the world in this category, behind countries like Serbia, Indonesia, and Argentina. Four of the top five countries overall rank in the top-10 for family reunification, except Finland, which ranks 13th.

Canada, for example, ranks second in family reunification based on three distinct factors.

First is the sheer number of individuals granted permanent residency through family reunification channels. In 2021, Canada planned to make 103,500 family-based visas available. The U.S., on the other hand, has no limit on visas available to immediate family members — a spouse, child, or parent — of U.S. citizens, but has an annual cap of 226,000 visas available for all remaining family-sponsored preference categories. In fiscal year 2019, almost 710,000 family-based visas were issued. In 2020, the number dropped to fewer than 450,000. The U.S. annually issued nearly six times more family-based visas than Canada between 2018 and 2020, but it also has almost nine times the population relative to Canada. If the U.S. were to adopt Canada’s ratio of visas to national population, it would have to make closer to 900,000 family-based visas available each year.

Canada also gets high marks for managing its family-based visa backlog. As of February 2022, the family-based visa backlog stood at 102,222, with visa processing times around 12 months for spouses and 20 to 24 months for parents or grandparents. In the U.S., as of late 2021, more than 9 million people were stuck in the family-based visa backlog. This has led to wait times averaging over five years, and in some cases, over 20 years.

Finally, Canada has increasingly digitized its visa processing methods and has started to process applications remotely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. still primarily utilizes paper applications and the U.S. mail to process forms, and has been continuously stymied by the ongoing pandemic.

By far the most successful country in the world at immigrant political participation, according to MIPEX, is Finland. There are two major reasons for this.

In contrast to the U.S., Finland allows noncitizens to vote in municipal and county-level elections. To be eligible to vote, non-Finnish citizens must have lived continuously in the same municipality for at least two years prior to the election. As Finland is a member of the European Union, EU citizens have the additional right to participate in European elections. The only elections closed to non-Finnish citizens are parliamentary and presidential elections.

Another reason for strong Finnish immigrant political participation is the proactive role of the federal government in incorporating immigrants. In 2015, the Finnish government established the Advisory Board for Ethnic Relations (ETNO), designed to “enable dialogue between immigrants, ethnic minorities, authorities, political parties and civil society organisations.” The body provides a place where stakeholders can exchange ideas on topics like immigrant integration and political participation. While the recommendations ETNO issues are not legally binding, it still influences national legislation and decision-making.

The final area where the U.S. ranked comparatively worse than the other top-five overall countries was granting permanent residency, where it came in 24th. Reasons for this include high costs, tight eligibility requirements, and the limited rights permanent residents receive in the U.S.

Sweden (ranked 6th) does a noteworthy job at providing an easy and straightforward process for its immigrants to obtain permanent residency. There are two main reasons for this success.

One main difference between Sweden and the U.S. is the application process. In Sweden, a non-EU citizen not related to a Swedish citizen or permanent resident is in many cases eligible to apply for permanent residency after living in the country for five years with a residency permit. A complete application for permanent residency includes the following: a four-page application that must be completed in Swedish, copies of the individual’s passport, documentation showing how the individual is supporting themselves financially, and documentation of the individual’s accommodation costs.

In the U.S., the documentation required for permanent residency depends on the route the individual takes, usually either family- or employment-based. In most cases, two forms are required: the I-485 Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status and I-130 for individuals on the family-based permanent residency track or I-140 for individuals on the employment-based track. In reality, however, an individual applying for permanent residency in the U.S. will need to submit more than two forms. For example, the I-485 must be accompanied by up to nine additional forms, depending on the applicant’s situation.

Application costs are the second major difference between applying for permanent residency in Sweden and the U.S. In Sweden, it costs 2,000 krona (around $200) to apply for family-based permanent residency and 1,000 krona for non-family-based permanent residency.

In the U.S., the costs vary widely depending on the route one takes to obtain permanent residency and the forms to be submitted. For family-based permanent residency, it costs around $1,760 to submit a complete application. These costs include the I-485 and I-130 application fees and biometric data collection fees. The costs can be much larger for employment-based permanent residency, ranging from around $1,000 to almost $9,000. And these costs are independent of fees for an immigration attorney, which applicants find they increasingly need to succeed with an application.

While the costs and complexity of the permanent residency application process have been significant contributors to the U.S.’ low score on this metric, work has already been done to improve. For example, one of the reasons for the low score was the Trump administration’s August 2019 public charge rule, which made it easier to disqualify immigrants from obtaining permanent residency if they had accessed public benefits such as Medicaid and public housing. However, a federal court struck down the rule in 2020, and public charge reverted to its traditional, less strict definition. Changes to make the application process more straightforward and less costly would be a welcome start to making U.S. permanent residency readily available to those who qualify.

The MIPEX rankings make clear where the U.S. needs to improve in regard to immigrant integration. Other countries such as Canada, Finland, and Sweden provide successful examples of the kinds of policies that are useful and necessary for immigrant integration. However, not all needed policy reforms will be easy to implement.

Some reforms, like reducing application costs and creating forums to encourage dialogue between the federal government and immigrant communities, could be carried out solely through executive action. Others, like raising the yearly visa cap and discussing whether to allow noncitizens to vote will be more challenging. Although the forecast for these reforms is bleak in today’s political environment, they should represent aspirational goals for the U.S. to actively assist and encourage immigrant integration into American society.